By Gary Dretzka Dretzka@moviecitynews.com

Real Life Meets Cinema: Unmistaken Child and Throw Down Your Heart

Twenty-three years ago, in his Graceland album, Paul Simon anticipated the coming of the digital age and global shrinkage as well as any scientist, engineer or palm reader. It was an analog world back then, and Pope John Paul II, President Reagan and MTV Europe had yet to make a dent in the Iron Curtain.

Twenty-three years ago, in his Graceland album, Paul Simon anticipated the coming of the digital age and global shrinkage as well as any scientist, engineer or palm reader. It was an analog world back then, and Pope John Paul II, President Reagan and MTV Europe had yet to make a dent in the Iron Curtain.

“The Boy in the Bubble” not only envisioned a day when the free flow of music, images and ideas would help bring down the Berlin Wall, but it also foresaw a time when greedy media moguls would attempt to install toll booths on the superhighways of information and culture.

“These are the days of lasers in the jungle/Lasers in the jungle somewhere/Staccato signals of constant information/A loose affiliation of millionaires/And billionaires and baby/These are the days of miracle and wonder … And don’t cry baby, don’t cry/Don’t cry.”

Digital technology has made Earth a much smaller place. When the old Six Degrees of Separation game got too easy to play, the Internet crowd reduced it to Five Degrees, with or without Kevin Bacon.

And, yet, even today, there exist villages so remote – so insulated from the mass culture – they make Death Valley look like a thriving metropolis. There are musicians who wouldn’t know what to do with an electrical cord, even in the unlikely event someone extended the power grid to their community. Some religious movements identify their spiritual leaders the old-fashioned way, reading astrological charts, analyzing dreams, sifting through ashes and through meditation. We know places like this exist because some filmmakers have tired of playing God in the CGI universe and are finding wondrous people, places and things to document in places too difficult for most of us to reach.

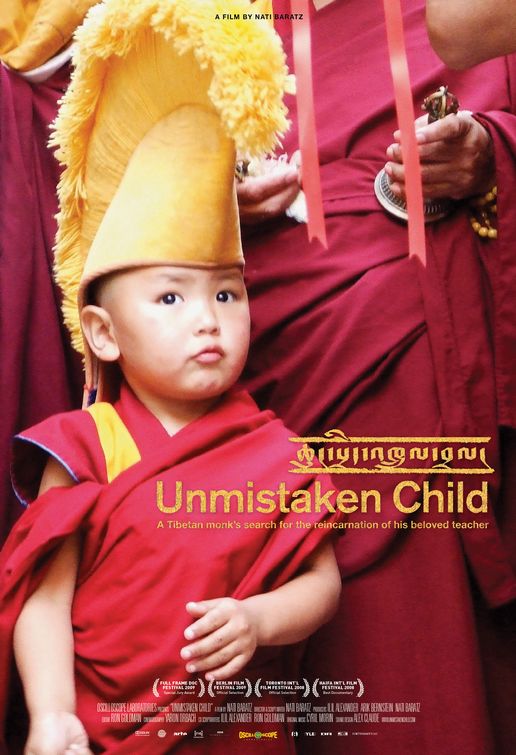

Two such films are Unmistaken Child and Throw Down Your Heart, and neither of them star Will Ferrell or require 3D glasses to enjoy.

For the illuminating Unmistaken Child, Israeli filmmaker Nati Baratz spent four years traveling through India, Nepal and a Tibetan valley so far off the beaten track China may not even know it’s there. He did so in the company of a Buddhist monk whose task it was to locate the one child among countless millions on the subcontinent who was the reincarnation of a greatly admired lama. The monk, Tenzin Zopa, had been taken under the wing of Lama Konchog at age 7 and remained his student, friend and colleague until his death in 2001. Who better, then, to identify the Master in a different body?

In Throw Down Your Heart, Sascha Paladino followed the American banjo virtuoso, Bela Fleck, around Mali, South Africa, Madagascar, Senegal, Gambia, Tanzania and Uganda in search of the progenitor of his chosen instrument. Along the way, the 11-time Grammy winner met musicians who worked wonders with the simplest of instruments. They made do with instruments whose sound derived from the proper combination of metal tines, wooden boards and sticks, goat skin, twine, wire and nylon strings. Some of the instruments – a marimba so long it required multiple percussionists and prehistoric-looking thumb pianos –might have been handed down from father to son for hundreds of years. Certainly the sound couldn’t have changed all that much.

“In Gambia and Mali, in particular, I found instruments and players that gave me a better sense of where the (banjo) thing started,” Fleck commented, in interviews reprinted on his website. “The three-string akonting (played in the movie by the Jatta Family troupe) could very well be the original banjo … everyone around Banjul certainly seems to think so. Huge numbers of slaves came from this area. …

“We were told that the musicians were allowed to play these instruments on the slave ships, and that many lives were saved due to it. … (In the movie), the banjo sheds its image as the quintessential American instrument to reveal a symbol of deep African heritage and the collective wail of the European slave trade.”

(The film’s title derives from an admonition given kidnapped Africans, before they were ordered to board slave ships heading to English colonies.)

Just as Ry Cooder was able to prolong the careers of the Cuban musicians featured in Buena Vista Social Club, Fleck has accorded the African players in the film even more exposure on a new CD and his “Africa Project” tour.

The movie that most resembles Unmistaken Child is Martin Scorsese’s Kundun, which dramatized the formative period in the life of the 14th and current Dalai Lama. Baratz’ film ends at the point where the chosen child is presented to other lamas (the wisest and most learned spiritual leaders) as the reincarnation of a man many of them knew very well. A screening test involving toys and objects that were favorites of the deceased monk is shown in both movies.

The access given Baratz throughout the process was remarkable. The closest comparison would be if a documentarian were allowed into the chambers where a new pope is chosen or invited into the delivery room to shoot the birth of a future king. In both Unmistaken Child and Kundun, however, it’s made perfectly clear that heredity and jawboning don’t count for much. The Dalai Lama either buys that the child is the reincarnation of a deceased spiritual leader – who, himself, had been reincarnated a lifetime earlier in another body — or he doesn’t, in which case, the search continues. (A negative ruling, here, would have made Baratz the proud owner of hundreds of hours of worthless footage.)

Lama Konchog was revered for his meditative prowess. Before he took on the 7-year-old Tenzin as a disciple, the monk had lived in a cave for 26 years, alone. Being assigned the task of finding his reincarnation may have been an honor, but, according to Baratz, “Tenzin only was frightened.”

The four years covered in Unmistaken Child, Baratz said, in a phone interview, from New York, “was a quest … a journey to maturity for Tenzin. He was scared, sure, but 10 minutes after entering that house, he said, ‘That’s the child.’

He’s become a leader and teacher, and he is responsible for the education of the boy.”

Baratz’ “obsession” with Tibet began in 1993, during a backpacking trek through the Chinese-controlled region. He had intended on making a documentary about a group of orthodox Jews who were looking for a hidden Jewish-Tibetan tribe. While in Nepal, he met Tenzin, who impressed him with his humor, faith and “especially huge heart.” Baratz felt the young man’s physical and emotional quest had mythical qualities.

During their time together in the field, Tenzin brought the filmmaker to the bare-boned hut – at the entrance of a different cave — he had shared with his Master, high on a mountain in the Tsum Valley. In all likelihood, the child for whom they were searching would be found in this highly spiritual region of the Ganesh Himal sub-range of the Himalayas. He would be around two years old and live near a village that began with an “ah” sound.

Even if the valley had electricity and phones, which it didn’t, a Google search would have proven far less fruitful to Tenzin and Boratz than being helicoptered in and walking from village to village, asking residents if they knew of any children of the right age. When Baratz needed to replenish the batteries of his equipment, he was required to turn to the solar charger positioned on the saddle of one of their horses.

“There was some concern about taking the helicopter into the valley,” Boratz recalled. “But, we simply landed in Nepal and walked into China. We weren’t so worried, then.

“A bigger problem would have come if the search had taken us to someone in the Master’s own family. They lived in a more accessible part of Tibet.”

Unlike Kundun, Unmistakable Child avoids discussion of the huge, long-standing schism between Chinese authorities and the Tibetan Buddhist community in exile and in Lahsa. After the Dalai Lama left the country in 1959, the secular government of the People’s Republic of China decided it would extend its authority to include the approval of reincarnations of high lamas. Following the 1989 death of the 10th Panchen Lama – the second-highest-ranking lama in the Gelugpa sect of Tibetan Buddhism – two boys were recognized as his reincarnation, one by China and the other by the Dalai Lama. In 1995, the 11th Panchen Lama, as decreed by the Dalai Lama, was taken into “protective custody” with his family, while the government’s Panchen Lama was chosen by a lottery system dating back to the Qing Dynasty.

The 14th Dalai Lama will turn 74 next month and the Chinese government has already said that the 15th will be born in Tibet and chosen according to its own dictates. For his part, the 14th Dalai Lama has already stated he will be re-born outside Tibet.

“This is logical,” he has asserted previously, when asked about his own spiritual and corporeal future. “The very purpose of a reincarnation is to continue the unfinished work of the previous incarnation. Thus, if the Tibetan situation still remains unsolved, I will be born in exile to continue my unfinished work.”

“Some people have complained about the lack of politics in the movie,” Baratz acknowledges. “That’s not what this movie was about, though. We wanted to get closer to the Tibetan culture and the belief in reincarnation.

“If you shout and make accusations, all you’re going to get in return is more shouting and accusations. I hope the audience will come away with something more contemplative.”

Baratz has been made aware of the Chinese government’s unhappiness in another way. He says Chinese authorities have convinced Japanese officials to dissuade distributors from buying the picture. Even though Japan has a large Buddhist population, “Unmistakable Child” won’t make a dime there, unless the pressure eases.

“The Dalai Lama appears in our movie and, even though he doesn’t say anything controversial, the Chinese consider it to be political,” Baratz said. “I haven’t been invited to show the movie and people are afraid to buy it.”

It’s likely that Japan doesn’t want to antagonize China, ahead of any debate about which 15th Dalai Lama will be the one recognized by its citizens. Too much is at stake economically to take sides in what many politicians consider to be a lose-lose situation.

“I was confronted by a representative of the Chinese government at the Krakow Film Festival,” he adds. “He was angry it was being shown and disputed the facts. But, outside of Japan, we haven’t had any distribution problems.”

The filmmaker was concerned, however, that some viewers will make a stink over rituals that could be considered abusive to the chosen child. On the day of the interview, a columnist in the New York Post made some facetious comments about a scene in which the boy cries while having his head shaved in anticipation of his installation at the monastery, and, again, when he’s separated from his family.

“It’s a great honor for the family,” Baratz concedes, “but it’s still a tough scene to watch, especially when he complains, ‘I won’t have any friends.’ There are other children in the monastery, but only those at the highest level spend time with each other.”

If all goes according to plan, however, the chosen child will need to get accustomed to solitude.

“Tenzin hopes the boy will be like his master and love to meditate,” he says. “It will be his choice, though.”

If, after his studies at the monastery are completed, the boy decides it’s time to find a cave to call his own, one suspects he’ll be unreachable by Twitter, Blackberry or e-mail for a long time. Neither is it likely he would agree to be anyone’s friend on Facebook. If nothing else, a couple dozen years of isolation from the outside world will prove that the reincarnated apple doesn’t fall far from the tree of eternal bliss.

– Gary Dretzka

June 10, 2009