By Leonard Klady Klady@moviecitynews.com

Guillaume Canet’s Series of Most Fortunate Events

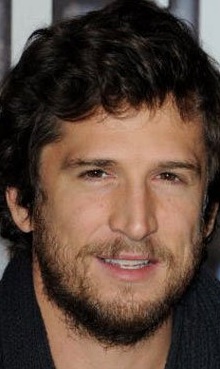

Considered one of the most versatile leading actors of contemporary French cinema, Guillaume Canet self-confesses that stardom –even the prospect of becoming a working performer — was a series of accidents.

Canet, 37, is ostensibly in Los Angeles for a few days to promote the film Farewell, a fact-based thriller about a French functionary in the Moscow Embassy who becomes a key player in a Cold War leak of Russian intelligence. His enthusiasm and guile belie his age and his animated style oddly compliments a rather endearing physical awkwardness. Without affect one readily sees why he’s earned a reputation on and off-screen as a heartthrob. “I made Super 8 movies as a boy,” he says. “And I just knew that someday I would make films. So I enrolled in acting school to learn about that process.”He also knew that he had to make ends meet while waiting for an opportunity to direct. And to his surprise work in both theater and television came more quickly to him than his more seriously inclined classmates.  Canet would spend a decade in front of the camera before he reached a level of acclaim that paved the way for a shot as actor-director and co-writer of Mon Idole, an acerbic look at office politics in the television industry.

Canet would spend a decade in front of the camera before he reached a level of acclaim that paved the way for a shot as actor-director and co-writer of Mon Idole, an acerbic look at office politics in the television industry.

At the start of his career he remembers going to see a play starring Jean-Paul Belmondo. At a certain point he recalls Belmondo’s character reading a letter and becoming upset. His stage wife asks him what’s wrong and he says “it’s nothing.” But when she presses him, he says “it’s from Canet … he wants to be an actor.”

“I was dumstruck,” Canet recalls. “I asked my friend, did you hear that?”

After the play an usher approached him and said M. Belmondo would like to meet you and took him to the actor’s dressing room. Backstage the joke was revealed. Canet, who was about to start his first film Barracuda, had told his co-star Jean Rochefort that he was going to the play. Rochefort called Belmondo and they engineered the “petite blague.” In retrospect he says it gave him his first sense of a community and that perhaps he might become a part of it.

His other credits as an actor have included Love Me If You Dare, Merry Christmas, L’Enfer, Espion(s) and The Beach with Leonardo Di Caprio. But to be honest, in America he’s better known by name than by visage. His second film behind the camera — Ne le dis a personne, aka Tell No One — became one of the biggest French box office successes of the past decade. It also won three Cesars — France’s top film award –including a personal triumph for direction.

“You know it was a big hit in France,” he demurs. “But I know that doesn’t mean it will work anywhere else. The (American) distributor asked me if I would come to America and I managed a few days between movies. There was really minimal press and they didn’t have a premiere screening. I thought well that’s nice and went home assuming not much would happen.”

The film, based on the novel by Harlan Coben, is a twisty thriller about a widower who begins to suspect his wife is alive. In the process of discovering the truth, dark, foreboding secrets are revealed. It opened theatrically in America in July 2008 to enthusiastic reviews and continued to expand the build commercial momentum through the summer and into the fall. Eventually it would gross $6.5 million in North America.

Canet recently completed filming (the week prior to this interview) his third feature as director, Les petits mouchoirs (Little White Lies), which he describes as “a bit like The Big Chill.” The ensemble piece (Francois Cluzet from Tell No One, Marion Cotillard, Jean Dujardin, etc.), like the earlier film, focuses on a group of friends about to take a vacation together when one of the band dies. They decide to go away anyway in honor of their friend and during the trip discover the self delusions of the title in both themselves and others.

The film is his first without a co-writer and that more than anything was a challenge. He also felt that promoting Farewell even for a few days would give him a little bit of distance before diving into editing and post-production. He’s been invited to screen in Toronto and knows it will be a mad drive to have it ready by September.

It becomes obvious quite quickly that he has enormous regard for writer-director Christian Carion, who made Farewell and Merry Christmas. He also adored co-star Emir Kusturica — better known as the director of such films as Underground and Time of the Gypsies — who he dubbed “The Bear.”

“He’s (Kusturica) totally organic; very charismatic and not at all psychological in the way he works,” says Canet. “There’s a scene toward the end of the film where his character realizes everything is lost and he’s supposed to break down. Before the shot he went up to Christian and said ‘I’m very sorry but I’m not going to cry in the scene’ and Christian was obviously very disappointed. Then the cameras rolled and at just the right moment Emir welled up and bawled — he had the entire set in tears. He’s just so touching as a performer.”

Ironically, Kusturica was a last minute replacement for a Russian actor who was set. In an odd twist of fate, that performer gave the script to a friend to translate and by coincidence the latter’s boss happened to be one of the Russian diplomats portrayed in the film. Suddenly the actor was out as were pre-approved Russian locations. Carion had a vague acquaintance with Kusturica (who lives in Paris) and, having nothing to lose, sent him the script. They also quickly relocated to the Ukraine.

He says that what drew him to the material was the prospect that anyone, given the right circumstances, could be a spy. It isn’t Bond or Bourne but people with families. And by the nature of the work you wind up lying to the people you love and it twists you into a pretzel.

Canet makes a joke that Carion’s bravery is typified by casting two directors in the film’s leading roles. But he’s quick to add that when he’s acting he’s not second guessing a filmmaker.

“I really love acting,” he says. “It’s very intense and then you leave. But while you’re doing it, when things are good, there’s so much freedom. You believe you can do anything and that’s very liberating. I know it will be time to stop when I lose that joy and start to look at my performance like a director.”

July 25 , 2010