By Mike Wilmington Wilmington@moviecitynews.com

Wilmington on Movies: Nanny McPhee Returns, Mao’s Last Dancer, Eat Pray Love and Lottery Ticket

Nanny McPhee Returns (Three Stars)

Nanny McPhee Returns (Three Stars)

U.S.; Susanna White, 2010

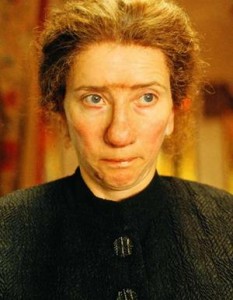

I love Emma Thompson, even snaggle-toothed and warty. And this Thompson-written, Thompson-starring way-beyond-Mary-Poppins WW2-era film of the Matilda books of Christianna Brand — who also wrote that wonderful WW2-set thriller Green for Danger (which became one of Alistair Sim‘s finest hours) — is a little loud, but pretty sunny, pretty chipper, pretty good.

Maggie Gyllenhaal, as Mommy Green, and Rhys Ifans as Phil’s-your-uncle Green-for-Danger, are snappy. (There’s that word again). Eros Vlahos, as Cyril, may grow into a silly, sunny British snob to match any Monty Python or even Hugh Grant. Ralph Fiennes is getting typed as the cloud that covers the sun; he should try a part as Sunny Smiles, the Banjo Man. (“We’ll meet again, don’t know where, don’t know when…“) Great little flying piggies in this movie. Miss Topsey and Miss Turvey, I’m sorry, take a hike.

Nanny is not really supercallifragilist-whatever. But sweet Emma rocks.

_________________________________________

Mao’s Last Dancer (Three Stars)

U.S.; Bruce Beresford, 2010

Ballet, that grand art of music and the body married together, is a natural subject for the movies — a potentially wondrous one, as The Red Shoes is there to prove again and again. And Bruce Beresford‘s fact-based drama Mao’s Last Dancer is an exhilarating example of a contemporary ballet film, fusing dance and drama, art and politics, body and soul: a real-life story, scripted by writer Jan Sardi (of Shine) from the experiences, and the autobiographical book, by Chinese star ballet dancer Li Cunxin.

It’s not a musical movie where the dance dominates. The movie works less from the music than from the ways Beresford and Sardi reveal the world around the dancers. But that’s not a drawback. It’s a fascinating world, and a fascinating story, about a complex person, who also happens to be a dancer — and who was able to escape into a new world because of it.

Li was a sensitive country boy from the mountains of China, who grew up with a poor but loving family (the great Joan Chen plays his mother, Niang) during the period of the Red Guards, the Cultural revolution, The Gang of Four, and Mao’s last roar. Amid this turbulence, a schoolteacher spotted Li’s natural gifts and got him picked to go to Beijing for study in ballet — as a time when furious political opinions raged in China about everything, including what kind of ballet to perform.

Supple and poetic, the boy Li (played by Chengwu Cuo and later by Wen Bin Huang) was a natural for the graceful, classical, Russian ballet matinee idol style of the Baryshnikovs and the Nureyevs. But, in the contentious and violent Vietnam and post-Vietnam era, everything became political, even a pas de deux. The aggressively radicalized “new dance” and “new art” proponents — in some ways, they remind me of the “film theory” proponents in cinema studies — saw those Russian defectors as traitors, and art as a tool of the state. They preferred blatantly political and pro-war subjects and simplistic, over-athletic styles. One of Li’s most sympathetic teachers is fired and exiled; he himself is bullied and tongue-lashed.

But the boy Li has a heart of oak and a firebird in his soul, as well as legs of spring and steel. He perseveres, practices and exercises obsessively, builds himself up. And when an American ballet impresario and director, Ben Stevenson (Bruce Greenwood) of the Houston Ballet, travels to China, on a cultural exchange program, bringing with him attractive young dancers of Li’s age from Houston, Ben spots Li’s rare gift — just as that mountain village schoolteacher could and did. He invites the now 18-year-old Li (played by Chi Cao for the rest of the movie) to come to America.

The more liberal Chinese diplomats agree and Li, the country boy plucked from obscurity to Beijing, now travels to America. There, in the rip-roaring 20th century New West, Li, who catches on fast, sharpens his English, is dazzled by shopping malls and dance clubs, and has a love affair with piquant fellow dancer Elizabeth Mackey (Amanda Schull). Li also steps in, at the last minute, to dance the role of Don Quixote in the Ludwig Minkus ballet (a staple of Nureyev’s repertoire) and to become a local star. When the time has come to leave, the determined teenager decides to marry Elizabeth and stay, and the hitherto tolerant Chinese embassy officials turn stony and imprison him in the embassy. A legal battle commences, with the story turning international and Li and his friends hiring a shrewd Houston attorney, Charles Foster (Kyle MacLachlan).

It is that story — of a poor boy, his spectacular rise, and the political storm he inspires — that dominates the movie, rather than the dance scenes, however spectacularly well they’re choreographed by Graeme Murphy and Janet Vernon of the Sydney (Australia) Ballet, and however well danced by Chi. This isn’t a Red Shoes-like fable to make your heart leap and your imagination soar. It’s a hard-edged story about how ideology and politics affect art, and of how art may triumph over ideology. (When Chi defects, his peasant parents suffer for it, become targets of the hard-liners.) The movie, which is as unsentimental, real yet compassionate as writer Sardi‘s Shine was, feels free to avoid “hero-izing” or romanticizing Chi, and to reveal his less attractive, more selfish and opportunistic sides.

In fact, for a good part of the movie, mostly after he grew up, I didn’t like him much at all, didn’t like the way he left his parents twisting in the wind, didn’t like the way he slid so easily from one patron to another, didn’t like the way he shed his first wife for a second. I wasn’t at all surprised to learn that the real-life Chi finally left the arts altogether — after dancing before a TV audience of 500 million with the Houston Ballet — to wind up as a senior stockbroker, of all things, in Sydney. (Dancing with the derivatives?)

A strength of the movie is that it shows us all that, without glossing it over. (Admirably, Chi lets himself be part of his own unveiling.) You don’t have to be a good person to be a great artist or dancer — and you don’t even have to be a good (or great) person to help affect profound social change or become a key social witness. You simply have to be there, be honest.

SPOILER ALERT

Still, the one moment that finally made me cry a little in this movie was the scene where Chi’s parents, after suffering so much, came to see their son dance in Washington, and proudly join him on stage. My eyes are dry for the dancer though, even as my hands applaud his art.

END OF SPOILER

Bruce Beresford is a good liberal director, who makes good liberal movies — including the lacerating Australian courtroom drama Breaker Morant, the brilliant lower depths country-western Tender Mercies, the touching anti-racist Southern tale Driving Miss Daisy, the harsh revisionist Quebec-set Western Black Robe, and his fine adaptation of Joyce Cary’s African-set Mister Johnson — though sometimes he gets knocked on the radical-chic meter for it. Yet Beresford uses good, thoughtful scripts (when he can) and he executes them truly well. He’s solid as a rock, and this is one of his best.

Here, with an expertise that seems effortless, director Beresford and writer Sardi not only plumb the contradictions of Li’s defection, they present what seems a notably gay character, Greenwood’s Ben (the type of role usually described in reviews as “flamboyant”) without making a fuss over it, or using him for a moral. They draw and contrast, with great economy, the social-political mores and changes in provincial China (Shandong province), the travails of dictatorship and the intoxicating release of democracy. They portray pungently the dueling rituals of the Beijing dance academy, and the contrasts of the inwardly rough and tough, pseudo-swank-elegant Houston society. And they swiftly and convincingly chronicle the sometimes liberal, sometimes hard-line shifts in the Chinese embassy, as well as the courtroom finagling Foster has to pursue to get Li free.

The movie does a lot. The cinematography, much of it on location, is by Peter James, who also shot Driving Miss Daisy, Mister Johnson and Black Robe for Beresford, and his work here is tough and elegant too. The actors, especially Chen, Greenwood, MacLachlan, and Jack Thompson — who was the fighting lawyer of Breaker Morant, and here plays wily Judge Woodrow Seals — are good as they can be.

I can’t promise your heart will soar after watching Mao‘s Last Dancer. Mine — embittered, a bit ravaged, a bit skeptical — certainly didn’t. But I think this movie, at its best, will help you appreciate how important are good teachers and brave good parents, smart lawyers, and cultural bridges. And how indispensable to us all are art and true freedom: not those bellicose Tea Party clichés, but the genuine article.

_________________________________________

Eat Pray Love (Two-and-a-Half Stars)

U.S.; Ryan Murphy, 2010

This movie — taken from Elizabeth Gilbert’s international bestseller about a year spent recuperating from a failed marriage and love affair, reaching nirvana through travel, romance, epicurean feasting and spiritual questing, communing with various great souls (who mix visionary searching with snappy patter) — is so beautifully shot, on such gorgeous locations (Rome, India, Bali), with such a superfine cast (Julia Roberts, Javier Bardem, Richard Jenkins, James Franco, Viola Davis, Billy Crudup), that for a long while, it seems better than it really is. But it isn’t. In the end, I felt gypped, manipulated, chivvied, jived. Ain’t no way to the Truth.

For one thing, there’s no explanation (at least none I remember) about how our Lizzie can afford to just go off and play and eat and meditate and screw for a year. That’s an itinerary I associate with bored or heart-smashed rich kids trying to find themselves, somewhere, anywhere.

You have to go to the book to find out that Gilbert got an (apparently very big) advance from her publisher specifically to write this book, with four months allotted for each country. (How about another half year devoted to drugs, Amsterdam and film noir?) Much of this adventure was all mapped out in advance — four months for Rome and food, four months for India and prayer, four months for Bali and whoopee. It’s all on the itinerary except perhaps for the climactic fling with Bardem as Felipe the boatman with the sleepy smile, with full charm intact and without Bardem’s No Country for Old Men Ish Kabibble-on-steroids horror haircut.

Better than this movie, I think, would have been a romantic comedy in which writer Liz sets up the whole spiritual-epicurean world cruise with her publisher, and then everything goes wrong, except at the end. But I guess life intervened, love intervened, the Great Soul flew down and blew smoke in our eyes.

Close your eyes. Breathe. Follow the light. Eat. Pray. Love. Prayer. Advance. Bank transfer. Prayer. Advance. Bank transfer. We should all have such a publisher! Then we wouldn’t need a spiritual guide, or God in any of his New York Times Bestseller List manifestations. Or margherita pizzas. Or snappy Yoda jokes. Or glycerin tears for the crying scenes. (Glenn Beck isn’t the only dry-eyed cryer around.) Or Felipe the fisherman, as long as he keeps Bardem’s new barber. Or Julia Roberts. No, strike that. We‘ll always need Julia Roberts. We’ll just sacrifice the apartment in New York, and a little angel hair pasta, and a guru or two. Love. Pray. Eat.

_________________________________________

Lottery Ticket (Two Stars)

U.S.; Erik White, 2010

One of my best newspaper buddies used to say about colleagues we knew who’d gotten great jobs or notable career advancement without really deserving them; “They won the lottery!“

Yeah. Yeah. I always knew what he meant. Winning the lottery is a surefire way of getting ahead in the world without displaying a lick of talent or hard work.

That‘s why, on one level, it’s a favorite fantasy of lots of the citizenry — and also why its hard to sympathize too much with ex-kid rapper Bow Wow as Kevin Carson, the protagonist of the new comedy Lottery Ticket. Kevin is a likeable guy from the Atlanta projects who suddenly wins 370 million dollars in the “Mondo Millions” super-sweepstakes — though he doesn’t believe in lotteries and thinks they’re a sham rigged to dupe poor people — because he bought a ticket with numbers he got off a fortune cookie. And because the numbers hit.

One hitch. It’s Saturday of a 4th of July Weekend that will stretch through Monday, so Kevin can’t cash the ticket until Tuesday the 5th. He tries to keep it a secret, but unfortunately, the other person who knows is his terminally talkative Grandma (Loretta Devine).

Soon, Kevin’s life has taken a marked turn for the worse, or at least the more dangerous. All of a sudden, he has all kinds of “friends” he doesn’t want — and his real longtime friends (including Brandon T. Jackson as best bud Benny, and Naturi Naughton as true blue gal pal Stacie — are feeling neglected. Terairra Mari as foxy Nikki, who wouldn’t give him a tumble, appoints Kevin her newest cutie. Projects smart-aleck David (Charlie Murphy) keeps pulling out his pistol to support him, a rod that looks suspiciously like a squirt-gun.

The local pastor, slick Rev.Taylor, preaches a sermon about a new multi-million dollar church building project and it’s aimed straight at Kevin‘s pew. The local Godfather and loan shark, Sweet Tee (the always excellent Keith David), is happy to float Kevin a $100,000 loan and leave him with a torpedo named Jimmy the Driver (Terry Crews), packing real heat, to look after his interests.

And the most dangerous man in the projects — psycho ex-con Lorenzo (Gbenga Akinnagbe) — wants the ticket, the 370 million, and maybe Kevin’s bootie, and doesn’t care whom he has to bash to get it.

We forgot one guy: Mr. Washington (Ice Cube), is an agoraphobic ex-boxer who hasn’t left his apartment in decades, who’s befriended Kevin (from whom he gets his groceries and necessities), and doesn’t seem to want anything from him. But Mr. W., who sparred with Ali and Ken Norton, is sure to figure prominently in whatever happens — and only partially because Cube is also one of the producers of Lottery Ticket.

Lottery Ticket has a terrific ensemble cast, and first time feature director Erik White (who worked on the script with scenarist Abdul Williams) keeps them all in high gear. The performances are lively, snappy (see Eat Pray Love), and sometimes as rich as Kevin will be, if he survives to Tuesday.

The script, unfortunately, falls apart by Sunday.

Why does Lorenzo, who’s out of jail on probation, shake down Kevin at his shoe store in front of his boss, and steal the ticket in front of dozens of witnesses? Why does foxy Nikki give up on her rich hubby campaign so fast? Why does Kevin just wander around everywhere with the still unsigned ticket in his pocket? By the way, aren’t there any cops in these projects? (We’ll concede law-enforcement problems may be worse than we know.) Why is Kevin so dense about Stacie? Why does David actually fire off his squirt gun?

And a troubling point, why does Kevin’s Grandma’s apartment, if admittedly a little garish, actually look larger and more expensive, than most of the apartments my own mother lived in for most of her life? Wouldn’t we have felt more sympathy for Kevin and his grandmother if the art direction for their place had been a mite less colorful, a little less lush?

Lottery Ticket is fun at times, and the cast is good, especially David, Murphy, and Faheem Najm as the convenience store guy who sells Kevin the ticket. And Williams and White do figure out a way to keep their Lottery Ticket from being, in the end, a paean to dumb luck and greed.

But the movie doesn’t hold up too well next to, say, that beguiling 1994 Nicolas Cage-Bridget Fonda Andrew Bergman-directed lottery ticket show, It Could Happen to You. And neither of them can match, or come close to, Christmas in July, Preston Sturges’ wonderful 1940 comedy where Dick Powell supposedly wins a big radio coffee jingle contest with the slogan “If you can’t sleep at night, it isn’t the coffee, it’s the bunk.”

Remember, if you can write great, you don’t need to win the lottery. Or so we like to think.