By Ray Pride Pride@moviecitynews.com

Interview: In Arm’s Way With Danny Boyle

In 127 Hours, Danny Boyle doesn’t present Aron Ralston as any kind of idealist of the great outdoors, or as a man surmounting the wilderness. Rather, the climbing enthusiast who was trapped for days in a Utah canyon by a fallen boulder is a blithe young man who may have reached the limits of his capacity for invention. There’s powerful imagery involving women and water in his follow-up to Slumdog Millionaire (written with Simon Beaufoy) but it’s James Franco’s portrayal of Ralston as he moves toward the choices he must make in order to survive that carry the film. Ralston’s not a literary stoic like James Salter, who wrote in his 1979 mountain-climbing novel “Solo Faces,” “There is something greater than the life of the cities, greater than money and possessions; there is a manhood that can never be taken away. For this, one gives everything.” Comparatively, Ralston’s just a kid with a dull pocketknife. But he does find what he must give in order to live to tell the tale. Boyle and I talk below about music, sound design, Sigur Rós, why a documentary of this material wouldn’t work, James Franco’s canniness, Sisyphus, John Ford landscapes, hallucinations, Scooby Doo, why Boyle used two directors of photography, using numbers in movie titles and how he’s been obsessed with stories from a confined point-of-view since before he became a filmmaker. We both talk fast and often overlap; we discuss pivotal plot points and other story elements. His laughter is generous and infectious, and there was a lot more of it than indicated. While edited, I wanted to preserve some of Boyle’s headlong speaking rhythm as much as possible. We spoke October 14, 2010 at the Elysian Hotel, Chicago.

PRIDE: You haven’t let up on your music and sound design. You evoke what Aron’s memory is doing to him that way, and it’s powerful, music, its hold over us. If you get it wrong, it’s abject. When you just get it right, sound and music, it bores into the brain, whereas we classify visuals in a literal fashion—

BOYLE: Yeah—

PRIDE: But music and sound design… whoosh.

BOYLE: I was just telling these three, I think they’re students, I was telling them, about seventy percent of a movie is sound. Seventy percent! It’s always thought of as a visual medium, and it is, of course, but it’s not.

PRIDE: It’s why 16mm optical failed as an exhibition medium, crap sound.

BOYLE: Crap sound. Yeh. Yeh. The first movie we made, when we made Shallow Grave, we had this discussion, because we had a million pounds and we were all just working out how to spend it. I said to them, we talked about, why was it, when were looking at movies in Britain, the British movies looked shit, and the American movies looked great, even if they weren’t great movies, they looked great. Why is it? And it was sound. American movies know you spend money on sound. Just because you can’t see it doesn’t mean you shouldn’t spend money on it. We ring-fenced money for Shallow Grave, proper money. Because we ran out of money, of course, for everything else. But we didn’t spend the sound money. And that was one of the reasons the film was a success and looked like it supposedly revitalized the British film industry. It’s only because we spent a lot of money on sound! [laughs] We dealt with it properly rather than threw it away, y’know.

PRIDE: Then you use one specific passage of music at the end that’s a rush. Sigur Rós, you can basically lay it on top of anything. You just feel great—

BOYLE: It’s wonderful. It’s wonderful. I don’t think you can put it on top of anything—

PRIDE: The piece you use—

BOYLE: “Festivale—”

PRIDE: “Festivale,” four different filmmakers could use it similarly for a climactic moment— [Boyle chuckles] And if it’s decent work, it would still soar.

BOYLE: It’s a beautiful piece of music, yeah, they do do wonderful music. I used their music in the temp score of Slumdog Millionaire. And then we replaced with A. R. Rahman’s score, we replaced it completely. And it was just temp… And then I gave it to the marketing department, and they used it, Hippopolia, Hippopopobolia, [“Hoppípolla”] whatever it’s called, that song, and they used it in the adverts for Slumdog, the nationwide advertising campaign they used it in which helped the film a lot. So when we came to this one, I wanted a song that took you through to the ending and celebrated people, really. ‘Cos the other thing about the Sigur Rós, which is weird about their stuff, is that it had a kind of life spirit in it that celebrates people, somehow, I don’t know quite what it is, and anyway, it fitted. It was so wonderful. And we spoke to them, because they don’t, they don’t license stuff without seeing how it’s being used, and they came in and watched the movie and… Yeah, they were very pleased. So yeah… it was good.

PRIDE: You don’t need to understand the lyrics, even when they’re singing Icelandic as opposed to the one album that was gibberish— [Boyle laughs agreeably] It still, it just soars… it’s rooted in the Icelandic music traditions if you hear their choral music or their classical music, pop music, but theirs, it’s just, “Hey, I’m a spiritual goofball.”

BOYLE: I know, I know, I know. I love that stuff.

PRIDE: How did Rahman’s score work on this film, it’s vital, it’s surging, there’s “world music” to it, but they’re not readily classifiable rhythms.

BOYLE: He was delighted to do it, because his problem—not problems technically or talent-wise—but his problem is obviously that he’ll be pigeonholed in the West as an exotic composer, at best, if not just purely an Indian composer. Where in fact his talent is completely universal… and extraordinary. On this, we started with solo guitar. He started working with this guitar player, a session musician from L. A., a solo guitar player, very, very good one. And so all the music you hear in it, even though some of it isn’t played on guitar, it all began on guitar, on solo guitar. And bluegrass. So that was the starting point for him. And that’s typical for him, he approaches it thoughtfully like that, tunes just pour out of his m—, his head. We had a great time doing it. I mean, obviously, unlike Slumdog, on this, we used two or three, three or four pop songs as well, for deliberate reasons. And so there’s not quite as much of his score as there was on Slumdog, but he could have scored it all. He was quite happy to. I said, no, we have to keep, I wanted the feel of an already existing song for all sorts of reasons at different times.

PRIDE: The film’s insanely upbeat. I didn’t feel claustrophobic or anxious. But then we already know, as in a Greek tragedy, we know what’s going to happen—

BOYLE: Yeah, yeah.

PRIDE: This is an interesting thing, like Titanic; you can be as giddy as you want to be because you know the result. Pretty much, audiences are going to know what Aron has to do. The actual moment of contact, the sound design as he approaches the nerve, that’s the only time I was flinching. Even though he’s fading and ebbing and hallucinating it’s just… I’d even say it’s a light film.

BOYLE: [leans in, quieter] But it’s… I always wanted to do it in that way, I always thought, when I read it, when I read his book, which obviously is the starting point, apart from hearing the story, I found the chapters in the canyon exhilarating. I didn’t like the other chapters at all, where he was talking about his upbringing and his background story and stuff like that.

PRIDE: I only looked at the photo section this morning: not only is his kit the same—

BOYLE: Exactly!

PRIDE: But you have—

BOYLE: Oh, no, everything is the same!

PRIDE: The splatter on the canyon wall, you’ve got the same size, shape—

BOYLE: Yeah! But that picture is the one he takes at the end of the film, where he takes a picture of the hand that he’s left behind. The rock is exactly the same, the rock that—

PRIDE: And the S-tree above him—

BOYLE: It’s weird, isn’t it? I mean, it’s weird having that document, to base everything on.

PRIDE: It’s freeing, isn’t it? “I’m going to be utterly real with this, then and only then, I’m going to build out.”

BOYLE: Yes. That’s what we said to him. It’ll be… Because he was nervous, obviously. When I first met him, he was not even nervous; he was just completely blocked. He didn’t want to know about this approach. He wanted to do it as documentary where he kept control. But when I met him again in 2009, he was nervous about giving us the freedom to do it and I said, well listen, the only way to have a decent film is if you let us tell the truth through a certain amount of fiction. And I said if you tell it all through fact, it won’t work. And I said, I said, most especially, you won’t arrive at a point where you can tolerate him cutting his arm off. People will walk out. But I said, if you put people in a position where they’re on that journey with him… And they feel like they’ve been with him the whole time, and not with you, Aron, they’ve been with James Franco. ‘Cos that’s the other thing I said to him, I said, y’know when you cast an actor… you want to do a dramatized documentary, because you want to cast someone who looks like you… but you never see, because you keep him at a distance. I said, you’ve got to commit to someone and they become you. But I want us to watch James Franco go through what you went through and he’s called Aron Ralston, and he is Aron Ralston, and it is your story, but isn’t told through a slightly different medium, which is me, James and the cameramen and y’know and on we go. To give him his credit, he did, he agreed, not reluctantly, but with reservations, but he appreciated it by the end, I think. And it’s the way to get at the story best.

PRIDE: Franco this year, I mean, the feat of his performance in Howl…

BOYLE: I still haven’t seen it, I haven’t seen Howl.

PRIDE: He’s just got it all down.

BOYLE: Did he get it?

PRIDE: Yeah. It’s not mimicry, he inhabits it, it begins with mimicry—

BOYLE: He’s a very clever guy. He gives the impression of being stoned the whole time, and like half asleep? He’s as sharp as anything. And he picks up things so fast. I was amazed at that. And it is a front, that stoned thing, to keep everybody at bay. That’s what he’s doing, he’s sussing you out even though you think, “Does he know I’m here?” He’s kind of sussing you out. Yeah, I liked him a lot.

PRIDE: He’s the animal just waiting to pounce.

BOYLE: Yes, he is, isn’t he?

PRIDE: This is the Sisyphus myth as a Western.

BOYLE: Yeah. A man and a rock.

PRIDE: One man against the landscape except Utah’s John Ford-style horizon is above him.

BOYLE: Yeah, slightly outside, obviously. The weird thing about it is, ‘cos people… what we tried to do, deliberately, we tried to not to do the… What I didn’t want to do is what you’d normally do, which is every three minutes you cut away to a landscape shot and show, y’know—

PRIDE: Like in movies with relentless establishing shots that break any sort of psychological tension?

BOYLE: I agree, I agree. And even more so, I thought, because he can’t see any of this. All he can see is the sky, he’s got the blue sky— he could be on top of a building, in a box on top of a building, because he just can’t see anything. I thought, why should we be doing all that the whole time? You’ve got to try and as much as possible make it an immersive, first person experience that you go through.

PRIDE: The vitality of his mind is what you’re getting at, the visual vocabulary getting more vivid as he begins to hallucinate. The intensity of the hallucinations increases as he grows weaker—

BOYLE: Yeah.

PRIDE: And the rainstorm saves him then! That’s bizarre. “I’m gonna drown! No, I ‘m saved!”

BOYLE: [big laugh] I love that. He was obsessed with rain, with the potential of flash flood. Which was extraordinary of course, because we thought—

PRIDE: You don’t flag that. It just occurs.

BOYLE: Yes, it just happens.

PRIDE: Raindrops then, “Yiiiiiikes!”

BOYLE: Yiii! No, he was obsessed with the possibility of flash floods happening, which is ironic considering. It just shows you, doesn’t it, we’ll hang onto life as long as we can. So he’s dying… but he’s obsessed with the danger of dying in a different way, which is flash flood drowning him.

[Both laugh.]

BOYLE: Yes, bizarre.

PRIDE: The second time we see the Scooby Doo, in his imagining of where the girls have gone that night, is he waving with the right arm, the same arm that’s pinned?

BOYLE: [laughs] What, Scooby Doo?

PRIDE: The balloon moving down the road at night, I think he’s waving with—

BOYLE: That same hand? I think he is, actually. I think that is his right hand. But I think that was dictated by the Scooby Doo franchise, to be absolutely honest.

PRIDE: Why two DPs?

BOYLE: Well. This is very interesting. Because when we were setting it up, I was thinking about the limitations of the story in terms of how reductive it is, and obviously, particularly this approach, that basically excludes everyone apart from at the beginning and the end, and just one person. And obviously Franco is a fantastic actor who can display many moods and tones, and indeed he starts to go multi-character, voices, eventually in the chatshow [part]. And I thought, I can provide a bit of contrast through and variation through music and rhythm and editing and stuff like that. I can keep it changing as well. And I thought, maybe, we should get two cinematographers and from different disciplines. And their work will be, there’ll be a stylistic variation within certain sequences. That didn’t work at all! Because although we got these, we got Anthony [Dod Mantle], who’s from northern Europe, and Enrique [Chediak], who’s from Ecuador, with a different sensibility you’d think… and they both shot the same way!

PRIDE: Wow.

BOYLE: That’s because, I realized, in retrospect, what dictated is not a style that they bring to it, it’s actually what James does, the way James performs. They follow. However, the other advantage, and this did work, was that I could keep shooting seven days a week rather than have a break.

PRIDE: Like an old-school Hong Kong director.

BOYLE: Yeah. I didn’t want a break. I thought, for this kind of story, it’s wrong. To reflect? I thought, if I’d’a got it right or not, reflection is not gonna fuckin’ help it, I’ve gotta kinda… Once I put my nose on it, I’ve gotta keep going until it’s done. Like him. Once you go in the canyon, you’ve just gotta do it. You can’t legally do that with your employees. So I had two crews, I had a blue crew and a red crew, and I would stagger their days off. Sometimes they’d shoot simultaneously, sometimes they’d shoot separately on different sets, different elements like stunts, involving stunt doubles or falling, that kind of stuff. There was lots of material for them to shoot but I meant I could continue. James agreed to do six days a week and he would have done seven days a week but they seventh day he had to go to New York to show his face at these classes that he has to go to. So we would finish, whatever time on a Sunday, he would finish on a Sunday night, and he’d leave on the overnight plane to New York. Then he’d show his face on Monday morning class and then he’d get the flight back to L.A., sleep in the airport so that he could get the first flight to Salt Lake City on the Tuesday morning and be on set for 8am.

PRIDE: It’s like a work-release program where you’re lying to your parole officer.

BOYLE: It’s just… It’s like.. [grins as he trails off] All that obsessiveness, that compulsiveness is reflected in the film. If you’d made it in a leisurely way, it would have looked leisurely, y’know? Hence, the ambition of the DoPs didn’t work out in one sense, but it did in another way, multiple times.

PRIDE: You saw the opportunity and ran with it within the parameters you were allowed.

BOYLE: Yes! Absolutely.

PRIDE: Most of the look continues with the the saturated, grainy, post-DV palette you’ve grown fond of. There are things like the wide shot of the blue night sky with the car full of half-naked party people, this looks like an Icelandic hallucination…

BOYLE: That was Park City! We did that up at Park City. When we started shooting, it was quite wintry in Salt Lake, and unfortunately, we thought it’d be dry in the desert, but actually, because the desert’s high, it was also wintry. The memory of the people…

PRIDE: It’s just a layered, vital image, snow is flying, light sources are unnatural, the music’s going da-da-dah—

BOYLE: It’s triggered by, it’s a music-trigger memory. The music pops into his head and this image that he associates with it, it’s “Ca Plane Pour Moi.” Plastic Bertrand. Yeah!

PRIDE: I remember dancing to that song.

BOYLE: [laughs] That’s what you hope, that’s what I hoped, people would go, [high-pitched sound of illumination] “Oh! Oh!” You kinda remember it like that. Because songs, sometimes you remember them, and you think, bloody hell! What was that song I used… ! And they get forgotten. There’s a great ABBA song that they’ve never really sung, called “The Day Before You Came.” Oh! What a song! It’s an amazing song. And it was [covered by Blancmange] and I don’t think they ever did anything else. [It was the last song ABBA recorded.] And I was thinking of it the other day, it was like, “Oh!” “Don’t I know this song? Is this part of my collective memory? I think it is!”

PRIDE: [flipping through photo insert] That caption, that cutline Aron puts in the book, “The Last Photograph Of My Right Hand.”

BOYLE: Yes. They went back and rescued the hand. In fact, while we were prepping, we asked to see the photographs. ‘Cos we asked Aron, and he said, I haven’t got them, the rescue services have them. And I’ve never seen them. So we asked to see them, and they sent them to us. [whispers] It was shocking, Oh!, i-yi-yi. I think it took about twelve blokes when they went back to shift the rock when they went back in and they pulled the hand out and held it up and photographed it. Ohhhhh. That will make your stomach turn. It was like, Fuck. It was… flattened. You know, like in Roger Rabbit? At the end, when he gets flattened, when the villain gets flattened? It was like that, it was flattened in a way… if you’d seen it, it would be, “I don’t believe that.” If you had no context, you’d think, “What’s that?” But in context, it was like, ohhhhhhhhrrrr. Rough.

PRIDE: Do you feel this is a claustrophobic movie?

BOYLE: No, I never thought of it as claustrophobic. In fact, I don’t think he talks about it being claustrophobic in the book at all. He doesn’t mention it like that. I think his biggest, his issue in the book is that at night it’s fucking cold. That’s his problem, trying to keep warm, ‘cos he’s only got, he piles all his stuff on to try to keep this bloody cold wind out of him. Yeah. That’s what they are, that’s how they’re formed, those slot canyons. Some of it’s flash floods, but a lot of it is wind and microscopic particles of dust in the wind over generations, well, not generations,millennia. Just wearing it out. It’s so smooth, some of it, it’s been sanded down, literally, to fine sandpaper.

PRIDE: Why titles with numbers in them?

BOYLE: Somebody told me the other day you should always do that, it’s a bit like having a wedding in your title. A wedding. They always work! People are trying to work out the numbers, even if they don’t like the film very much, they’ll spend time thinking. What’s this about? What does this relate to? Yeh.

PRIDE: The film is subjective; you’re portraying a vision. A movie ought to be a hallucination as compelling as a religious vision, and Aron’s fluctuating grasp on reality and memory is what you’re bringing to life.

BOYLE: Yes. I couldn’t get it out of my head. I tried, in the 80s, when I wasn’t a filmmaker, but I would have liked to have been! I tried to, there was an amazing story about an Irish journalist, called Brian Keenan. He was kidnapped in Beirut for five years and held hostage, chained to a radiator. And for three of those years, another guy was chained to the radiator as well. A British guy, a British journalist called John McCarthy. And Keenan is a difficult Irishman, as he admits in this amazing book he wrote about it, called “An Evil Cradling.” And he’s a difficult Irishman, he does not like Englishmen. And their bond they grew together? Was extraordinary. But chained to a radiator for five years! I thought what an amazing film that would make.

PRIDE: You were compressing the story for years, you just didn’t know it. You’ve made that film now.

BOYLE: In a bit more accessible way. There’s another one actually that I got involved with and didn’t work out called “The Birthday Party,” which is not the Harold Pinter play. It’s a novel; it’s not a novel, but a real-life experience of a guy who was kidnapped in Manhattan for a weekend and held in a bedroom in Brooklyn by these young black guys. [deep breath] And he had a bag on his head for all the weekend. And they fed him. And had sex on the bed beside him. And all the time he sat there with his bag on his head. And they threatened to shoot him. It’s an extraordinary, I thought, [whispers] that would be an amazing film, if you could shoot the whole film inside that bag. And you can just see out the corner, underneath, and could just see them have sex, then they bring a gun, threaten to shoot him unless he gives them the PIN number on his card for the ATM machine. Anyway, I’ve always been interested in that stuff.

127 Hours expands Friday to 23 markets and an additional 25 on Friday, November 24.

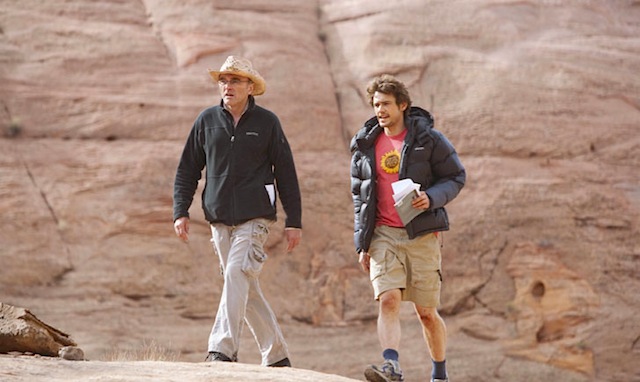

[Photos: Chuck Zlotnick; Danny Boyle by Ray Pride, from Sunshine publicity tour, 2007.]