By Kim Voynar Voynar@moviecitynews.com

Sundance Review: Project Nim

With Man on Wire, director James Marsh took a story that necessitated being pieced together with reflective interviews and archival footage of past events and wove it all together into a cohesive whole that resonated powerfully as it told the history of Phillipe Petit, a daredevil who pulled off a number of dangerous and unbelievable stunts, most notably stringing a wire between the twin towers of the World Trade Center, then under construction, and walking across it.

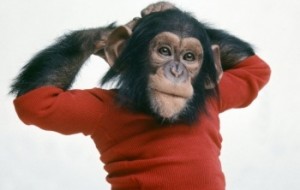

With his latest film Project Nim, picked up by HBO Documentaries right before Sundance kicked off, Marsh tackles an equally challenging documentary subject: the story of a chimp named Nim, taken away from his mother at birth and raised by humans as the subject of a scientific experiment to see if humans and chimps could learn to communicate through sign language.

If it sounds like subject matter more appropriate for, say, a dry dissertation on animal rights, it is; after all, how on earth does a filmmaker make a compelling biographical film about an animal? But once again, Marsh uses his remarkable storytelling ability to take factual material and construct of it a tale that has all the elements of a narrative tale: a compelling story arc, a tragic victim in Nim, the chimp at the center of the tale who’s raised in a sterile environment completely separated from other members of his own species, and a veritable revolving door of human characters who play the roles of heroes and victims — sometimes wearing both hats at different points in the story.

Nim had the misfortune to be chosen as the subject of an experiment that was the brainchild of Columbia University behavioral psychologist Herbert Terrace. Back in 1973, when Project Nim began, the idea of researching animal language and human-animal communication was a groundbreaking concept to explore (apparently it still is, as according to the press notes Terrace is still parceling an academic career out of primate research).

But this is Nim’s tale, with Terrace relegated to the role of a mustache-twirling Snidely Whiplash, and in the current day interviews Terrace plays that role to a tee, while posturing as though he thinks he’s Dudley Do-Right — or at least as if the whole sordid story is little more than an academic “oops.”

The film begins with newborn Nim being snatched from his captive mother, Carolyn (who, we learn, had previously had six other babies taken away from her in the same way) with tranquilizer dart and no ceremony from his mother. Nim’s a chimp, not a human, but the language the humans use in justifying the callousness with which they take the baby away from the mother with no regard for the impact that might have on either makes one wonder if any of these scientists have ever heard of the research of Jane Goodall.

Nim is placed into the lively, busy New York City brownstone home of former psychology student Stephanie Lafarge and her husband Wer, a successful “hippie poet,” and their combined brood of seven kids, where he quickly latches onto Stephanie as a maternal figure. Stephanie’s instructions were to treat Nim exactly as she would a human child, and that’s exactly what she did, even going so far as to try breastfeeding him.

While Baby Nim quickly acclimated to life in the busy Lafarge household, Stephanie’s laissez-faire parenting approach became a problem for the study when it translated to Stephanie having no documentable routine, education plan or daily journaling of Nim’s behaviors. Enter Laura, a pretty, bright 18-year-old psych undergrad who initially came on board to help teach Nim but ended up essentially taking the project over, and then falling under the sway of Terrace, who, in spite of his bad combover, was apparently quite the ladies’ man with his female students.

Eventually, Terrace removed Nim from the Lafarge family and set up the project up in a big country estate, with Nim and his teachers living together and making forays to the Columbia campus to work in a dreary cinder block cell of a classroom. And Nim did indeed learn sign language, but he also remained very much a wild beast, capable of biting and getting physical with his human tribe in much the same way as he would have with other chimps in establishing social hierarchy.

Eventually, funding for the project dries up, and the rest of the film deals with what becomes of Nim after he’s no longer of use for Terrace’s project and the chimp raised as a human is tossed into a cage and used for medical experiments.

Much like Man on Wire, Project Nim is cut together from a mix of archival footage and stills, re-enactments of past events shot with actors, and interviews with the human subjects (the talented cinematographer Michael Simmonds, who shoots all of Ramin Bahrani’s films among other projects, is on hand to lend his particular visual artistry to the proceedings).

What Project Nim shows us is that while Nim and chimps generally may have characteristics similar to humans, and can be taught some signs to express what they want, that doesn’t make them human. How much right do we as a species have to subvert another species to our will, to use other creatures for our own purposes, however noble we might think our intent?

It’s hard to glean to what extent Nim is communicating in the human sense versus simply learning variations of the chimpanzee body language he would have learned had he been raised with other chimpanzees, but there’s a scene where Nim is introduced to another chimp for the first time in his life, discreetly captured by a film crew, in which he communicates with body language perhaps more clearly than in any moment when he used the sign language taught him by his human captors.

What is clear is that the humans involved with Nim, even those who had the best of intentions, did not all treat him humanely. Do good intentions outweigh grievous wrongs perpetrated in the name of scientific research? Well, we all know what the road to hell is paved with …