By Other Voices voices@moviecitynews.com

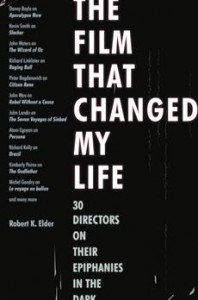

“The Film That Changed My Life”: Richard Kelly On Brazil

Robert K. Elder’s latest book, “The Film that Changed My Life,” came together as he met filmmakers as part of his regular writing assignments, and then got them to expand on one film that changed their lives, and what form that “change” took. Among the thirty equally appealing conversations, Kevin Smith talks Slacker; Danny Boyle, Apocalypse Now; Atom Egoyan, Persona; John Woo, Mean Streets; Frank Oz, Touch of Evil; Rian Johnson, Annie Hall; and Steve James, Harlan County U.S.A. In his introduction, Elder cites Reservoir Dogs as his own touchstone. At 17, it was “the first time I felt the presence of the director: a full-on personality and force of style imposed on the movie. Tarantino’s DNA was on each frame of celluloid.” Donnie Darko director Richard Kelly chose Brazil. Here’s an extended excerpt of their intense appreciation of Terry Gilliam’s masterpiece. [You can buy the book here. The official “The Film That Changed My Life” website is here.]

Robert K. Elder’s latest book, “The Film that Changed My Life,” came together as he met filmmakers as part of his regular writing assignments, and then got them to expand on one film that changed their lives, and what form that “change” took. Among the thirty equally appealing conversations, Kevin Smith talks Slacker; Danny Boyle, Apocalypse Now; Atom Egoyan, Persona; John Woo, Mean Streets; Frank Oz, Touch of Evil; Rian Johnson, Annie Hall; and Steve James, Harlan County U.S.A. In his introduction, Elder cites Reservoir Dogs as his own touchstone. At 17, it was “the first time I felt the presence of the director: a full-on personality and force of style imposed on the movie. Tarantino’s DNA was on each frame of celluloid.” Donnie Darko director Richard Kelly chose Brazil. Here’s an extended excerpt of their intense appreciation of Terry Gilliam’s masterpiece. [You can buy the book here. The official “The Film That Changed My Life” website is here.]

Robert K. Elder: Terry Gilliam called this film “Walter Mitty meets Franz Kafka.”

Kelly: I would best describe Brazil as a portrait of bureaucracy run amok, or capitalism run amok. It’s probably the most visionary example of an alternate universe portrayed with such incredible logic. It’s incredibly absurd, but it’s incredibly accurate to the system that exists in our world. I would call it one of the most profound social satires that has ever been filmed. It is unlike any film that has ever been made before or after. It is also incredibly difficult to describe to someone who has never seen it. You just have to say to someone, “This is a film you must see, and you must experience it without any preconceived notions of what you’re going to be watching.” I wouldn’t even know how to explain it to someone or sell it to someone. That’s what’s so great about it.

How did you first hear about the film?

Kelly: I grew up as a huge fan of Time Bandits. Time Bandits had always affected me as a kid, and I had memories of that from when I was very small, and it frightened me. I remembered when the dwarves came into the little kid’s bedroom and started pushing his bedroom wall and it opened up to this abyssal tunnel, and the image of them falling from this light grid in the sky captured my imagination as a really young child. Those images stayed with me—they burned themselves into the back of my head. I started reading about Terry’s other films, having seen The Fisher King prior to that. I was aware of The Adventures of Baron Munchausen but I had never seen Brazil. I grew up in Midlothian, Virginia, where you’d be lucky to find Brazil in a Blockbuster Video. It wasn’t a film that was jumping off the shelves and available to someone in a town like Midlothian, Virginia. When I arrived in film school, I suddenly found myself with this gigantic library of LaserDiscs, and Brazil was one of the first ones I checked out at the library.

Most people, when they say “the film that changed my life,” they mean the film that made them want to be a director, propelled them to film school. But you saw the film when you were already in film school. How did it change your life?

Kelly: In my freshman year of college, I was in the school of fine arts and hadn’t yet been accepted into the film program. I had gotten an art scholarship for a lot of illustrations and drawings and paintings that I had done in junior high and high school. I immediately started dropping art classes and started taking the general film courses my freshman year and got guest access passes to the film library, so I knew I was trying to get into the film school, but I wasn’t there yet. I was more in that transitional period, where I was trying to gain confidence and put together my vision and my voice as an artist and a filmmaker. Having discovered Terry’s work and seeing that he followed a similar course, beginning in the visual arts as a cartoonist working with Monty Python, I felt a kinship to him. The visual design in Brazil is so astonishing, my head almost exploded. You have to give Terry, Tom Stoppard, and Charles McKeown credit for explaining what was wrong with the world in very elegant strokes that are alien to us because the world is not our own, but it is incredibly familiar because it is absolutely our own.

Gilliam has said Brazil was a documentary. He said he made none of it up.

Kelly: It is a documentary film with the brushstrokes of a profoundly mad genius who can create a fantasy world, but he created a fantasy world literally within—he re-created our world in a different visual language. I had never seen that done in any other film. Fritz Lang’s Metropolis is maybe the closest  approximation, but I think that Brazil certainly said many things that Metropolis couldn’t, maybe because Lang didn’t have the benefit of sound. Gilliam has an artist’s eye. He is someone who sees every frame as an oil painting. He meticulously assembles every frame with so much detail as to make that image worth watching dozens and dozens of times. You end up with a film that is timeless. It becomes this essential viewing experience that seems to ultimately get better with age because as one matures, the meaning of the film matures. That meticulous attention to detail is something that only the greatest directors are capable of. [There are] sight gags you literally need to watch three or four times to catch all the jokes hidden in every frame. They’re not just crass, empty, cheap laughs; there’s profound irony invested in every frame, just an extraordinary amount of social criticism invested in each one of the gags.

approximation, but I think that Brazil certainly said many things that Metropolis couldn’t, maybe because Lang didn’t have the benefit of sound. Gilliam has an artist’s eye. He is someone who sees every frame as an oil painting. He meticulously assembles every frame with so much detail as to make that image worth watching dozens and dozens of times. You end up with a film that is timeless. It becomes this essential viewing experience that seems to ultimately get better with age because as one matures, the meaning of the film matures. That meticulous attention to detail is something that only the greatest directors are capable of. [There are] sight gags you literally need to watch three or four times to catch all the jokes hidden in every frame. They’re not just crass, empty, cheap laughs; there’s profound irony invested in every frame, just an extraordinary amount of social criticism invested in each one of the gags.

I think the moment that got me was when Lowry was running through the shopping promenade, and Robert De Niro’s character is suddenly overcome with hundreds and hundreds of sheets of paper blowing in the wind, and they start affixing themselves to his body. He’s just standing, and there’s nothing but paper blowing in the wind in every direction. That’s when the film got me, and I finally understood what it was about. The whole film was about that scene. On one level, it was about how the system—bureaucracy or capitalism or whatever you want to call it, whether you want to get into a Marxist critique on modern life—how our means and methods of production and the Ministry of Information retrieval, how all these institutions can ultimately suffocate our humanity. And that’s exactly what happened to Robert De Niro’s character in that scene. He ceased to exist, and there was nothing left but a bunch of paper. It was just a profound image and, to me, one of the more emotional images in the film. With the terrorist bombings and the plastic surgery gone bad, we are living in Brazil right now. We get closer to Brazil with each passing week.

Gilliam first toyed with calling the film The Ministry or, more popularly, 1984½, which was a tip both to George Orwell and to Federico Fellini for 8½. One critic called it “1984 with laughs,” but Gilliam’s totalitarian society is one that is absent of Big Brother. The system itself is the antagonist; there’s no physical villain. How does that change the viewing experience?

Gilliam first toyed with calling the film The Ministry or, more popularly, 1984½, which was a tip both to George Orwell and to Federico Fellini for 8½. One critic called it “1984 with laughs,” but Gilliam’s totalitarian society is one that is absent of Big Brother. The system itself is the antagonist; there’s no physical villain. How does that change the viewing experience?

Kelly: It makes it more demanding for the viewer. There are plenty of villains in history, but what you don’t realize is that behind that villain lays an infrastructure, and it is the infrastructure that empowers that villain. And I think Terry and his collaborators were being very ahead of their time and looking less at a figurehead and more at an infrastructure that can be manipulated to create a figurehead, like… I don’t want to mention any names here. Thank God Terry has such a great sense of humor because that’s where his voices come from, ultimately. Aside from his humanity or his sense of moral anarchy or his visionary visual imagination, it is his sense of humor that ultimately keeps him alive.

Brazil is also famous for Gilliam’s fight with [executive] Sidney Sheinberg, when he delivered a movie seventeen minutes longer than was contracted, so he took the film away from him and it was a yearlong battle before they released it here. Were you aware of this when you saw it?

Brazil is also famous for Gilliam’s fight with [executive] Sidney Sheinberg, when he delivered a movie seventeen minutes longer than was contracted, so he took the film away from him and it was a yearlong battle before they released it here. Were you aware of this when you saw it?

Kelly: No, I wasn’t and that’s why, in subsequent years, I have become so obsessed with the film, because having to observe those battles on my first film and seeing and reading the history—there’s a great book called “The Battle of Brazil” [by Jack Mathews]—and reading about the fight he put up gave me a lot of confidence. I never had to go to the lengths with Donnie Darko that he had to, but I had to fight like hell and I didn’t win every battle. They gave me a director’s cut later, so that was an indication that if you know you’ve done a good job, and you know that you have a voice and you’re confident, it may get you in trouble in the short term, but in the long term all that matters is the film that is released. It isn’t the fight, the memos, or the words that are exchanged—it’s your art, it’s what you are going to be judged for when you are dead and buried, and it’s worth fighting for. Thank God that Terry fought for Brazil. Had “love conquered all,” we would have been denied a real masterpiece.

The Los Angeles Film Critics Association forced Universal’s hand; they named Brazil Best Picture of the year and Gilliam Best Director. It’s the one documented case in which critics banded together to save a film, and that’s a pretty complex relationship. What is the role of the critic? Is it to critique art or to influence it?

Kelly: Their perfunctory role is to critique art, but in every critic’s heart is a desire to better the art form, in their dialogue, in their criticism, in the critical literature they are creating. They want to promote good films and suppress the bad films, and hopefully make the process better—contribute and support bold, risky, innovative filmmaking. It should be the duty of any film critic. I think that if you ask any film critic if he or she has an agenda to support those films, that critic will say “absolutely.” It really can make all the difference. You see it all the time, like with Patty Jenkins’s film Monster, when Roger Ebert was one of the first critics out there to herald not only Charlize Theron’s performance but also the film itself. An important film critic like Roger Ebert can certainly rescue a film from oblivion, and I think that has to warm any critic’s heart to have the power to do something like that.

Gilliam told the New York Times in 1986 that “you can’t talk about artistic values or social values or philosophical values; economic values are the only ones that count.” Has Hollywood changed?

Kelly: I think economic values have only been foregrounded in the vertical integration of studios. We’re now seeing gigantic corporations merging with one another. There’s talk of synergy and vertical integration. Karl Marx is chuckling in his grave somewhere because it all comes down to one word: money. It costs a lot of money to create these works of art, and ultimately they are not seen as works of art any more by the people who are writing the checks. The fight has become that much more difficult, and you have to be that much more savvy and manipulative in order to work your way into the system and somehow emerge as a piece of art, not a piece of commerce.

Can you point to any specific ways that Brazil influenced your work?

Can you point to any specific ways that Brazil influenced your work?

Kelly: If I’m taking inspiration, or if I’m going to blatantly rip off my favorite artists, I try not to make it quite so blatant. But I think the greatest thing I learned from Terry is that every frame is worthy of attention to detail. Every frame is worthy of being frozen in time and then thrown on a wall like an oil painting, and if you work hard on every frame, the meaning of your film becomes deeper, more enhanced. New meaning emerges in your story because of your attention to detail. It is also developing a visual style that is your own, that is hopefully unlike anything that has been done before. He gave me something to aspire to as a visual artist but also as a storyteller, as one who aspires to be a social satirist. I have a long way to go, but I aspire to do some of the things that Terry has done, and to do them as well as Terry has done. It’s about being thorough, and having a great sense of humor and being able to laugh at the end. I look at the film now, and it’s more timely than ever. It makes more sense now than it did in 1985. That’s a testament to how much of a documentary it really is.

There are two kinds of satire. There’s Juvenalian satire and there’s Horatian satire. One of them says the world is a shitty place but in the end we’ll all be taken care of, and the other says the world is a shitty place and in the end we’re all fucked. One sees the glass as half-empty and the other sees the glass as half-full. Some may accuse Terry of seeing the glass as half-empty, but I think, really, in his heart, he sees it as half-full.

[© Robert K. Elder. Reprinted by permission. You can buy the book here. The official “The Film That Changed My Life” website is here.]

I’ve never been Gilliam’s biggest fan, but Kelly is my favorite director, and I can certainly appreciate the impact Gilliam’s film obviously had on him.