By Ray Pride Pride@moviecitynews.com

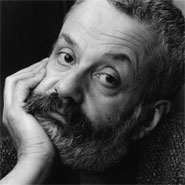

Mike Leigh on TOPSY-TURVY (from 2000)

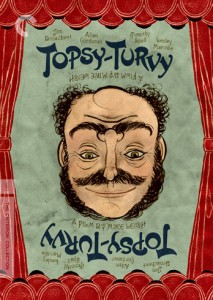

Topsy-Turvy is out now on Criterion DVD and Blu-Ray. Here’s an interview I had with writer-director Mike Leigh at the time of its theatrical release, first published in January 2000.

Topsy-Turvy is out now on Criterion DVD and Blu-Ray. Here’s an interview I had with writer-director Mike Leigh at the time of its theatrical release, first published in January 2000.

MIKE LEIGH AS ARTIST MAY NOT BE ENTIRELY RAW NERVE, but he often is as interviewee.

Topsy-Turvy is worthy of many polished adjectives—magnificent, hilarious, heartbreaking and certainly improbable. How could one of the best films released in early 2000 be a story of the making of Gilbert and Sullivan’s “The Mikado” at the end of the 1800s? Because of Mike Leigh—that’s how.

Leigh’s speech is filled with pauses and backtracks and refinements. The subject of his working methods—months of improvisations refining a script that only Leigh holds in his head—is one that he doesn’t care to go beyond practiced boilerplate. And while the secrets of “what we do as actors and directors” is the meat of Topsy-Turvy, one question of mine, based on a wonderfully dense anecdote told to me by Jim Broadbent, leads to a brusque (if smiling) reply of “I don’t know about that. Sorry. Can’t help.”

Leigh’s work, even before the recent Naked and Secrets and Lies, has been uncommonly intimate with the details of his characters’ lives. Yet he’s one of the most astute practitioners of unbroken takes. There’s a marvelous one when the battling composer Arthur Sullivan (Allan Corduner) and librettist W.S. Gilbert (Jim Broadbent) finally face each other to work out their differences. They can’t look each other in the eye, but they review their differences while sucking on candies. Leigh says that because of the period setting, “We struggled because we did more than we normally do. It wasn’t just a kind of distillation  of improvisation. We [worked with what we learned from the extant] correspondence as well. The thing with the sugar kind of crept in just as a joke, really. I said, ‘Well, actually it’s great, why don’t you just do it?’ They were sort of slightly sending it up. I said, ‘Play the scene with that’ and it liberated it completely. Because what’s fascinating about the whole thing, which I’m just doing sort of a quasi-bio-pic, it’s not really a bio-pic at all, where you make famous people behave like for real. So we retrospectively invented the Swiss sugar, which is completely not a piece of research.”

of improvisation. We [worked with what we learned from the extant] correspondence as well. The thing with the sugar kind of crept in just as a joke, really. I said, ‘Well, actually it’s great, why don’t you just do it?’ They were sort of slightly sending it up. I said, ‘Play the scene with that’ and it liberated it completely. Because what’s fascinating about the whole thing, which I’m just doing sort of a quasi-bio-pic, it’s not really a bio-pic at all, where you make famous people behave like for real. So we retrospectively invented the Swiss sugar, which is completely not a piece of research.”

Which passes for an answer when talking to Leigh. Another scene that seems ripely actorish at first, belongs to Timothy Spall. A Leigh regular, Spall plays Richard Temple, who is the Mikado. He and the other actors speak in a hilarious, cracked continental polyglot. Yet an unlikely reflection of his, filled with ego, love and hurt finds him ruing a cut scene, and his life, with the Beckett-worthy “Laughter. Tears. Curtain.”

Leigh nods. “And of course he and I share this particular predilection for Dickens. He has this great [presence] and he knows quite a lot about [the era]. The great and fortunate thing about Richard Temple is there’s not very much known about him. Where there was a lot known, such as about Gilbert and Sullivan, we tried to use that and activate these guys as we researched them. But that left Spall and me free to create this Victorian “Ac-Tor,” y’know, which seemed very appropriate. When Gilbert cut [Temple’s big] song , which he did [in real life], and when the chorus went to [Gilbert] in a posse, in reality, we had no idea whether Temple cared or was relieved in reality. But certainly it was very useful to make him this guy [who cared].”

The idea of demonstrating what actors and directors seems like must have been an overriding concern as Leigh assembled the story. “Yes. It was a given, yeah. I sort of felt, in the way that I suppose everybody does, a lot of artists do, at a certain  stage, you do a kind of self-portraiture. But it isn’t in any literal sense, that. But I just felt it would be good to look at what we do, really. And y’know, as you know, I always shy away from or I more naturally gravitate towards ordinary lives, lives like lots of other people, really, the unextraordinary. I just thought, y’know, these guys are, let’s, as I say, subvert that. Let’s look at, these are real people, then. But yeah, the assumption was let’s do a theater… film.”

stage, you do a kind of self-portraiture. But it isn’t in any literal sense, that. But I just felt it would be good to look at what we do, really. And y’know, as you know, I always shy away from or I more naturally gravitate towards ordinary lives, lives like lots of other people, really, the unextraordinary. I just thought, y’know, these guys are, let’s, as I say, subvert that. Let’s look at, these are real people, then. But yeah, the assumption was let’s do a theater… film.”

Topsy-Turvy is filled with precise observations of the lives of its many characters, yet despite its length, is an incredibly taut film. “I think that’s right. It won’t surprise you I’ve had to put up with a lot of nonsense about length. The fact is, it is one minute short of two hours forty and I don’t think there’s a spare moment in it, really. I think it’s absolutely all there. Nobody is more critical of long, boring films that don’t say anything than I am.”

While many dwell on performance in discussing his work, Leigh uses many simple cinematic strokes to tell his stories. “I mean, the fact is I get pretty depressed when people go on and on about it as if it were just a film about acting. I mean, these films are very cinematic. I have worked for a very long time with Dick Pope, who is a great cinematographer, and we push each other to the limits. We do very sophisticated cinematic things. We don’t just point the camera at the actors in a kind of naive way. Cinematographically and photographically, it’s a major achievement, this Topsy-Turvy, it really is, y’know.” [My indieWIRE review from the film’s New York Film Festival debut is here. You can sample our conversation about Naked here.]