By Noah Forrest Forrest@moviecitynews.com

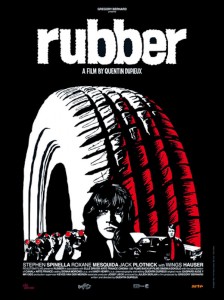

RUBBER – The Best Psychokinetic Tire Movie Ever!

If you only see one movie this year about a sentient tire that kills people with the power of his mind, make it Rubber.

I had heard a lot about the so-called “killer tire” movie that played at Cannes and then went on the festival circuit. The folks who had seen it seemed cagey about what exactly they had seen, only releasing tantalizing hints that it wasn’t what you might expect it to be. I didn’t really expect a movie about a killer tire to be anything really, so my interest was piqued in what seemed like a concept fit for a B-movie.

The interesting thing about Rubber is that it has just as much in common with Jean-Luc Godard as it does with Roger Corman. Right from the get-go, it is clear that this absurd tale is about more than it’s letting on, with the film opening with a long monologue told straight to the camera by a man in a police uniform (Stephen Spinella). He tells us that a lot of the choices made in some of our favorite films are made by their directors for basically no reason, that this element of “no reason” is an important one in some of the best movies ever made. He cites specific examples from movies like E.T. and The Pianist then goes on to talk about more than just movies, asking why we can’t “see the air all around us.” It’s all very philosophical and despite the fact that he tells us that things happen for no reason, it’s clear that this movie does have a reason and a purpose and is not just a bunch of nonsense.

The director, Quentin Dupieux, is someone to watch. If he wanted to make something more conventional, he’d be great at it because he clearly knows the rules of cinema, which makes it easy for him to break those rules repeatedly and constantly. He takes a lot of bold risks with this film, the biggest being that this isn’t really a movie about a killer tire at all, but a movie about watching a movie about a killer tire. Dupieux employs a Greek chorus of folks who are in the desert with binoculars watching the movie about the tire play out before them and they comment on it, which is already a pretty strange strategy, but then beyond that he has certain performers in the “movie” who know that it’s all fake and a certain member of the Greek chorus who doesn’t want to comment, he just wants to see the movie. If this all sounds confusing, I promise that it isn’t. Well, maybe a little bit.

While the point of all this might not be readily apparent, I think it does cut to the heart of what it means to watch a movie and how that intersects with what it means to be a person. And a big part of that is that sometimes we have to accept that things happen for “no reason” and that sometimes we have to jump into action rather than simply watch things unfold before us. I think it’s interesting that most of the film takes place outdoors, with very few scenes happening inside houses or motels; even the car that is drive by Roxane Mesquida (who the tire falls in love with) is a convertible. I think it’s a comment on the fact that we usually sit indoors when we’re watching a movie and here’s an audience of people watching a movie outside.

When I made a reference to Godard earlier, I wasn’t do so blithely. Dupieux’s tactics and techniques are what Godard strove to do, but so often failed at, which is communicating ideas with the cinema. And sometimes, Godard’s ideas were about anarchy and socialism and in a film like Week-end about the tenuous fabric of boring nothingness that holds modern society together. I think Godard failed in Week-end and in Pierrot Le Fou, films which comment on themselves as they unfold, because he didn’t particularly care about the audience’s entertainment in the way that, say, Truffaut would have. Godard is a very obvious filmmaker, one who would rather use a sledgehammer to get his point across than use anything resembling subtlety. (There endeth my Godard rant) Dupieux succeeds with Rubber because he makes what he purports to be the “point” of the film, which is that it’s not really about anything, but then crams in enough symbolism and philosophy to make us believe that it truly is about something. But what Dupieux really excels at is making us care about what happens despite the fact that the most developed character is the tire. What’s interesting is that we don’t care about what happens in the literal sense, but rather from a ideological perspective, in terms of what will be the final point that he’s trying to get across.

And then it ends with what I can only describe as both an homage and a middle finger to what modern-day cinema consists of.

Rubber is definitely not a film for everyone. In fact, I imagine most people will be turned off to it in the way that a lot of people are turned off by a film like Contempt (incidentally, my favorite Godard film), because it doesn’t do what we expect movies to do. My tastes are a little warped by years of watching unrelentingly bland, stale popcorn movies, so when I see a film like Rubber, that is aspiring to more than the usual, I get excited about it.

Rubber isn’t just the best movie about an animate tire who kills people with his mind that I’ve seen this year, it’s the best movie I’ve seen so far this year. It takes risks and goes to unexpected places. There is no way you will be able to guess what happens next. And when I put it that way, I’m making it seem almost conventional; and if there’s one thing this movie isn’t, it’s conventional.

“”He tells us that a lot of the choices made in some of our favorite films are made by their directors for basically no reason, that this element of “no reason” is an important one in some of the best movies ever made. He cites specific examples from movies like E.T. and The Pianist then goes on to talk about more than just movies, asking why we can’t “see the air all around us.””

Some unknown director’s character claims to have gotten into the minds of Spielberg(!) and Polanski(!) and came away claiming they made their shots randomly and not at all deliberatly. In other words, what he really claims is to have been able to deconstruct their creative process based on what he saw and reversed engineered it back to decide that the very sense of “no reason” he was feeling was made for no reason as opposed to being exactly the type of feeling those directors aimed for.

It would be funny if it wasn’t so pathetic.

Proman, I think if you take that opening speech at its word, then you’re missing the point. It’s laden with irony, obviously.

i am still kinda confused so the point of this movie was for a director to show other people that he thinks modern day cinema is junk?

So… I just watched this movie and after reading that kinda understand the movie a little more.. I feel like I wasted an hour give or taker of my life… But the whole movie itself, I mean I kept getting confused!! Why did the guy in the wheel chair die? Why were the guys trying to poison the audience? And why did that guy who got shot three times not die? Why did the ambulance not know they were “acting.” Movie effing leaves you with questions, man.

I agree with confused. There were a lot of confusing things in there, and while I could gather that it was a movie about watching a movie and that there was some kind of point it was making, it didn’t quite express it very well to those of us who don’t know a lot of the theory behind films and theatre.

Also, I really, really wanted to see a B-list horror-comedy/ horror parody about a killer tire. Like, REALLY. They should re-make this as exactly that!

Though, that said, I was amused by & appreciated how a movie with a tire villian could be so tense in some parts, and how much expression they gave to a tire. That was really pretty impressive.

It was stupid I would have been better off watching paint dry. I was confused the whole time and it should never be wach by anyone again