By Mike Wilmington Wilmington@moviecitynews.com

Wilmington DVD Picks of the Week: Black Swan, Raging Bull, The Complete Sherlock Holmes Collection, Farley Granger

PICK OF THE WEEK: NEW

Black Swan (Also Blu-ray and Digital) (Three and a Half Stars)

U.S.: Darren Aronofsky, 2010 (Fox)

Darren Aronofsky specializes in cinema tales of the brilliantly sick, sickly brilliant. He spins, with white-hot intensity, barmy movie stories of a crazed math genius going nuts on the stock market (in Pi), of a family of lower depths junkies and pill-poppers flipping out together (Hubert Selby Jr‘s Requiem for a Dream), and of a battered, beaten-down over-the-hill old wrestler putting himself through hell for one last fight in a world falling apart around him (The Wrestler).

In his latest movie, the justly hailed but occasionally (understandably) ridiculed dance melodrama Black Swan, this unbraked chronicler of mad lives charts the psychological disintegration of a young, ambitious New York ballerina named Nina Sayers (played by Oscar-winner Natalie Portman with ferocious dedication), who’s been given the dream lead role of the swan princess of Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake at Lincoln Center and promptly — what else in a Darren Aronofsky film? — goes over the edge into some kind of madness: self-mutilation, paranoid fantasies and sexual hysteria.

As we watch, Nina whirls and leaps and goes delusional — and the camera seems to whirl and leap and go delusional along with her, executing wild leaps and dizzying spins, diving and pouncing and peeking over her shoulder, Polanski-like, wherever she goes. The ballet company’s seductive bully of a master choreographer, Thomas Leroy (played with a sneer by French star Vincent Cassell), casts Nina as the lead in Tchaikovsky’s classic ballet, replacing his former prima ballerina, Beth McIntyre (Winona Ryder, creating a self-destructive witch) — he’s simultaneously anointing Nina, and hurling her into hell.

Leroy tells Nina she‘s ideal casting for half the part (the role of the pure white swan) but not the other half (the wicked black swan). And Aronofsky then bombards us with Nina’s fears and desires, in scenes of dreamily voluptuous terror. The ballet studio and stage become arenas of paranoia. So does her home, an art-cluttered Manhattan apartment she shares with her painter mother Erica (Barbara Hershey).

Stricken with panic, Nina tears and rips at her own flesh — and then the cuts are mysteriously healed. She‘s flung into predatory sexual escapades or fantasies, involving Leroy, and also her main rival, Lilly (Mila Kunis), whom Thomas provokingly says is the perfect Black Swan.

As the fantasies (?) rage, Nina becomes ill, is berated by Thomas, attacked by Beth, played for a fool (maybe) by her rival Lilly, bossed by her devoted yet domineering mother. Amidst this accelerating chaos, the beauty and classicism and first night of “Swan Lake” (modernized by Thomas) looms.

These nightmares in Black Swan, concocted by Aronofsky and his co-writers Mark Heyman, Andres Heinz (original story) and John McLaughlin, are genuinely scary. We all know dancers suffer, actors suffer, writers suffer, artists suffer. (Hell, everybody suffers a bit, except maybe, at times, the upper income tax bracket guys. But artists maybe suffer more, because it’s part of their metier.) Yet Portman’s Nina — who sleeps (and, in one memorable scene, masturbates) in a doll-strewn and teddy bear-packed bedroom — goes through such intense anguish that, though possibly self-inflicted, it seems punishment enough for orgies of badness and sin, and not just with Mila Kunis.

How much of this is really happening? We know some it is real, some of it a dream, some of it is fears made flesh. But we can never be too sure which is which. That’s what makes the movie interesting.

Black Swan is not really a horror movie, but it’s more emotionally horrific than many that are. The movie hooks you, rakes the flesh of your imagination. The production design is dreamily swank. The camerawork is mobile and sometimes even frenzied. (Matthew Libatique is the cinematographer.) Cassell, Kunis and Ryder are fine, often riveting — and so, I would argue is Hershey. I was never less than entertained, and I was often more than edgy.

Ballet films sometimes seem to bring out the mad poet in some filmmakers: Ben Hecht’s eerie Specter of the Rose, for example, or Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s phantasmagorical operetta-ballet film of Offenbach’s Tales of Hoffman. The most famous (and best) of them all was Powell and Pressburger’s great, colorful, rhapsodically loony The Red Shoes, a touchstoine film for young dancers-to-be, in which Moira Shearer’s Vicky suffered too, though at the hand of the tyrannical Diaghilev-like impresario Lermontov (Anton Walbrook).

Like Red Shoes, Black Swan is a movie that seems to adore art and creativity. It also seems terrified of both, scared silly of the worlds they open up. Just like the magical red ballet shoes that carry Vicky up and over the balustrade and down to the train tracks below, Black Swan’s vision of dance and art is a dangerous one, crazily over the top. But Natalie Portman (who was doubled in some dance scenes) is often wildly impressive. Portman plays with fierce, almost trance-like fervor, letting the nightmares pull her (and us) under.

Anyway, in the end, it’s not art or artistry that drives you crazy, but the way the world ignores and treats some artists. As for the artists themselves, even the mad, selfish ones … They can also be angels, even when their hearts hide some darkness, like Nina‘s. As Black Swan rightly suggests, there’s something else to fear: the demons of ambition and jealousy — and madness — that may dwell within us, always. Waiting. Ready to pounce. To whirl. To dance.

PICK OF THE WEEK: CLASSIC

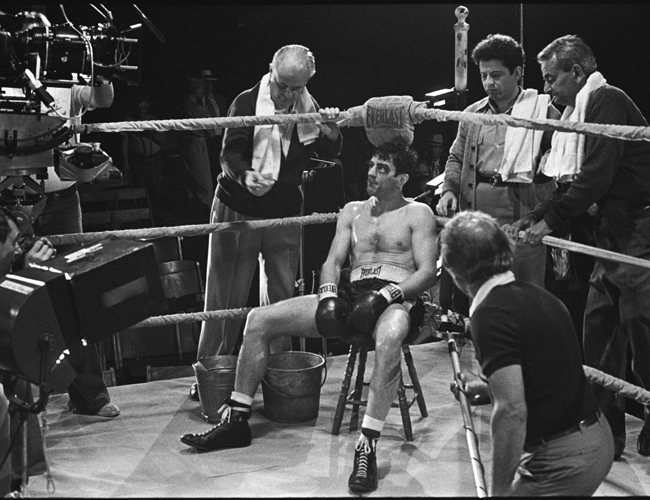

Raging Bull: 30th Anniversary Edition (Also Blu-ray) (Four Stars)

U. S.: Martin Scorsese, 1980 (MGM/20th Century Fox)

This has been out a while. But I’ve got to review it.

1950s movie lovers had, for one of their touchstones, Elia Kazan‘s On The Waterfront–a great classic film brilliantly written by Budd Schulberg, phenomenally acted by Marlon Brando, as`the slightly punchy fictional ex-boxer Terry Malloy trapped in a brutal labor struggle, memorably supported by fellow actors Eva Marie Saint, Lee J. Cobb, Karl Malden and Rod Steiger.

And 1980s film-lovers had a movie of their own, too. They had Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull, powerfully written by Paul Schrader and Mardik Martin, unforgettably acted byRobert De Niro as real-life boxer and middle weight champ Jake La Motta trapped in a brutal climb to the championship, terrifically supported by fellow actors Cathy Moriarity, Joe Pesci and Frank Vincent.

These movies are linked, vein to vein, blood to blood, heart to heart. Both were written in the vernacular of the streets: in Raging Bull’s case, such profane and dirty-mouth vernacular, so many “fucks” and “motherfuckers” and “shits,” delivered so off-handedly and almost automatically, that you probably couldn’t have played the show in a regular ‘50s movie theatre without getting arrested. Both movies were shot in black and white — incredible blacks and remarkable whites — by cinematographers Boris Kaufman (“Waterfront”) and Michael Chapman (“Bull”). Both movies had lyrical or booming symphonic/operatic scores, by Leonard Bernstein (West Side Story) for Kazan, and by Pietro Mascagni (Cavalleria Rusticana) for Scorsese.

SPOILER ALERT

Finally, the two movies all but fused into one in the last scene of Raging Bull, the scene where De Niro as the fat, washed up La Motta stares at himself in a dressing room mirror and recites Brando’s famous “Waterfront” speech: “You don’t understand! I coulda had class! I coulda been a contender! I coulda been somebody…instead of a bum which is what I am.” In that scene, De Niro’s La Motta is trying (with some difficulty) to remember his lines, and the legendary speech comes off in an almost expressionless, stumbling monotone: this speech that Brando — as he faced his crooked brother Charlie in the back seat of a Jersey taxicab — filled with so much passion, so much pain and regret, so much humanity

In Raging Bull, we follow Jake La Motta’s life the way La Motta himself told it in his book of the same title: his rise in the city and his battle to become champ, his epochal matches with Sugar Ray Robinson (Johnny Barnes), his ascension (brief, brief) to the middleweight throne, beating Edith Piaf’s lover Marcel Cerdan (Louis Raftis) for the title, and then that last fight with Sugar Ray, where Jake didn’t go down, but lost the title.

END OF SPOILER

We see also his troubled, demon-ridden, violent home life, his almost childish adoration and furious jealousy over his blonde wife Vickie, with her glossy but earthy movie star looks (played by a stunning Cathy Moriarity), and his explosive camaraderie and brainsick fights with his brother Joey (an amazing Joe Pesci). We also see the way everything begins to fall apart for Jake, when he goes crazy with jealousy and puts Joey on the floor and screams “Did you fuck my wife?”

SPOILER ALERT

Terry Malloy was never a contender, but at the end of his story, he won. Jake la Motta was the champion of the world, but at the end of his story, we see him struggling to become a facsimile of Terry the loser at his darkest moment of despair. (“You was my brother, Charley: You should’ve looked after me just a little bit…”)

END OF SPOILER

In the ’50s, most young actors wanted to be a facsimile of Terry too: to be Brando, or to beat Brando, especially in that taxicab scene. In the ’80s, before the decade went all sour and fat and greedy, a lot of them wanted to be De Niro. .(I coulda been somebody…)

And when the decade had passed and a few more years had passed as well, lots of movie people, both critics and filmmakers, decided that Raging Bull — though it had been beaten out for the 1980 Best Picture Oscar by Robert Redford’s good-hearted, well-acted, liberal family drama Ordinary People (while De Niro won Best Actor) — was really the best movie anyone had made during the ’80s, even though it was black and white, and arty, and profane, and about brutal people in a brutal world.

They were right. Raging Bull is the best of the ’80s, and of a few more decades as well. Citizen Kane is the company that Raging Bull keeps. And Casablanca and The Grapes of Wrath and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and The Godfather Trilogy and Schindler’s List. And, of course, On the Waterfront.

All black and white, except the Godfathers. All movies about the real world, or a world that seems real. All movies that can pummel you in the guts, stun you and tear your heart out.

Why is Raging Bull such a masterpiece among masterpieces? Why is Scorsese a nonpareil director, and De Niro an unmatched actor? (We hear you, Al Pacino.) Why are Terry and Jake two movie characters who live and grow and resonate in our minds as few movie characters ever can or ever will?

It’s not because of the violence and the brutality and the language, though they‘re all a part of the story and they have to be there. They’re done in Raging Bull not just to shock us or give us ugly jolts or show us how streetwise these filmmakers can be, but to reveal to us with lacerating clarity what this world and its people are really like. To show us what they go through: Jake and Vicky and Joey and Sugar Ray and all of the others, even the ones we dislike. “I was blind, but now I see,” is the movie’s last sentence, and it’s written white on black.

That’s what the film gives us most movingly. Not phony uplift. Not schmaltzy sentiment. Not tough guy posturing. Not gutter ranting. But Jake La Motta as Bobby sees him and as Marty sees him: La Motta the champ, a man who was blind, like we all are to some degree, but who now…can see. The man who chases his estranged brother Joey when he sees him in the street after years, and catches him in his arms, and hugs and kisses him with clumsy tenderness (“Charley, Charley…You was my brother…“), and who knows he was wrong, and who asks to see him again, have a drink, talk about things, be a paisano. Be his brother. Forgive him. Christ, forgive him!

Raging Bull. Best of the 1980s. A great movie. A terrible decade. Fuck that decade. You can watch Marty’s and Bobby’s picture again though, and you can see it all so clearly, why it’s great — even though there are people, filmmakers, critics, who dislike this movie still (the language maybe?) or maybe are afraid of it (the violence maybe?) or even disgusted by it (The sex, maybe? These low-life, lower-class guys, maybe?) and who think it’s overrated, that Scorsese is overrated, and that even De Niro is overrated. When I think of that…

You don’t understand, I coulda had class.

You know what? To hell with them.

Extras: Three commentaries by Scorsese, Schrader and others; Documentary Raging Bull: Fight Night; Featurettes; Cathy Moriarity with Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show; Vintage newsreel footage of Jake La Motta in the ring, defending his title.

PICK OF THE WEEK: BOX SET

The Complete Sherlock Holmes Collection (Blu-ray) (Five discs) (Three and a Half Stars)

U. S.: Various directors, 1939-46 (MPI)

None of the many screen acting teams who played master detective Sherlock Holmes and his roommate/chronicler Dr. John Watson ever nailed the parts quite the way Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce did — Rathbone, the hawk-faced, eagle-eyed, lean, brilliant and lovably arrogant Holmes; Bruce the chubby, dithering stout-fella sidekick Watson.

One might complain that Bruce was sometimes a little too chubby and dithering. (Did this bumbling, bewildered chap ever really earn a medical decree?) But Bruce’s Watson, though little like the character that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle actually wrote, was the perfect foil for Rathbone’s Holmes. And there will probably never be another Holmes to match Basil‘s, or a team to match them both. Not the admirable Jeremy Brett with David Burke or Edward Hardwicke, not Ronald Howard and H. Marion Crawford. And no, not Robert Downey, Jr. and Jude Law in Guy Ritchie’s recent Sherlock Holmes movie, though it’s an interesting try, and Downey a sometimes ingenious Holmes.

The only competition for Rathbone and Bruce, I think, is a movie team that never was, except in What’s New, Pussycat? That’s Billy Wilder’s provocative first choices for his underrated 1970 The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, Peter O’Toole as Holmes and Peter Sellers as Watson. (Wilder, of course, feuded with Sellers after Kiss Me Stupid and Sellers’ heart attack and exit, and Jeremy Brett’s buddy Robert Stephens wound up playing the part for Billy, with Colin Blakely as his Watson.)

But I‘d like to see Steve Coogan, Robin Williams or someone from Monty Python doing a schizophrenic Holmes some day , a mad master detective who, after Watson’s seeming murder by Moriarity, takes on both personalities; Watson comes back of course, and Holmes is caught between reality and schizophrenia. Works for me.

Rathbone and Bruce, though: Nobody beats them, as a pure team.

It all started at Twentieth Century Fox in 1939 (that supposed movie year of years), where Rathbone and Bruce appeared together in The Hound of the Baskervilles (Sidney Lanfield, 1939) and The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (Alfred Werker, 1939). They were both model adaptations. (See below.) But Fox never followed up on plans for a Charlie Chan-style series, especially after both films were blasted in England and by the Doyle estate, and the nonpareil movie Baker Street duo wasn’t reunited until four years later, starting in 1942, and running through 1946, for a lower-budget series at Universal.

The Universal films were almost all directed by Roy William Neill, a silent movie veteran who gives them a strong touch of noir — and, though some critics disagree, I think the series was good all the way to the end. They were all superior B Movies, well-written, well-cast and directed, but with one notable flaw.

The first two Rathbone-Bruces had been period movies, set properly in gaslit, fog-shrouded Victorian London. The later movies, probably in order to let Holmes bring down the curtain with stirring anti-Fascist speeches and tributes to the WW2 Grand Alliance, were all set contemporaneously, in the 40s. That makes them seem anachronistic today, and its really a shame the studios didn’t just continue doing Doyle stories with the perfect pair, in period. (See below.)

Still and all, Rathbone and Bruce remain transcendent, whatever the era they’re plopped into. Rathbone‘s Holmes really does seem smarter than anyone else in the room, including anybody else (say, Professor Moriarity), who might possibly drop by. And Bruce’s priceless fumbling, silly-ass bragging and doggy devotion to Holmes, though hardly According to Doyle, sets Rathbone up, and off, beautifully.

Two from Fox. Twelve from Universal. Fourteen in all. Ah, as Sherlock H. might say, the game’s afoot! In a way, all you really need for a good Sherlock Holmes movie and a good time — elementary, my dear Watson — are Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce.

The twelve Universal films are all the painstaking UCLA restorations. (They should have taken more pains over the DVD subtitles though; at one point Samuel Johnson’s very own Watson, James Boswell, is renamed “James Bosvo.”) All of the films star Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes and Nigel Bruce as Dr. John Watson.

Includes: The Hound of the Baskervilles (U.S.: Sidney Lanfield, 1939) Three and a half Stars. This very good-looking adaptation of the most popular of all the Holmes novels, puts us eerily on the foggy moors where a monster (“Mr. Holmes, they were the footprints of a gigantic hound!“) seems to be dogging the Baskerville household (including heir Richard Greene, bride-to-be Wendy Barrie, sinister servant John Carradine and the inevitable Lionel Atwill). Not all that faithful, but it’s a fine introduction and showcase for the series’ Holmes and Watson — and, incidentally for Mary Gordon as their endearing landlady Mrs. Hudson.

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (U.S.; Alfred Werker, 1939) Three and a Half Stars. Adapted not from Doyle, but from William Gillette‘s hugely popular play, with Holmes and Watson battling that archest of arch-criminals Professor Moriarity (George Zucco), while trying to save both Ida Lupino and the crown jewel collection. (I’d choose Ida.) In one delicious garden party moment, Holmes, in music hall disguise, sings and dances an Archie Rice-style version of “By the Seaside.”

Sherlock Holmes and The Voice of Terror (U.S.; John Rawlins, 1942) Three Stars. Holmes battles Nazi spies, traitors and the Hitler-loving Voice, this movie’s version of Lord Haw Haw. First of the RKO series, not based on Doyle, but with a top cast: Reginald Denny, Evelyn Ankers, Henry Daniell, Montague Love and Thomas Gomez.

Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon (U.S.; Roy William Neill, 1942) Two and a Half Stars. Holmes baffles Inspector Lestrade (Dennis Hoey) while outwitting Moriarity (Atwill this time) and fighting Nazis. Can Holmes beat Hitler? Elementary, my dear Winston. With Kaaren (sic) Verne and Holmes Herbert.

Sherlock Holmes in Washington (U.S.; Neill, 1943) Two and a Half Stars. One of the sillier, more improbable (but still enjoyable) of the modern Holmeses, finds the intrepid sleuth Sherlock and his bumbling sidekick Watson, tracking spies and microfilm. We sometimes endure a lot for the pleasure of their company. With Henry Daniell, Marjorie Lord and Zucco as Moriarity.

Sherlock Holmes Faces Death (U.S.; Neill, 1943) Three and a Half Stars. One of the Neill series‘ very best. Scary too. Based on the prime Conan Doyle story The Musgrave Ritual, a clever cipher murder mystery, it’s set in a country manor. So — if you ignore the modern references — you can imagine you’re back in gaslit Victorian times with Holmes and Watson. The cast includes Rathbone, Bruce, Halliwell Hobbes, Hoey (as Lestrade) and two later ‘50s TV mainstays: Hillary Brooke (the blonde on The Abbott and Costello Show) and Milburn Stone (Doc on Gunsmoke).

Sherlock Holmes and the Spider Woman (U.S.; Neill, 1944) Three stars. One of the series‘ best villains, Oscar-winner and future black list victim Gale Sondergaard as the smiling, murderous Spider Woman, battling wits and webs with Holmes. A good one, with Hoey as Lestrade.

The Scarlet Claw (U.S.; Neill, 1944) Three and a Half Stars. Often called the best of the Rathbone-Bruce Universal shows, and it probably is, though again it‘s original, rather than Doyle-derived. Holmes and Watson track a seeming werewolf-like monster and a string of bloody murders in foggy Canada. With Miles Mander and Ian Wolfe.

The Pearl of Death (U.S.: Neill, 1944) Three Stars. Holmes and Watson hunt for the Borgia Pearl, which is hidden in one of six busts. Based on Doyle‘s “The Six Napoleons.” With Ankers, Mander, Hoey and Rondo Hatton as “The Creeper.”

The House of Fear (U.S.: Neill, 1945) Three and a Half Stars. A houseful of eccentrics, united in a kind of tontine (whoever survives all the others gets all their insurance) are being picked off one by one, under the very noses of Holmes and Watson. A tense, ingenious variation on “The Five Orange Pips.” With Hoey, Herbert and Paul Cavanagh.

The Woman in Green (U.S.: Neill, 1945) Three Stars. Holmes hunts a serial killer who chops off fingers. Grislier than usual, but Watson is there to relieve the tension. With Daniell, Brooke and Cavanagh.

Pursuit to Algiers (U.S.; Neill, 1945) Two and a Half Stars. Holmes and Watson aboard a sea liner, guarding a royal heir. Far-fetched but fun.

Terror by Night (U.S.; Neill, 1946) Three Stars. Holmes and Watson take the train in the series’ only example of that delicious sub-genre, the railroad thriller. With Hoey and Alan Mowbray.

Dressed to Kill (U.S.; Neill, 1946) Three Stars. Holmes reveals his flirtatious side as he pursues master femme fatale criminal Patricia Morrison, in a plot involving stolen music boxes. Holmes, flirt? This one has several references to “that woman” Irene Adler of the classic Doyle tale, “A Scandal in Bohemia,” some supplied by the perhaps slightly jealous Watson.

The series ends here, partly because World War II had ended. But I think Universal missed a sure thing by not continuing the Adventures, this time transferring Holmes and Watson to their proper Victorian era. There was another problem though: Neill, an underrated director (and also the producer), died in 1946 after following up Terror By Night and Dressed to Kill with Black Angel, a nice little noir from a Cornell Woolrich novel, starring Dan Duryea and Peter Lorre. That’s a big loss. But why couldn’t someone like RKO’s literate Val Lewton have taken over the Holmes series as producer?

Anyway, I loved watching all these movies, some once again, some for the first time, some good, some not so good, but all blessed by Rathbone’s inimitable sardonic, brainy cool, Bruce’s world-class bumbling, and that perfect movie detective team’s unbeatable chemistry. Why did audiences love them, together, so much? It’s easy to see. Holmes was the cerebral superman, Watson the fubsy everyman. We all want to be Holmes, but mostly we’re Watsons, at best. (And that’s not bad.)

Anyway, as Dr. Watson says, in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, in Nigel Bruce’s grandest moment in the entire series, “Elementary, my dear Holmes.”

Extras: Six commentaries with actress Patricia Morrison and others; Interview with UCLA Film and Television Archive Preservation Officer Robert Gitt; Short sound film of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle; Photo galleries; Theatrical trailers.

Farley Granger Noir on DVD

1. Rope (U.S.: Alfred Hitchcock, 1948) Four Stars. Warners (Also in the Warners box set “Alfred Hitchcock: The Signature Collection.”)

2. They Live By Night (U.S. Nicholas Ray, 1949) Four Stars. Warners (In the Warners Box Set “Film Noir Classic Collection: Volume 4”)

3. Side Street (U.S. Anthony Mann, 1949) Three Stars. Warners (In the Warners Box Set “Film Noir Classic Collection: Volume 4”)

4. Strangers on a Train (U.S.: Alfred Hitchcock, 1951) Four Stars. Warners (Also in the Warners box set “Alfred Hitchcock: The Signature Collection.”)

Very helpful post man, thanks for the info.