By Mike Wilmington Wilmington@moviecitynews.com

Wilmington on DVD, Picks of the Week: The King’s Speech, Le Cercle Rouge, Legends: Bette Davis

x

PICK OF THE WEEK: NEW

The King’s Speech (Also Blu-ray) (Four Stars)

U. K.: Tom Hooper, 2010

The King’s Speech — which tells the story of King George VI’s chronic speech impediment, and of how he overcame it with the help of a boisterous Australian actor/therapist just in time to help Britain win World War II — was, of course, this year’s “Best Picture” Oscar winner. And that makes sense, even though it wasn’t the movie I’d have voted for. (My favorite was True Grit.)

But this highly polished, highly entertaining British period drama from the Brothers Weinstein definitely has “class act” credentials. It’s well-written (by 71-year-old David Seidler, who also scripted Tucker: A Man and His Dream for Francis Coppola), well-directed (by Tom Hooper, British helmer of the recent PBS John Adams), and extremely well-acted by the usual top-notch British cast — especially by the three leads, Colin Firth (as the introverted, microphone-shy Duke of York and eventually, George VI), Geoffrey Rush (as his rowdily eccentric therapist, Lionel Logue), and by Helena Bonham-Carter, as Elizabeth, the future, much-beloved late Queen Mother of today’s Queen Elizabeth.

Just as important, The King‘s Speech has that look and stamp of class — of quality, literate, intelligent scripting, impeccable style, good politics and good intentions — that Oscar voters like to find and reward. And who could blame those same Academy voters — when many of them have to labor on total losers or super-expensive twaddle or on the latest slam-bang, script-deficient actioner, revenge thriller, horror show or sex comedy? (The joke: Some of those same cheesy-sounding movies eventually do become Hollywood classics.)

But The King‘s Speech is a movie that deserves a prize or two, just as The Hurt Locker did last year.

I know … Good intentions are what pave the road to hell. But that doesn’t mean that bad intentions, or none to speak of (except financial ones), pave the road to heaven. I have to disagree with those cymics who feel that The King’s Speech may be some kind of calculated piece of Oscar-trolling, a pompous fraud of sorts. One thing this movie clearly is not, is cynical. It’s an obviously heartfelt piece from a writer who obviously saw it as a labor of love. (Seidler, a stammerer himself, researched and planned King’s Speech for years, holding off, at her request, until the real Queen Mother died. In 2002, at 101).

The King’s Speech throbs with emotion, with full-hearted feeling, and that’s what makes it work. It carries us along with George VI’s (or Bertie‘s) anguish at his shattered speech, with the embarrassment of the Windsors, the Royal Family, including Michael (The Singing Detective) Gambon as a crusty King George V, Claire Bloom, Chaplin’s Limelight angel, as Queen Mary, and Guy (Memento) Pearce as the abdicating Edward VIII a.k.a. the Duke of Windsor), and with the tension and fear of the oncoming winds of World War II. You could call all their acting florid and unsubtle, or you could also call it bravura. It’s certainly entertaining.

SPOILER ALERT

The movie begins in 1925, with Bertie freezing up on microphone at Wembley Stadium, and ends in 1939 with his “speech,” throwing down the gauntlet to Nazi Germany and Adolf Hitler, a man — and a demagogue, tyrant and killer — who spoke very well indeed. (Insanely well.) In between, we see George V die, Edward VIII abdicate ( for “the woman he loves,” the sharkishly grinning Wallis Simpson, played by Eve Best ), Hitler’s early threats and beginning march over Europe, while Neville Chamberlain (Roger Parrott) appeases and falls, and another great speaker (and writer) Winston Churchill (Timothy Spall) rises.

END OF SPOILER

The climax of it all is the King’s speech, and the story leading up to it: the initially stormy, finally productive teacher-student relationship — and friendship — between Bertie and Lionel.

That odd comradeship has to survive seemingly almost irreconcilably opposed temperaments and classes. Bertie, despite his unnerved and unnerving stammer, has some of the toniest credentials in the Western world: the imprimatur of the British Royal family — a pedigree so lofty that you barely have to do anything to win or keep it, except be born and not make a total ass of yourself. (A hard task for some, including Edward VIII and the current Prince Charles.)

Lionel, by contrast, has no highborn family, no degree, no official seal of approval — only his (very effective) self-made, self-taught techniques and his practice as a speech doctor. Lionel isn’t even British. He’s from Australia, land of wild colonials, ex-prisoners, outlaws, the outback and cheeky characters of all kinds. Chosen by Elizabeth, he doesn’t even know at first who his client is. Later he asks that he and the future king interact on a friendly basis, call each other by their Christian names — a suggestion that at first appalls Bertie, as does Lionel‘s insistence that his student sing “Swanee River“ and swear like a bleepin’ trooper.

SPOILER ALERT

There isn’t a whole lot of suspense in whether Lionel will succeed. But still, the movie generates an achingly tense climax. And there is drama in watching these two disparate guys grow to know, respect and like each other. King‘s Speech is about the magic of words, the magic of voices, and it’s also about the importance of social imagery and public persona, especially in a class-conscious society like the old British Empire.

END OF SPOILER

But most of all, it’s about an unlikely friendship. That unlikeliness, and that genuine camaraderie, couldn’t have found two better actors to express it, then Geoffrey Rush and Colin Firth.

As a movie star of unusual activity, Rush is also an odd guy out. He looks a little like an Australian Bogie, but slightly homelier, and he projects more raw, sparking, high voltage brain power than almost any of his contemporaries. (If he sat down at a movie chess table with Anthony Hopkins or Jack Nicholson, you’d still bet on Australia.)

Rush’s forte — from David Helfgott in Shine to the Marquis de Sade in Quills, to Lionel in King’s Speech is that he can play geniuses — even obnoxious, eccentric ones — convincingly. And Lionel is both genius and eccentric, which is what makes him such a live wire on screen, and such a perfect contrast to Firth‘s royal wallflower George VI.

If Rush is a great movie eccentric/intellectual, Firth remains one of the most affecting contemporary British leading men romantics, scoring on screen again and again, from either sexual preference, from 1984’s stage to screen Another Country on. (There he played the straight student radical opposite Rupert Everett‘s gay rebel.) Even against the formidable challenge of Laurence Olivier in the 1940 MGM movie of Jane Austen‘s Pride and Prejudice, most audiences consider Firth‘s Darcy in the 1995 BBC Simon Langton version of Pride, the role‘s perfect player, with Firth’s dark-tempered gentleman sternly and believably winning the heart of Jennifer Ehle‘s Elizabeth Bennet. (Ehle is in King’s Speech too, playing Lionel‘s hardy wife, Myrtle Logue.)

Working with Rush and Bonham-Carter, Firth shows again how terrific he is at expressing repressed longing — and that trait clashes brilliantly with Rush‘s Lionel, who doesn’t repress anything.

Tom Hooper, the director here, made the Peter Morgan-scripted sports bio-drama The Damned United; last year (with Michael Sheen and Spall), and he also directed the celebrated John Adams miniseries, with Paul Giamatti, and a fine, long TV adaptation of George Eliot‘s Daniel Deronda. His ascension here is another example of what a fertile seedbed British TV is — since the British are not at all shy, as we Americans sometimes are, about adapting their best literature, classic and popular, for TV.

Hooper’s work with the actors seems flawless, and not just because he has such a great cast. His visual style is a little reminiscent of John Frankenheimer crossed with, say, Nicholas Hytner. The frames are constricted, edgily compact, but the camera (Danny Cohen is the cinematographer) is often mobile, and swift, tracking and picking up pictures and people on the prowl.

In a way, The King’s Speech surprised me. I’m not that sympathetic to the problems of Royal families, and I think we spend too much time worrying about them, especially the Windsors. For me, it wasn‘t so much the voice of George VI (reading, probably, other people‘s words) that rallied his kingdom, his “subjects.” It was Winston Churchill whose eloquence, way with words and burnished timbre inspired the British — and Churchill is played here, almost as an afterthought or cheerer-on, by Spall. Shouldn’t we have got more of his speechifying too, to hear the tradition Bertie had to live up to?

Still and all, the important thing about The King’s Speech is that, in it, we see the dramatized Churchill, we see George VI, we see the king, and we see the man behind the throne, the teacher behind the voice, Lionel. The movie, thanks largely to Rush and Firth and the sparks of language they strike together, becomes an ode to expression and friendship and the English language, and to the power of the human voice, in the right hands.

Extras: Commentary with Tom Hooper; Featurettes; Interview with Hooper, Firth and other cast members; Speeches by the real King George VI; Real Lionel Logue highlights.

PICK OF THE WEEKS: CLASSIC

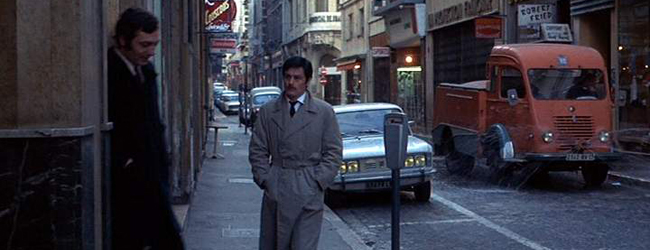

Le Cercle Rouge ( Blu-ray, Also available on DVD) (Four Stars)

France: Jean-Pierre Melville, 1970 (Criterion Collection)

Jean-Pierre Melville (1917-1973) was, in some ways, the Vermeer of the heist movie. A master of classic French film noir — and of neo-noir as well — as well as a lifelong devotee of American cinema, and especially of heist movies like John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle and Robert Wise’s Odds Against Tomorrow, Melville was a cool, sure-fingered expert at all the on-screen details and fine points of separating casinos from their winnings, jewelry stores from their jewelry, gangsters from their lives and armored cars from their loot.

He was also an immaculate artist. Like Vermeer, he had an eye for the human physiognomy and for the physical world, and he put his heart into every line. Like Vermeer, his pictures were deceptively simple and utterly haunting, punctilious and mysterious — and, like Vermeer he didn’t leave many behind him.

One of the greatest of all Melville’s films, with one of his most spectacular heists, is Le Cercle Rouge, made three years before his death: a classic neo-noir which has, as its centerpiece, a long, wordless, spine-chilling depiction of a jewel robbery in the Place Vendome in Paris. The job is pulled off with rare skill by three strangely honorable thieves, played by three great international film stars of the period: ex-convict Corey (played by Alain Delon), escaped prisoner Vogel (Gian Maria Volonte) and ex-cop Jansen (Yves Montand).

The movie, a prototypical heist thriller, is about how these three come together, how they execute the robbery, and how they’re finally driven apart — largely through the quiet skill and determination of their deceptively lumpish, bourgeois-looking but relentless police antagonist, Captain Mattei, played by the international movie comedy star, Andre Bourvil (often known simply as “Bourvil”).

Captain Mattei, a mild-looking man who lives alone with three cats, has the face of a sad clown. (He’d be an “Auguste“ in the lexicon of Fellini‘s I Clowns.) He is obsessed with finding Volonte’s Vogel — who slipped out of handcuffs and escaped from a speeding train where the two men, cop and convict, were sharing a sleeper car. Mattei is humiliated. The broken handcuffs become a psychological link.

Despite being tracked in a huge manhunt through the fields, forest and a river Vogel slips again through the dragnet thanks to a seemingly fortuitous accident. By chance, he hides in the trunk of the car belonging to Delon’s Corey, who sees Vogel secreting himself, and deliberately helps him break through the police cordon. Corey, recently released from jail himself and also a recent killer (of two torpedoes), happens to need a cool customer to help with the robbery. Vogel, who almost shot Corey soon after their roadside meeting, becomes Number Two.

The third man is an old partner of Vogel’s: Montand’s Jansen, a former cop and once crack rifleman, now a seemingly hopeless alcoholic whom we first see sweating on his bed in the grip of delirium tremens and a nightmare filled with lizards and snakes. Jansen becomes Number Three. Will he crack?

Even as the trio prepares for the heist though, Captain Mattei — relentless, canny, threatened himself by brutal police superiors — remains on Vogel’s trail. And Mattei has an invaluable source, an underworld mole, in Santi (Francois Perier), a double-dealer who looks like a ferret in a suit and who owns a nightclub that seems to specialize in crooked assignations and ersatz ‘50s American movie musical numbers, set to a cool jazzy score by Eric Demarsan. (The chorus girls in those numbers are almost the only women we see in the movie, except for one faithless lover and one cigarette girl.)

Now, the clock-hands move. The trap has been set. The jewels are waiting. Melville stages each of the acts of his criminal trio’s quest and tragedy, with the dispassionate, endlessly observant eye of a scientist — or of a great artist. The three thieves and their stalker and betrayers are about to meet — in The Red Circle.

The title of Le Cercle Rouge refers to an alleged saying and story of Buddha, who supposedly draws a red circle with red chalk and explains to his students that those who are destined to cross paths, will do so within the circle, no matter what. In this movie, as in Buddha’s curious tale, Fate — perhaps like the Gestapo pursuing the French Resistance fighters in one of the other great subjects of Melville’s cinema — will encircle them, you, us. No matter what.

Melville made and released Le Cercle Rouge in 1970, one year after making his WWII French Resistance masterpiece, Army of Shadows (1969) and two years before making his last film (with his last heist), the flawed Un Flic (Dirty Money), starring Delon, Catherine Deneuve and Richard Crenna — and three years before he died. Cercle Rouge was his last masterpiece.

Let me circle back for a moment. There is one vital quality of Vermeer’s, besides his taste for the everyday, that Melville misses completely, probably never tries for: The painter’s warmth. (I admit my analogy is imperfect.) Melville’s films noirs are cold, cold, especially when cinematographer Henri Decae (of Melville’s Le Samourai) shoots them. His crooks are cool. (They speak little and tend to wear raincoats and fedoras and to smoke cigarettes, like Bogie.) His cops are icy. His world is dark: noir to the brim. His stories chill the soul and cool down the blood, while the heart beats on.

Why was Melville so obsessed with criminals, with heists and with heist movies? Maybe because the tense, dangerous, encircled underworld of robbery noirs reminded him of the tense, dangerous encircled world of The French Resistance, in which he had fought during the war. And maybe — as with Bourvil’s Captain Mattei, the only character in the film who looks a bit like Melville (though not one of the characters whom he loves) — it’s because of the one that got away.

In the ’50s, Melville was hired to direct the movie that eventually became one of the greatest and most enduringly popular of all heist movies (the young Francois Truffaut’s choice as the greatest of all film noirs), 1955’s Rififi. Melville was later fired and replaced by Jules Dassin, who chivalrously refused to take the job without Melville‘s consent (which Melville gave).

So Melville — whose real name was Jean-Pierre Grumbach and who took his nom de plume from his favorite American novelist — almost certainly felt that he’d been robbed. He spent a good part of the rest of his career, making mostly heist or semi-heist or gangster movies now and then, and endowing them with the perfect calm artistry of an art filmmaker, a Robert Bresson (Diary of a Country Priest). Bob Le Flambeur, Doulos, Le Deuxieme Souffle, Le Cercle Rouge — all classics, with melancholy scenes somewhat reminiscent of the doom-haunted Rififi and its long, virtuosic, wordless robbery scene and its dark, bloody ending.

Melville made Le Cercle Rouge in 1970 and it was cut, against his wishes. (This Criterion DVD has the complete, restored 140-minute director’s version.) Three years later, at 55, he was dead, Now, although Delon is still alive, the moviemaker and his cast are an army of shadows. Volonte is dead, Montand is dead, Bourvil is dead. Perier is dead. And Jules Dassin, who made Rififi, is dead as well, as is Truffaut. So probably are all the American film directors — like Huston and Wyler and Wise — whom Grumbach/Melville loved. So is almost everyone who fought in the French Resistance.

Such is life, of course. And such is film noir. As Buddha said, when you have an appointment within the red circle, it will happen. No matter what. (In French, with English subtitles.)

Extras: Excerpts from the “Cineastes de Notre Temps” French TV program on Melville; On-set and archival footage, including interviews with Melville, Delon, Montand and Bourvil; Video interviews with critic/Melville expert Rui Nogueira and Melville’s assistant director Bernard Stora; Trailers; Booklet with essays by Michael Sragow and Chris Fujiwara; interview with composer Demarsan; Excerpts from Nogueira’s book-length interview Melville on Melville; An appreciation of Melville by director John Woo.

PICK OF THE WEEK: BOX SET

Greatest Classic Legends: Bette Davis (Two Discs) (Four Stars)

U.S.: Various Directors, 1938-43 (TCM/Warner Brothers)

Bette Davis: What a dame. She was one of the inarguable Hollywood immortals. She was also a female movie superstar with great range, one of the few who could evolve in her very long career through so many changes: from bad girl to glamour queen to Oscar goddess to thriller-movie gargoyle to revered elderly legend, and yet never sacrifice most of her audience’s sympathy. Not even when she reared back in Beyond the Forest, assumed a saucy, frosty stance, swept the house with a contemptuous gaze and snorted “What a Dump!“ — the famous opening line in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? put by Edward Albee in the vitriolic mouth of Martha, a character otherwise inspired by bad-tempered independent filmmaker Marie Menken.

What a dump. At times that seems Bette’s indictment of the whole overblown, trash-happy Hollywood system that she battled for decades (especially when she was the discontent, dissident queen of the Warners lot), to get better roles, a better shake, better movies.

She had to fight. She did fight. Always. Bring on Jack Warner. Bring them all on. After a flotilla of early ‘30s potboilers, in which she and other gifted but often ill-used Warners contract players like Jimmy Cagney and Humphrey Bogart and Edward G. Robinson (if she was lucky) would bat and fast-talk each other around, she became an acting star in another studio‘s movie: as the sullen, slutty waitress Mildred in John Cromwell’s RKO movie from Of Human Bondage, W Somerset Maugham’s semi-autobiographical novel of his most unhappy love affair. (In real life, reportedly, “Mildred” was a sullen, slutty boy.)

That was the role for which she was denied a deserved Oscar. (1934 was the year of the big It Happened One Night sweep). But it was also probably responsible for the undeserved Oscar she got next year for the bad girl potboiler Dangerous. (Who should have got it? Maybe Bette’s great Oscar nemesis Kate Hepburn in Alice Adams.)

But Bette very richly deserved the next Oscar she got, as the scarlet women turned self-sacrificing gallant lady in Warner Brothers’ and director William Wyler‘s (and co-writer John Huston’s‘) magnificent Southern drama Jezebel — one of the films in this “Greatest Classic Legends” TCM Davis set, maybe the best movie Davis ever made, and maybe the best role she ever played.

Yes, I remember Margo Channing in All About Eve, and also all the other films in this TCM/Warners set (Dark Victory, Now Voyager and Old Acquaintance). I‘m quite partial to both Margo and Baby Jane Hudson in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? And there’s always Mildred. Or is it Eldred.

But Jezebel is the movie that the great French critic Andre Bazin insisted was, along with John Ford’s Stagecoach and Marcel Carne‘s Le Jour se Leve, one of the “perfect” films of the cinema. Watch it again here, and you’ll probably agree. Davis, Henry Fonda, Wyler and Huston and the writers, and cinematographer Ernest Haller all did achieve Hollywood perfection, or as near as you could get it in 1938 (and that was a damned good year, like the ones that immediately followed it). Jezebel is one of the movies for which she’ll always be remembered and always should be remembered — even though “Baby Jane,” 24 years later, breaks your heart in ways that it’s never been broken before or since.

Bette went on, scrapping, battling, pushing, holding her throne throughout the ‘40s, or at least trading off with Hepburn (and occasionally her other nemesis, and her future “Baby Jane” combatant Joan Crawford), pushing, slipping a little, making a spectacular comeback with All About Eve, then hanging on, working still, making other semi-spectacular comebacks and holding on almost to the end with 1987’s fine Lindsay Anderson movie drama The Whales of August with her superb costar Lillian Gish (nobody‘s nemesis and the most enduring movie actress of them all). Bette had her last movie acting credit Wicked Stepmother (an embarrassing one, but a credit nonetheless) in the year she died, 1989.

She must have loved to act. And, of course, we loved watching her.

She wasn’t ever really a glamour queen, you know. No Garbo, no Dietrich, no Carole Lombard. She could look pouty, almost plain at times. In Now Voyager, one of her signature roles, she’s a wallflower who blossoms. Even her divas make it on spunk and brains more than camera-seducing dazzle.

Still, in Jezebel and in some others, she’s beautiful. Astonishingly beautiful. It may seem a cliche to say “it comes from within,” but it does, it does.

It’s a shame she wound up at the end with all those “Nannies” and “Bunny O’Hares,“ and “Burnt Offerings.“ A shame she didn’t have a shot at Martha as the movie of “Virginia Woolf,” or maybe in a later TV film of it. In a better world, she could have been matched in a “Woolf” of some kind with her old Jezebel guy, Hank Fonda, who’d been Albee’s first choice to play George.

Or she and Kate Hepburn could have done the lead female roles in Tennessee Williams’ lyrical play Night of the Iguana, Bette in the role she played on stage, which became, in the movie, Ava Gardner’s role. Kate in Margaret Leighton’s part, which became in the movie, Deborah Kerr‘s role. But what’s more ageist than the movies or TV, especially these days? You can get crazy thinking about it.

Bette Davis had her day though. What a day!

You can see Bette in her prime (or in one of her primes, but maybe the prime of her primes) in this Warners and TCM set. It has, shiningly packaged, four of her best loved movies: Jezebel, of course, and another of her great favorites, that sublime tearjerker Dark Victory (with support from Ronald Reagan as a rich carouser and Bogie as an Irish stable master). And the matchlessly corny Now, Voyager. And Old Acquaintance, with one-time rival Miriam Hopkins as her old schoolfriend/rival, the picture which later became George Cukor‘s last movie, Rich and Famous produced by and starring Jackie Bisset, who took Bette’s’ old part, and gave Miriam Hopkins’ role to Candice Bergen.

A good package. No, a damned good package. With all the extras: Four stars. Easy.

You know, all I can say after watching all these movies again, is: It’s a damned good thing that Bette Davis, for all those years, fought for these films, fought for these roles. We who love movies will always be in her debt. (And Kate’s. And Lillian’s.) We need more Bettes: more fighters, more magnificent viragos and two-fisted mixers, more real scrappers willing to rear back and scornfully cry. “What a dump!” at all the garbage that keeps piling up.

Ah, if only we had more Bettes today: actresses battling to bring more quality and beauty and fierce snap and idealism and sparkling adult intelligence and unforgettable moments to our movies: fighting to make them better, fighting to make them good, fighting to make them great, by whatever means necessary. No question: Bette ruled.

Includes: Jezebel (U.S.: William Wyler, 1938) Four Stars. With Bette Davis, Henry Fonda, George Brent, Donald Crisp, Fay Bainter and Spring Byington. Co-Script: John Huston, from Owen Davis’ play.

Dark Victory (U.S.: Edmund Goulding, 1939) Three and a Half Stars. With Davis, George Brent, Humphrey Bogart, Geraldine Fitzgerald, Ronald Reagan and Henry Travers, Script by Casey Robinson.

Now, Voyager (U.S. Irving Rapper, 1942) Three and a Half Stars. With Davis, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Gladys Cooper, Bonita Granville and Ilka Chase. Script by Robinson, from the novel by Olive Higgins Prouty.

Old Acquaintance (U.S.: Vincent Sherman, 1943). Three Stars. With Davis, Miriam Hopkins, Gig Young, Roscoe Karns and Anne Revere. Script by John Van Druten and Lenore Coffee, from Van Druten’s play.

Extras: Commentaries by James Ursini and Paul Clinton (Dark Victory), director Vincent Sherman and Boze Hadleigh (Old Acquaintance) and Jeanine Basinger (Jezebel); Featurettes; Vintage shorts (one with Jimmy Dorsey and His orchestra) and cartoons (Including Tex Avery’s great, raunchy Swing Shift Cinderella and his Hitler-bashing Blitz Wolf and Hanna and Barbera’s Oscar-winning classical piano riff with Tom ‘n Jerry, The Cat Concerto; Scoring session music cues; Trailers.

THE KING’S SPEECH is an effective if unimpressive film that was Oscar nominated not for it’s strength’s but on account of the overall weakness of mainstream of the rest of last year’s releases. Considering the “John Adams” connection, it should have been yet another of those well-made HBO Films releases (with the exception of the casting of Timothy Spall who turned in what is without question the worst Winston Churchill ever committed to film). And Helena Bonham-Carter was entirely overpraised for a decent performance in a small role.

Nice review. However, it is the Duke of York, not the Duke of Kent, who becomes King George VI. Some fact checking would be appropriate.

Being deaf, where can I get The King’s Speech DVD with English subtitles?

The new Anchor Bay DVD release of “The King’s Speech” has English subtitles, made especially for the deaf or hearing impaired. So do many other current DVDs.

Just check with the store, video company or website first to make sure that the DVD you want has English subtitles. (Popular titles like “The King’s Speech” almost always do.) It’s a very valuable feature: Non-hearing impaired watchers can also use it to run subtitles and follow the dialogue on English language movies, while listening to a DVD commentary.

I hope this information lets you, and others, watch not only “The King’s Speech,” but many of the other movies you’ve been missing.