By Mike Wilmington Wilmington@moviecitynews.com

Wilmington on DVDs. Picks of the Week, Classic: Cul-de-sac, An Affair to Remember. New: Police, Adjective

PICK OF THE WEEK: CLASSIC

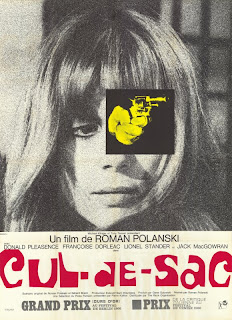

Cul-de-sac (Four Stars)

U.K.: Roman Polanski, 1966 (Criterion)

Roman Polanski’s Cul-de-Sac — one of the great English-language films of the ‘60s, a classic of neo-noir and of ’60s dark British comedy — begins with a long, still shot of a car on a road in a nearly empty landscape. The road lies under a hot-looking sky with a string of telephone poles running along the right, and on it, an old black car is being laboriously pushed by a disheveled gangster named Dickie (Lionel Stander), while his bespectacled, near-delirious partner Albie (Jack MacGowran) supposedly steers,

This opening shot seems to last forever (or at least for the length of the credits accompanied by composer Krzysztof Komeda‘s unsettling Thereminized main theme), before the car suddenly stops, and the two lost crooks will begin squabbling like a more sinister version of Laurel & Hardy, Albie bitterly complaining about the machine gun digging into his side. Both men are gunshot-wounded, escapees from some sort of botched robbery –Albie can barely movie and Dickie has one arm in a makeshift sling — and, after Albie’s inattention to his steering makes them crash into a fencepost on the car‘s left, he and Dickie quarrel for a bit (Dickie, who looks menacingly troll-like, is surprisingly tender with his dying partner), and Albie pronounces his despairing judgment on things: “Well here we are: In the shit!”

“In the shit,“ is a piece of dialogue that basically updates Laurel & Hardy’s “Here’s another fine mess.” But it would have shocked some audiences in 1966, still only a few years away from the collapse of the Production Code. And it also might well have served as another title for Cul-de-sac (The Cinematheque Française presents the director’s cut of M. Roman Polanski’s “Dans la Merde“) whose actual alternate title was “When Katelbach Comes.“ Katelbach, Cul-de-sac, Riri, Dans le Merde or whatever, it’s the film Polanski long described it as his own personal favorite among all his movies — and as highly as I esteem both Chinatown and The Pianist, I agree with him.

One reason that I was initially unimpressed with the director’s recent, excellent and highly praised The Ghost Writer, is because I thought it fell so far short of his 1966 classic, and I‘ve been waiting for another Cul-de-sac from Polanski for the last 45 years. Sometimes he comes close –as he did in The Tenant — but the death of Gerard Brach, his writing partner on both of those films, along with shifts within the film industry and in Polanski‘s life, may mean he’ll never make it.

Well, shit. But we’ve still got the old Cul-de-sac: a unique and mesmerizing film that doesn’t contain a single boring moment or one unexciting frame. Cul-de-sac goes from that seeming blind alley of an opening, shot on Holy Island or Lindisfarne, to introduce Dickie and us to the main inhabitants of the bizarre area the two hapless robber/fugitives have stumbled onto — on a little-traveled road that will soon be covered with water and cut off from the Northwestern mainland. Those Holy Island denizens they’ll meet, trapped in a sadomasochistic dead end of a marriage, and living in an ancient castle that suggests “Rob Roy” as seen by Kubrick or Bergman, are bald, timid retiree George (Donald Pleasence), and his promiscuous French wife Teresa — played by Francoise Dorleac, Catherine Deneuve’s just-as-beautiful older sister.

Albie’s imminent exit seems to leave George, Teresa and Dickie as the main or only characters in this bleak island-scape, the strangest of strange movie triangles, and for much of the movie they are — though for a brief interlude they are joined by George’s nosey, irritating and phonily cheerful visitors (Geoffrey Sumner and Renee Houston), their randy son Christopher (Iain Quarrier), one of Teresa‘s lovers, and a posh group that includes the young, silent but irresistible Jackie Bisset.

But the triangle doesn’t play out in any of the usual ways. When Dickie first sees the married couple, George has been teased by his wife into dressing up as a lipstick-smeared, falsetto-voiced big baby, an almost complete demasculinization of her already tenuously virile husband. Dickie seems to have no interest in Teresa, whom he treats like — well — shit, concentrating instead on contacting his boss Katelbach and engineering a getaway: a plan Katelbach, whom we neither see nor hear, seems increasingly uninterested in aiding. And Teresa, a sexy hellion, who looks like a divinely sexy angel and acts like a mischievous child, simply tries to manipulate everyone to her ends, which in the case of the males (excepting Dickie), she can.

Polanski and Brach pitch all this as comedy, but comedy of the darker Billy Wilder or Coen Brothers kind, full of seemingly cynical amusement at the foibles and follies and dead-ends of life. Dickie‘s situation is a dangerous one — and so are George‘s and Teresa’s — but they rarely register the reactions we’d expect. They act childishly, destructively, and self-destructively. George is attracted to Dickie‘s dour resilience and sour self-confidence. Teresa keeps cutting up, even with loaded guns. And Dickie keeps pinning his hopes on a man, Katelbach, who won’t return calls and who, like Samuel Beckett‘s Godot, seems otherwise engaged.

I mention Billy Wilder (we all should), but the true antecedents of Cul-de-sac’s script are the critically-lauded international playwrights of the ‘50s-‘60s Theater of the Absurd: Harold Pinter (writer of “The Caretaker,” which had starred Pleasence), Eugene Ionesco (“Rhinoceros,” which had co-starred Olivier and Welles), maybe Edward Albee and especially Beckett — whose most famous play “Waiting for Godot” (which had starred MacGowran), had been a dream project of Polanski’s. (He had tried unsuccessfully to buy the rights and Beckett refused, thought there are in fact a number of fine telefilms of his plays, some starring MacGowran or Billie Whitelaw.)

The Theater of the Absurd, one of the least sentimental of all theatrical genres, posited a world empty of meaning, a world without God, without solace, without much of what we call humanity, in which everything had been stripped to an essential bleakness, in which communication (and love) was almost always ridiculous and foredoomed, and every quest led, absurdly, to another blind alley.

That’s what Polanski shows us in Cul-de-sac: the Absurd, turned into black comedy and lyrical horror. But, if his people lack heroism and sympathy and humanity (except in a weird way, Dickie), the black-and-white visuals of the movie are so powerful, they endow the humans set against them with something like humanity and with a near medieval bulk and authority: unstoppable Dickie, insatiable Teresa and unhappy George. (The stunning photography of Cul-de-sac is by Gilbert Taylor, in the peak period when he also shot A Hard Day’s Night for Dick Lester, Dr. Strangelove for Kubrick, and Polanski‘s Repulsion). Polanski sets it all against the stony remnants of an old world of faith and tyranny (the castle on Holy Island), on a world cut off from the mainland (but not always), with a dance of not-quite-love and death among three desperately incompatible people: the mousy husband, his gorgeous sluttish wife and the brutal gangster, looking for a way out.

The actors in Cul-de-Sac apparently didn’t get along, at least according to David Thompson. Pleasence was an odd man out. Stander intensely disliked Francoise Dorleac. And everybody hated Stander — who, after duty as a star character actor in ’30s classics like Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and the 1937 A Star is Born was just emerging, bumptiously, from a long period on the black list.

Stander later became a character star on TV (“Hart to Hart”) and Pleasence went on to a long, lucrative Hollywood career, as the James Bond series’ Blofeld and, most prominently, as the nervous psychiatrist in the Halloween series. Francois Dorleac died in a car crash the next year, after making one more movie, with her sister Catherine, The Young Girl of Rochefort. (You may mourn the loss when you watch her.) Gil Taylor went on to photograph Star Wars. None of them were ever better than they were in Cul-de-sac — though I’m fond of Dorleac’s goofy girlfriend in DeBroca’s That Man from Rio and her mistress in Truffaut‘s The Soft Skin, and of course, of Pleasence as the bad old man in the movie of Pinter‘s The Caretaker.

These three do, indeed, seem to dislike each other. But that anti-chemistry, that tension and friction, feed reality into the performances, which are jarring and unsettling in just the right ways. The characters and the film suggest that life is a dark joke and that human bonds are illusory, and that anyway, the tide is going to keep cutting us off from the mainland every night no matter what we do.

Meanwhile, Polanski’s amazing camera eye (subjective and eerie) and his sense of the macabre, awful underpinnings of our lives — fitting maybe for a WW2 Jewish child orphan who lived by his wits after escaping from the Krakow ghetto of Schindler‘s List — endow Cul-de-sac with qualities, visual and dramatic and even philosophical, that flawlessly recall the dark side of the ’60s, of the British class system, and of life.

Polanski never filmed “Waiting for Godot” — though he still could. But he did make his “Waiting for Katelbach,” and maybe that’s better. His great nerve-fraying film Cul-de-sac, good as it was almost a half-century ago, still can stun us, still begins and ends with a blind alley: Dickie and Albie on the road to nowhere, George perched gargoyle-like, on a rock, as night falls. A fitting image for their times and ours: three gentlemen (and a lady) in deep shit.

Extras: The 2003 “Making of” documentary Two Gangsters and an Island, with interviews with Polanski, Taylor and producer Gene Gutowski; 1967 TV interview with Polanski; Trailers; Booklet with David Thompson essay.

Co-Pick: Classic

Romania; Corneliu Porumboiu, 2009 (KimStim/Zeitgeist/IFC)

The new Romanian films, of which my favorite remains Cristi Puiu’s The Death of Mr. Lazarescu, have been spare but bracing and sometimes inspiring experiences, pleasurable for their sheer cinematic simplicity, their humanistic themes, realism and cinematic austerity. This new film by Corneliu Porumboiu (1208: East of Bucharest) is no exception: the ultra-minimalist but weirdly theatrical tale of a young Romanian policeman (Dragos Bucor) undergoing a moral crisis over his impending bust of a teenage drug dealer. The cop’s problems are complicated, but they’re handled semantically. This may be one of the only films where a dramatic impasse is busted by a dictionary.

Helpful information. Lucky me I discovered your site by accident, and I am shocked why this accident didn’t came about earlier! I bookmarked it.