By Mike Wilmington Wilmington@moviecitynews.com

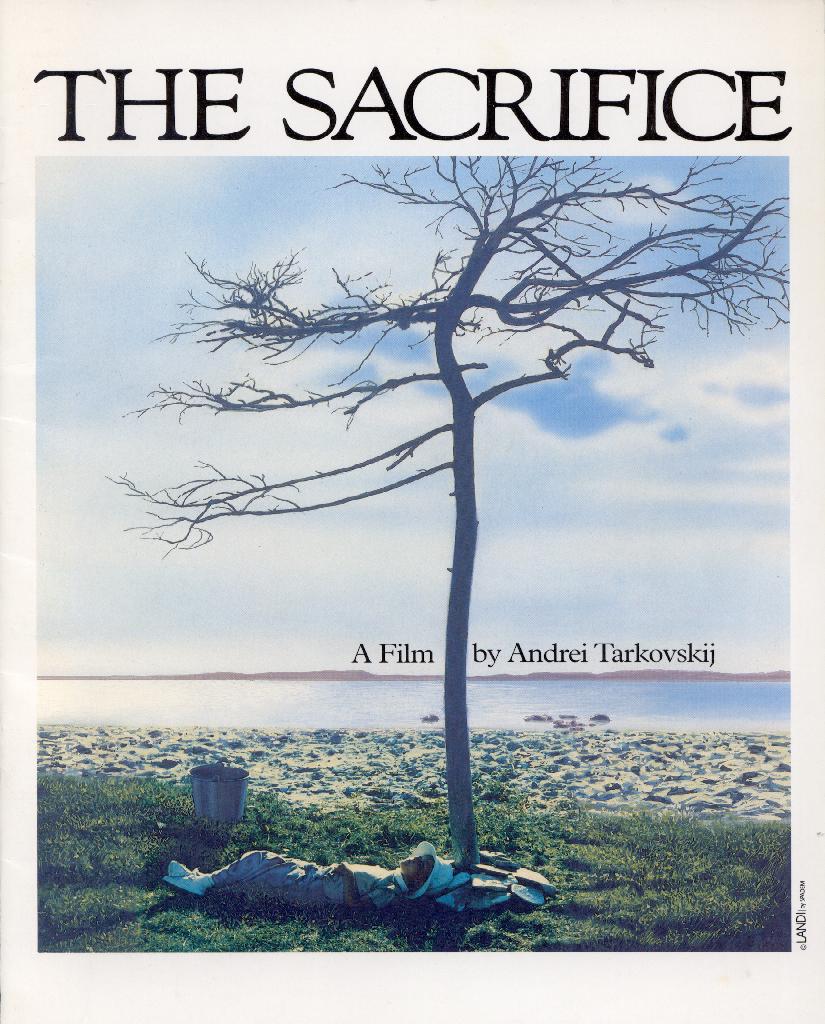

Wilmington on DVDs. Pick of the Week: Classics. The Sacrifice/Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky

Four Stars

Sweden: Andrei Tarkovsky, 1986 (Kino/Kino Lorber)

In the mid-1980s, Andrei Tarkovsky, the greatest Russian cinema artist of the post-war era, traveled to Sweden to make what proved to be his last film, The Sacrifice.

He was only in his 50s when he went to Sweden, but Tarkovsky, son of the famous Russian Poet Arseny Tarkovsky, had already scaled the heights of world cinema, while becoming increasingly alienated from the values and politics of his homeland, the Soviet Union. Despite those difficulties, he had managed, since his directorial debut in 1962 with Ivan’s Childhood — the film that won the top prize, the Golden Lion, at that year’s Venice Film Festival — to make some of the most profound and beautiful movies in the history of cinema, and to make them almost without compromise.

The Sacrifice (Offret) (1986), is one of his masterpieces, and together with the semi-autobiographical The Mirror (1976), it’s one of his most personal, heartfelt works. Yet, like all his work, it’s difficult. You need to bring something to this film, to make a kind of sacrifice yourself.

The rewards are well worth it. Made on a Swedish island, with a cast and crew drawn partly from Ingmar Bergman‘s regular film company and repertory troupe, this extraordinary work is a hypnotic, lovingly wrought drama of an artist (Erland Josephson as the writer and actor Alexander) who stares into the abyss and tries to stave off death: a man who may be mad, but who may also be sacrificing himself and what he loves most to save the world and his family from destruction.

The film’s biggest action scene is the burning of a house, shown almost completely in one take, without editing (the last scene Tarkovsky ever shot). And its most sublime moments involve the planting of a Japanese tree, an act accompanied by the celestial harmonies of Bach‘s “St. Matthew Passion.”

Bach and Bergman (and later, Da Vinci) are fitting inspirations here. The Sacrifice, like many of Bergman’s ‘60s-’70s works, is a chamber drama-film, and it takes place over the course of a day, a night and a morning. It begins and ends with images, bathed in crystalline light, of that tree, which is being planted near a Swedish shoreline, by Alexander and his child, a small boy nicknamed Little Man (Tommy Kjellqvist). Their idyll is interrupted by the eccentric postman Otto (the wonderful Bergman actor Allan Edwall, the sexton in Winter Light) who muses on life and drives his bike around them in circles, as they walk.

Then they join Alexander‘s troubled household at his isolated home, a group which includes his British actress wife Adelaide (Susan Fleetwood), his doctor, Victor, with whom Adelaide is in love (played by Sven Wolter, later the Alzheimer’s-stricken composer in Bille August’s A Song for Martin), Alexander‘s daughter Julia (Valerie Mairesse), and the servants Marta (Filippa Franzen) and Maria (Gudrun Gisladottir), whom Otto insists is a witch.

It’s Alexander’s birthday, and the family and guests take the occasion to muse on his withdrawal from life. Now a writer, he gave up a stellar acting career after scoring his two greatest triumphs, as Shakespeare‘s Richard, and as Prince Myshkin in a stage version of Dostoyevsky’s “The Idiot.” As they argue about the wisdom of his decision, Alexander reacts with an almost eerie calm, as wrapped up in his relationship with his child, Little Man, as Tarkovsky was with his own son, Andriosha, to whom The Sacrifice is dedicated.

Sometime toward the end of the light of the day, the TV and radio become full of alarm and tumult, and we and the characters learn that World War III is underway, and that nuclear apocalypse may be imminent. We don’t see any of this, except for distant TV images we can barely make out, but we don’t doubt (at first) that it’s true. Some of the people crack; some don’t. Alexander, alone, falls on his knees in the darkness in agonized prayer and promises God that he will make great personal sacrifices, giving up his family and his world, if God will turn back the clock to before the attack, and stop the war.

This is Alexander‘s dark night of the soul. This is The Sacrifice of the title. And the next day, something remarkable happens.

Like almost all Tarkovsky’s work, The Sacrifice breaks many commercial and artistic rules. It‘s a sometimes excruciatingly slow movie composed of elegant long takes that go on and on. (The movie’s opening shot is over nine minutes long, and the burning house scene lasts more than six; many shots in Hollywood movies, by contrast, last only seconds.) It has a soundtrack full of silence and Johann Sebastian Bach (as well as Japanese flute music and Swedish folk chants), and a fictional world populated by enigmatic people who talk sparely, but with unusual intelligence and deliberation, and who move and speak and ride bicycles as if they had all the time in the world — which, as it turns out, they may not. Neither did Tarkovsky, who was dying of cancer when he made The Sacrifice.

Two of Tarkovsky’s films — Solaris and Stalker — are adaptations (not necessarily faithful) of science fiction novels by the famous genre writers Stanislaw Lem and the Strugatsky Brothers, and The Sacrifice itself is somewhat reminiscent of an extended “Twilight Zone” episode. It’s the type of story you suspect might have appealed to Rod Serling, though Serling probably would have made the material leaner, more economical, less religious, more political, more of a nightmare: full of shadowy dread and topical satire. (And the larger audience probably would have preferred all that.)

Tarkovsky instead endows his movie with a mystical, rapt, deeply religious quality, at one point following Alexander‘s eyes as, entranced, he peruses a book of old religious paintings. Later, the film continuously returns to another book page, sometimes underwater, of a Leonardo Da Vinci reproduction. (All that religious art, of course, reminds us of Tarkovsky’s most admired film, the 1966 epic biographical drama of religious icon painter Andrei Rublev.)

The Sacrifice is also the kind of art film that smart-alecs like to ridicule — as if the very idea of making a film that aspires toward art and tries to tackle meaningful themes and deep spiritual feelings was too absurd for words — or for images. Perhaps. Making a movie like The Sacrifice is certainly more difficult than churning out fancy trash for mercenaries, while titillating audiences and making compromise after compromise.

But trying, with passion, to make cinematic poetry, that’s not easy at all — especially if, as was the case with Tarkovsky during much of the shoot here, you’re dying of cancer as you shoot, facing death and the loss of everything you love in every scene. Like Rodin sculpting a last statue, Rembrandt in poverty finishing a last painting, Chekhov or Tolstoy in illness writing a last story or play, or Beethoven completing a last symphony (even as deafness enveloped him), Tarkovsky did finish The Sacrifice, at the end conferring with Nykvist and the others from his deathbed, before the brain tumor took him at 54.

Should we wonder? This is what Andrei Tarkovsky did all his working life. He made films, under very difficult conditions, working under a tyrannical government (The Soviet Union during the Brezhnev years) in an often doctrinaire film industry — but all the while, creating a string of motion pictures unmatched for their sheer poetry, artistic mastery and high ambition. Ivan‘s Childhood, Andrei Rublev (his greatest achievement), Solaris, The Mirror, Stalker, Nostalghia, and The Sacrifice. Few filmmakers in any country, at any time, made films as personal, or movies that probed more deeply into the spiritual dilemmas and personal quests of humanity, especially its artists, its intelligentsia, its ascetics, its soldiers, its prisoners, its visionaries. Its Tarkovskys and its Bergmans.

I met him once, interviewed him in New York City. He spoke no English, but his meanings seemed transparent. (Of course, the translator helped.) His eyes were kind, and they burned. His peers included Ingmar Bergman, of course — and they also included his other great idols and models Antonioni and Welles and Murnau and Mizoguchi.

Still, Bergman was obviously a main source of inspiration for The Sacrifice, the whole reason Tarkovsky went to Sweden — and also the conduit to Tarkovsky for two of The Sacrifice’s lead actors (Josephson and Edwall), and key collaborators, production designer Anna Asp and Bergman’s great cinematographer Sven Nykvist (as well as Bergman’s own son, and later director, Daniel, who was Nykvist’s camera-puller). The link is obvious, but it was also Bergman who called Tarkovsky “the greatest of the great,“ praising him above all their colleagues, himself included.

One can qualify or dissent here. Bergman was a far more gifted, greater, more original, writer than Tarkovsky, and a finer director of actors, but Tarkovsky was the superior image-maker, the finer cinematic painter. And here, of course, he had Bergman’s great eye, Sven Nykvist, to help him.

If film is an art, than Andrei Tarkovsky was one of its greatest artists. And The Sacrifice is one of his greatest poems. We watch it, we listen, we marvel. The tree takes root. The boy lies beneath it. The sun blazes on the water. Bach’s “St. Matthew Passion” fills the air. Life, we feel — if only for a moment, or at most, if only for the duration of a single shot — does not end with seeming death. (In Swedish and English, with English subtitles.)

Included: The documentary Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky (Sweden: Michal Leszczylowski, 1988) Three Stars. A fine, sympathetic documentary on the making of the Sacrifice, directed by that film‘s co-editor Michal Leszczylowski, with appearances by the cast of The Sacrifice, Tarkovsky, and Sven Nykvist.

There are a couple of extraordinary scenes: A record of the last scene Tarkovsky shot: the burning of the house, which had to be done twice, when the camera jammed on the first shoot. (It was Tarkovsky’s fault; he had ignored Nykvist‘s insistence on using two cameras as backup, which they did the last time.) The first time, the director is shattered. The second time, after the trouble of the added budget, a quick rebuilding of the house, and the successful retake, he is exultant. But we are sad. We know that this is the last film scene Andrei Tarkovsky will ever direct.

Extras: Galleries; Trailers.