By Mike Wilmington Wilmington@moviecitynews.com

Wilmington on Movies and DVD; Straw Dogs (Peckinpah and Lurie)

Film: Straw Dogs (Two Stars)

U. S.: Rod Lurie, 2011

DVD: Straw Dogs (Blu-ray) (Three and a half Stars)

U.S.: Sam Peckinpah, 1971 (MGM)

I. Bloody Sam

Straw Dogs, Rod Lurie‘s remake of Sam Peckinpah’s 1971 classic — with Dustin Hoffman as a Vietnam era intellectual forced to face the beast in himself and in others — is an odd blend of two different directorial sensibilities, both somewhat spellbound by machismo.

Peckinpah, who died in 1984 (at 58) after a furious, contentious, addiction-ridden career that left him old before his time, was a great Western moviemaker, and a man whose best films seethe with a roiling mixture of breath-catching beauty and eye-blasting violence that all but set your nerves afire as you watch them.

His most famous films — including his masterpiece, The Wild Bunch (1969)– were often extremely violent, but also extremely vulnerable, and that was Peckinpah’s point. He felt that most previous American action films, including most Westerns, including some that he admired, trivialized violence, cheated on its pain and chaos, and removed much of its sting, and he intended to put it all back in, with a vengeance.

He did. His movies, including Straw Dogs, but especially the later Westerns (not the stunning ode to the past Ride the High Country, but definitely Major Dundee, The Wild Bunch, The Ballad of Cable Hogue, and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid) were often graced with extraordinarily brutal-looking action set-pieces, ferocious hell-broken-loose gun battles, in which the characters when hit soared and tumbled through the air and gunfire in slow-motion, as the blood exploded from their veins in images often described as balletic — which they often, unsettlingly, were.

Those violent, vulnerable characters who died so beautifully and so painfully were often immoral ad corrupt men, outlaws or outsiders who nevertheless lived (and died) by their own special code. There were Peckinpah lawmen too — and there were women who provoked or nurtured both kinds — but those non-outlaws were just as complex, devious and often just as dangerous. Peckinpah, like Thomas Mitchell’s Doc Boone at the end of John Ford‘s Stagecoach, didn’t trust “the blessings of civilization.”

Peckinpah was also often described and damned as misogynistic, nowhere more vociferously than in Straw Dogs — which includes a controversial scene where Hoffman’s wife, played by Susan George, is gang-raped by two of the Cornish thugs who are bedeviling them. (Pauline Kael, later one of the director’s staunchest defenders, called it a “fascist work of art.”) But that charge of misogynism, while somewhat justified, misses his whole true nature. The man who made Straw Dogs always insisted that he loved women, and he probably did — though the women he liked best in his films, were often tough dames who liked and lived with violent men, and sometimes suffered for it.

There was a feminine sensitivity in Peckinpah, and an impassioned response to the lyricism of nature and humanity that belied the macho front which he used and which, by now, we can see through — just as we can see through Hemingway‘s.

In Peckinpah’s case — though he was an authentic Westerner who grew up in ranching country in California (near a mountain called Peckinpah), and whose uncle was the well-known “hanging judge” Denver Peckinpah, and who was himself a U. S. Marine in China in World War 2 — his “Bloody Sam” persona, was probably both a defense and a ploy. It was the mask he apparently used to make his movies with less interference, to try to intimidate producers or executives, and to transfix his casts and crews, to get what he wanted from them. Much of the time, he did. When he didn’t, or when he felt betrayed, he could become violent.

Rod Lurie, on the other hand, seems more of a solid citizen. His military tour was in the Army and he‘s a filmmaker who likes to make intelligent, liberal-minded political movies, with classy casts (Deterrence, The Contender, Nothing But the Truth). Before he became a writer-director, Lurie worked as a movie critic for Los Angeles Magazine and on radio — and he was a sometimes obnoxious but entertaining critic who liked to deviate at times from the critical mainstream, crack wise, say outrageous things and rile everyone up. I’ve known him for years, not all that well, but he always seems a nice, smart, movie-savvy guy in person, certainly not the self-destructive poet and lyrical troublemaker — and wild genius — Peckinpah was.

II. The Dogs

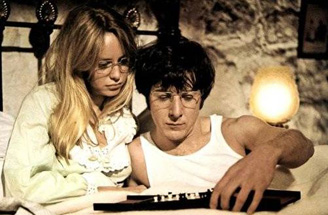

So now come Lurie’s Straw Dogs — a remake of one of Peckinpah’s biggest hits and a movie often described as among his best. (I don’t agree; I think it‘s in his second tier. But we’ll get into that later.) Peckinpah’s film, based on the novel “The Siege of Trencher’s Farm” by Gordon Williams (co-scripted by David Zelag Goodman and Peckinpah), is the story of a young American college mathematician named David Sumner (Hoffman, at the peak of his post-Graduate popularity) who has left the U. S., probably because of the Vietnam War and the turbulent campuses, and moved onto a farm, belonging to his wife‘s deceased father, in her hometown in Cornwall, England.

The wife, Amy, is played, very well, by Susan George, one of the sexy young British actress birds who thrived in the Beatle era and just afterwards, and her Amy manages to stir up sexual fevers in the local louts and layabouts who hang around the local pub — chiefly a pushy old flame of hers called Charlie (Del Henney), who can’t believe she loves this Yank wimp and tries to move in again. David, even though he can sense the electricity between them — and even though Amy warns him later — hires Charlie and his mates to help repair the roof on his farmhouse. He is an unusually foolhardy chap, dealing stupidly with unusually dangerous people.

Sex and violence are the twin engines of Peckinpah‘s movie. As Charlie and his mates work half-heartedly on the roof, almost the equivalents of the mean, half-crazy peckerwoods in a Peckinpah Western, they leer at Amy in her tight sweater and jeans, and when she complains to David, he dodges confrontation by suggesting she dress less revealingly — which annoys her and may help drive her to give the roof-repairers an eyeful in the bathroom.

The die is cast. Charlie and his gang want Amy — or Charlie wants her and most of the others are content to watch — and they are all contemptuous of David. (One of them likes “Saw” movies.) David is a semi-snob and semi-condescending college guy trying to get along with the working classes, who somehow feels he is protected by society. Amy is a hot-blooded lass, aware of her charms, who wants David to defend her, and is irritated when he doesn’t.

There’s also another Cornish bunch whom David encounters at the local pub: a rowdy crowd that includes a brutal old drunk, Tom Hedden (Peter Vaughan), the local magistrate (T. P. McKenna), mentally challenged Jeremy (played, unbilled, by David Warner) who’s aroused by the local schoolgirls, including old Tom’s daughter Janice (Sally Thomsett) — and a robust local clergyman (played by Colin Welland, who was the good teacher that same year in Ken Loach’s Kes, and would later write the Oscar-winning screenplay for Chariots of Fire). It’s a gallery that suggests, in a crazy way, a nightmare variation on John Ford’s Irish coming-home saga The Quiet Man, or a modern version of one of Thomas Hardy’s Wessex casts, with an atmosphere as charged with sex and doom as a Hardy tale.

SPOILER ALERT

And it includes that gang-rape scene, which occurs when the roof gang diverts David with a phony hunt, a macho ritual he falls for. (Strangely, Amy doesn’t tell David about the rape, in either film, and it doesn’t figure much psychologically in the movie’s climactic battle between David and Charlie’s group, something I find hard to buy.) The movie ends famously with David defending Jeremy from a seeming lynch mob after Jeremy accidentally kills Janice, and Charlie’s gang besieges the house to get him — driving pacifist David to seal up his home as if it were Night of the Living Dead, and then resort to rifles, knives, clubs and even a bear trap to defend his turf. (It’s never explained why the gang can seemingly break every window in the place and never get inside.) The movie’s last image, a deeply ambiguous one, is David’s what-the-hell smile as he drives Jeremy back to town.

END OF SPOILER

Straw Dogs is somewhat overrated and often forced, but it’s still a powerful film, clearly the work of a master. And the first thing to understand about Lurie’s adaptation is that, though (for me) it‘s flawed as well, it isn’t a cheap and sleazy job. It’s done with respect for the original — even though Lurie has transplanted the action to a macho-drenched Mississippi town called Blackwater, Mississippi and though he makes the townspeople, who mostly have the same names as the Britishers in Peckinpah’s movie, typical Deep South movie types.

Lurie turns brutal old drunk Tom into brutal ex-football coach Tom, played by James Woods with his hardest edge, in one of the movie‘s best performances. He turns Charlie into an old flame and one time local high school football star, played by Alexander Skarsgard, Swedish actor Stellan Skarsgard’s son, who gives an even better one. Lurie makes the sturdy magistrate into a sturdy black sheriff (Laz Alonso), changes David (James Marsden) into a good-natured screenwriter working on a script about the WW2 siege of Stalingrad, and turns Amy (Kate Bosworth) into a beautiful blonde actress who met David on a TV series they did together.

Despite all those switches, almost every scene in the Peckinpah Straw Dogs turns up in some way in Lurie’s version too, and most of the new characters even have the same names as their counterparts in the remake. It’s clear that Lurie knew he was adapting a movie considered by many a classic, and probably one he also admired, and that he was determined not to make the usual crass, opportunistic overhaul. (Being an ex-movie critic himself, he knew what to expect if he did — though, in some cases, he got it anyway.) Even the famous 1971 poster closeup image of Dustin Hoffman and his broken glasses has been recycled for the new movie’s poster, with Marsden.

SPOILER ALERT

Lurie has even resisted a temptation you would have thought irresistible: to clean up the movie’s controversial sexual politics and bring David and Amy together for the finale. He has made Amy more of a stand-up gal, mostly in the way Bosworth inflects her scenes. But I wouldn’t have objected to even more of a change in her temperament. I’ve always found it annoying that Amy keeps mum about the rape (why?) and that, at the end, David acts so relatively distant to the woman who went through hell with him and just helped saved his life.

END OF ALERT

But then, Peckinpah, rather confoundingly, always insisted that David was actually the villain of Straw Dogs — something that few audiences then or now perceive or take away with them, especially since Hoffman gives one of his sweeter smiles in the movie’s last shot. If he‘s the villain, who in God’s name is the hero? Is it Amy? Or isn’t there one? Admirers of Peckinpah’s movie usually say that the latter is the whole point.

III. Noon Wine

Peckinpah sometimes called his movies morality plays, and that’s what bothers me about the original Straw Dogs: the fact that many audiences still seem to take it as a morality play instead of a nightmare, with David as a hero, however dark. His complexity and bad side should be clearer, as are similar mixed personalities in other Peckinpah movies. One of the main differences between Peckinpah and Lurie as filmmakers — beyond the greater subtly or fierce spontaneity Peckinpah got from his actors — is that Peckinpah was a visual poet and Lurie’s work lacks that lyricism, at least at Sam’s intensity level. (So does almost everyone else.)

The 1971 Straw Dogs may strike me as flawed. But, like most of Peckinpah’s work, it’s beautiful in its imagery — more eerily, smokily, chillingly beautiful this time. Except for 1975’s Killer Elite, Straw Dogs may be in some ways, one of the more visually drab of all his theatrical features, and cinematographer John Coquillon gives it more of an arty-British or Eastern European visual feel. But it’s still evocatively shot, with landscapes that are poetically cheerless and gray.

Lurie’s movie, photographed by Alik Sakharov, looks a little Russian and gloomy. But, though it’s more intelligent that you think it will be going in — more sensible, and less gloriously over-the edge than the original — in the end, it’s rather commonplace, which may expose some of the faults of the first film.

Peckinpah’s enemies said that his movies were a bloody mess. They weren’t — most of them, anway. (Let’s forget Convoy and The Osterman Weekend.) The best of them showed, with great force and white hot intensity, the ways that life can be a bloody mess, and the ways that even good people, or seemingly good people, reveal their dark sides, the bad stuff that can be wrenched free from them in a crisis. Conversely, many action movies today (though not this one) are bloody messes, and that’s why the original Straw Dogs can now seem a classic, by comparison. It’s not, I think. It’s the work of an artist, but one not working at full pressure. Peckinpah’s great films are the Westerns, from the elegiac Ride the High Country (1962) to the shattered elegy Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973), and I’d include also a poignant little TV movie he made in the late ‘60s: Noon Wine, based on the Katherine Anne Porter novella.

Watching Noon Wine, you may wonder at the fact that Peckinpah could adapt so well a writer like Porter, an artist of such different personality and pitch. But Peckinpah, like John Huston, was as much a writer as a director. His favorite playwright was Tennessee Williams, and he also tried once to mount a movie of Joan Didion’s sensitive Hollywood novel “Play It As It Lays,” but his antagonists, the executives, wouldn’t let him do it. He loved John Ford, but, even more than Ford, he was influenced by the Japanese sensei (master) Akira Kurosawa. “I want to make Westerns like Kurosawa makes Westerns,” he once said, which means like Yojimbo and Seven Samurai.

How many, I wonder, of all the over-anxious young action directors who emulated Sam Peckinpah in the ’80s and afterwards, and wanted to make movies like his (I don’t include Lurie in their number), ever read much Tennessee Williams, or Katherine Anne Porter or Joan Didion, or watched many Kurosawa movies (especially the non-action Kurosawas, like Ikiru). It’s a shame in a way, that Peckinpah‘s violent persona was set so firmly in our minds by first The Wild Bunch, great as it is, and then Straw Dogs, good as it is. Bloody Sam had a lot more to give us — but it wasn’t just the booze and the cocaine that killed his heart.

Extras for the new MGM DVD: Featurettes.

(The old Criterion edition contains an excellent documentary, Sam Peckinpah: Man of Iron, a booklet with a reprinted Peckinpah interview, and video interviews with Hoffman, George and producer Daniel Melnick.)