By Kim Voynar Voynar@moviecitynews.com

Review: Daguerréotypes

“Sometimes it gives me the feeling that justifies my ‘unsuccess’. Je tiens le livre! I think the world of cinema needs people like me. We are millions, I am not the only one. They work whether they have success or not, they work on the matter of cinema, trying to understand.”

– Agnès Varda, from an interview in Sight & Sound

Agnès Varda has been one of my favorite filmmakers since the early beginnings of my own foray into seriously studying film as an art form, when I first stumbled upon Vagabond and Cleo 5 to 7. If you want to be a filmmaker yourself, regardless of what you consider your preferred genre, Varda is one of the filmmakers whose work you should absolutely make it a point to study. And if you’re already a fan of Varda’s work, you know why I say this. Much as I adore her most recent film, Beaches of Agnès, my two favorites of her body of work are The Gleaners and I (2000) and Daguerréotypes (1975).

And if you’re lucky enough to live in New York, you, oh fortunate one, will have the opportunity beginning on Monday, December 12 to see Daguerréotypes on a big screen, as it opens a run at the Maysles Cinema in its US theatrical debut. Daguerréotypes is required viewing for any Varda fan (really, for any serious student of cinema), and the opportunity to see it in a theater with an audience of other cinephiles should not be missed. Honestly, if I hadn’t just made a trip to NYC last month, I would seriously consider a weekend trip out there for the sole reason of attending a screening. That’s how much I love this film.

Daguerréotypes , like most of Varda’s films, has a rather simple premise: Varda (and until his death in 1990, her husband, filmmaker Jacques Demy) has lived on Rue Daguerre in Paris for decades. Like so much of her work, Daguerréotypes had its roots in Varda’s inquisitive nature and keen observation of things around her. Every day, she would observe the shopkeepers who ran the bevy of little independent shops on her street: the butcher, the perfumery/hosiery shop, the baker, the tailor, the accordion shop, the clock maker, plumber, the hair stylists, the driving instructor. All of these people were a part of the montage of her daily life, and she filmed Daguerréotypes by running an extension cord through the mail slot of her home, and filming only as far as she could reach with it.

Daguerréotypes , like most of Varda’s films, has a rather simple premise: Varda (and until his death in 1990, her husband, filmmaker Jacques Demy) has lived on Rue Daguerre in Paris for decades. Like so much of her work, Daguerréotypes had its roots in Varda’s inquisitive nature and keen observation of things around her. Every day, she would observe the shopkeepers who ran the bevy of little independent shops on her street: the butcher, the perfumery/hosiery shop, the baker, the tailor, the accordion shop, the clock maker, plumber, the hair stylists, the driving instructor. All of these people were a part of the montage of her daily life, and she filmed Daguerréotypes by running an extension cord through the mail slot of her home, and filming only as far as she could reach with it.

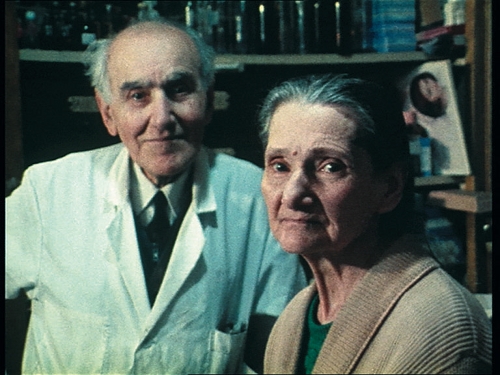

Thus Daguerréotypes encapsulates what was, in essence, the daily cinema of real life, enacted every day at her doorstep; her view of her neighbors is important not just in the purely cinematic sense, but in her ongoing interest in capturing the real and the seemingly mundane in interesting, compelling and insightful ways. And so, Varda takes us into the shops, where the shopkeepers and the customers, perhaps because she is a familiar face to them, seem remarkably off their guard. We see their day-to-day routines: the endless, slow, waiting for something to happen; the interactions with customers; the relationships between the husbands and wives, most of whom have been together for decades, as they work and live alongside each other and reminisce about how they met and fell in love in a time when a first marriage wasn’t generally considered a “trial run,” when people got married and stayed married and tried to work their way through the problems of life together. They are, each of them, the stewards of expertise in their respective professions, craftsmen of the sort that we are losing as small, family-owned shops specializing in particular things, give way more and more to warehouse stores where one size fits all.

The film’s title is in and of itself a bit of a relic for a film that captures relics, a reference both to the name of the street on which Varda lives (named after one of the inventors of the daguerréotype, Louis Daguerre) and the people Varda sees around her, which she captures in carefully framed shots that very often hail back to the kind of still, careful poses the daguerréotype process required. As we meet the people who populate the shops, we learn that most of them came to Paris from other places, and Varda narrates that “the very pavement smells of soil,” the soil of people who came from disparate places to coexist on this one little street. They coexist peacefully in part, we learn, because politics are not discussed here; politics, Varda tells us, are not good for business, and these are practical people whose livelihood depends upon keeping everyone happy.

And there is expertise here of the sort that we see less and less of today: the tailor, painstakingly sewing orders by hand, custom fit for each customer; the butcher, who wields his knife and cleaver with the ease of long practice, lovingly selecting exactly the best cut for each customer; the baker, who slides loaves of bread into the oven on a long wooden paddle with an expert flick that belies years of doing that over and over and over again; the perfume maker, who custom mixes each order for his customers, but who can also find in a moment buttons needed for a coat, or a lipstick in just the right shade; the grocer, whose shelves are carefully stacked with items within what seems a tiny space, who knows exactly where everything is, and who waits on each customer personally; and perhaps most of all, the customers, patiently awaiting their turn, knowing the same level of attention will be paid to their needs.

The best part of Daguerréotypes, for me, pertains to the fascinating bookend device of a traveling magician (all the way from the exotic land of another part of Paris!), who seems there, in part, to slyly wink an eye and remind us that all this, like life itself, is just illusion. Beneath the daily masks they wear as they ply their trades, at the end of the day they are all neighbors and ordinary people, and toward the end of the film Varda captures all these now-familiar faces gathered at a cafe to watch a show that promises to be filled with acts of “science fiction and magic.” Varda expertly uses this bit to weave a bit of her own magic, seamlessly mirroring shots of the magician’s illusions with the ways in which the shopkeepers ply their trades, showing us, as she so often has, the magic of the ordinary lives of ordinary people.

The best part of Daguerréotypes, for me, pertains to the fascinating bookend device of a traveling magician (all the way from the exotic land of another part of Paris!), who seems there, in part, to slyly wink an eye and remind us that all this, like life itself, is just illusion. Beneath the daily masks they wear as they ply their trades, at the end of the day they are all neighbors and ordinary people, and toward the end of the film Varda captures all these now-familiar faces gathered at a cafe to watch a show that promises to be filled with acts of “science fiction and magic.” Varda expertly uses this bit to weave a bit of her own magic, seamlessly mirroring shots of the magician’s illusions with the ways in which the shopkeepers ply their trades, showing us, as she so often has, the magic of the ordinary lives of ordinary people.

Varda has always seen the extraordinary in the mundane, the beauty that lies beneath the surface of people and things other people would give no more than a passing glance. Near the end of the film, she shows us the shopkeepers in a series of still, patient shots that evoke the poses one might find in early daguerréotypes: couples simply standing, side by side as they’ve stood together through decades of life, as if saying, This, now. This is life. This is beauty. Here it is, before you now. Don’t let these moments of beauty in your own life, on your own street, pass you by. Treasure them all: the man sweeping the sidewalk; the beloved wife, slipping inexorably away from the man who has loved her for so long; these people, now old and gray and in their twilight. They were once you, they were youthful and full of passion and dreams and hope; they have loved, the have lost, they have lived. Their lives, no matter how simple on the surface, have a history, a meaning, that mattered then, and matters still.

Varda has always seen the extraordinary in the mundane, the beauty that lies beneath the surface of people and things other people would give no more than a passing glance. Near the end of the film, she shows us the shopkeepers in a series of still, patient shots that evoke the poses one might find in early daguerréotypes: couples simply standing, side by side as they’ve stood together through decades of life, as if saying, This, now. This is life. This is beauty. Here it is, before you now. Don’t let these moments of beauty in your own life, on your own street, pass you by. Treasure them all: the man sweeping the sidewalk; the beloved wife, slipping inexorably away from the man who has loved her for so long; these people, now old and gray and in their twilight. They were once you, they were youthful and full of passion and dreams and hope; they have loved, the have lost, they have lived. Their lives, no matter how simple on the surface, have a history, a meaning, that mattered then, and matters still.

For me, the greatest gift of Varda as a filmmaker and an artist is not just her legacy as a founder of the New Wave, but the way in which she views life, her insatiable curiosity about the lives of others, the unflinching honesty with which she looks at the people and things that others would dismiss or discard, finding the beauty within them and through that, holding up a mirror with which we can truly see ourselves. Her insight into humanity never ceases to strike me, no matter how many times I watch her films.

All photos are credit The Cinema Guild.

Ticket information for the NYC screenings can be found at the Maysles Institute website.