By Kim Voynar Voynar@moviecitynews.com

Top Ten 2011: Notable Indies

Okay, I lied. There are actually eleven films on this list, but they all deserve a little spotlight, so I decided not to cut one of them. There are quite a few indie films on my Top Ten Narratives list, but there was a lot of work this year from independent filmmakers that I saw at festivals this year that moved me, surprised me, impressed me, or just stuck with me throughout the year. Here are the indie films that stood out from the pack for me this year (Note: this list includes films that have not yet been released in the US or picked up for distribution, so far as I know).

Alps, Giorgos Lanthimos

This brilliant follow-up to critically acclaimed Dogtooth reveals director Giorgos Lanthimos as one of the most unique and interesting new voices in cinema we’ve seen in the past few years. Lanthimos has a great gift for taking broad ideas and reducing them down to these abstract, frequently bizarre situations in which everyone taking part fails to recognize just how bizarre they are. He redefines deadpan, using his own brilliantly calibrated lens to reveal the world in a way that’s completely unique.

The Color Wheel, Alex Ross Perry

The Color Wheel, one of any number of black-and-white indies I caught this year, stood out from the pack for putting exceedingly unlikable characters in awkward situations and still making them not completely unsympathetic. It takes guts to stray from the safety of formula, which would dictate that your unlikable character has to have some likable trait, and a certain gift for writing that way to pull it off. This was a standout this year, and a director I’ll be following.

The Future, Miranda July

Miranda July has been a consistently original voice in the art and film world for years now. The Future, a whimsical tale about a pair of not-quite-grown-up late-30-somethings whose decision to adopt an injured cat turns a spotlight on their insecurities about their lives and relationships, was one of those films that people seemed to really connect with, or really dislike; I fell in the former camp. July just skewers relationship stories that revolve around loneliness, isolation, anxiety and insecurity, and her films just resonate. For all that she tends to be whimsical, there’s nothing light in the ideas she explores.

Green, Sophia Takal

Sophia Takal made a nice critical splash this year with her feature debut Green, a film about what happens to a couple (played by Kate Lyn Sheil and Lawrence Michael Levine) when a seemingly unsophisticated woman (Takal) enters the picture. Takal, who wrote, directed and stars in the experimental film, explores jealousy, envy and insecurity in relationships through a dreamy, hazy visualization of what those emotions feel like in the mind of one character growing increasingly unstable. Green never quite comes together in a satisfying way, in part because it ends rather abruptly right when you think the last act is coming, but nonetheless this film marks Ms. Takal as a talent to keep an eye on.

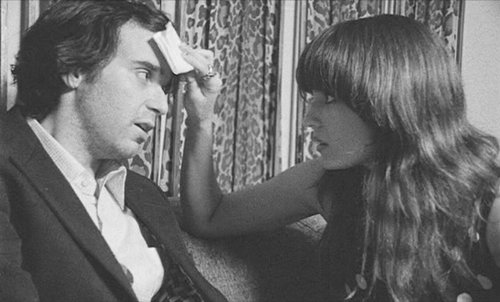

Like Crazy, Drakek Doremus

What the hell happened to all the love for Like Crazy, the darling of Sundance 2011? It just goes to show that Sundance love, like all love, can be fickle, I guess. Anton Yelchin and Felicity Jones made a huge splash in Park City with this sweet, sad story about a couple trying to sustain a long-distance relationship. I went into this film at Sundance prepared to roll my eyes at yet another Sundance rom-com, and fell for it instead. Like Crazy gets under your skin unexpectedly, and smartly sympathetic writing makes life and circumstance more the fall guy than either of its charming lead characters. Director Drake Doremus, who previously directed Douchebag (also surprisingly likable in spite of itself) is shaping up to be a unique voice to keep an eye on.

Margin Call, J.C. Chandor

J.C. Chandor’s feature debut as a writer/director made a splash at Sundance when a slew of press and industry got shut out of a packed screening. The film — which features a stellar ensemble cast including Jeremy Irons, Kevin Spacey, Stanley Tucci, Paul Bettany and Demi Moore — captures the early stages of the Wall Street meltdown inside an investment bank as the principal players begin to realize just how bad it’s going to get. A relevant, tight script which remains sympathetic to these characters without apologizing for the choices they made, and impressive, controlled direction, made Margin Call one of the must-see films of this year.

Submarine, Richard Ayode

Richard Ayoade’s feature narrative debut, Submarine, heralded one of the most original new voices in independent film this year. Adapted from a novel by Joe Dunthorne, gives us a peek into the life of Oliver Tate, an odd, logical, unemotional boy learning to fall in love for the first time as he simultaneously attempts to prevent his parents’ marriage from falling apart. Featuring striking cinematography and outstanding lead performances by Craig Roberts as Oliver and Yasmin Paige as Jordana, the prickly, morally questionable object of his affection, Submarine was one of the highlights of the year.

Terri, Azazel Jacobs

Terri may be director Azazel Jacobs’ most polished and technically proficient film yet, but he still retains the originality and vision that he brought to his early-career efforts, Momma’s Man and The Good Times Kid. The highlight of Terri is the terrific breakout performance by Jacob Wysocki in the titular role as a huge, depressed boy struggling to make it through a high school world in which he’ll never quite fit. John C. Reilly shows up as the vice principal who reaches out to the bereft, lost souls of his high school and bonds with Terri, giving him hope that his future might not be as bleak as it seems.

The Off Hours, Megan Griffiths

Megan Griffiths’ smartly directed feature about a night-shift diner waitress stuck in a life-rut evoked the setting of a lonely diner on endless long night by using methodical, patient pacing to draw the audience into the film. A solid lead performance by Amy Seimetz lent a touching poignance to a story about people at a crossroads trying to figure out the path forward. Griffiths, who landed her next feature, Eden, off the strength of The Off Hours, has been around the Seattle indie film world for many years and is finally making her mark.

The Oregonian, Calvin Reeder

By far the ballsiest, craziest experimental indie I saw all year, The Oregonian requires a certain willingness to let go of the need for convention to appreciate what director Calvin Reeder is going for. He doesn’t make it easy for you — abstract storytelling, lots of discordant noise and acid-dropping visuals are used to explore death and dying in a way that I’ve never seen done before and probably won’t see again. Truly one of the most original films of 2011. See it if you can, but go in prepared to be taken on quite a ride.

Think of Me, Bryan Wizemann

Lauren Ambrose has garnered a great deal of attention for her turn as Angela, a stressed-out, inadequate single mother struggling to keep her head above water in Think of Me, which had its world premiere at Toronto. This was a plum role for Ambrose. It requires her to convey a certain fragility, a sense of hopelessness and desperation, to make the choice facing Angela feel real and not contrived; moreover, it demands that she bring to life this young woman who we see make some stupid choices while still allowing the audience to empathize. Wizemann’s sensitive script makes you question your own prejudices; we can see how much Angela loves her daughter and wants very much to be a good mother and do right by her, even when she’s doing things that make you question her fitness to be a mother at all. It’s a layered construction of character that requires talent to pull off, and Ambrose knocks it out of the park.

SPECIAL MENTION: Short Film

Pillow, Joshua Miller and Miles Miller

I don’t usually mention short films in my end-of-year lists, but this year one short film, Pillow, was so head-and-shoulders above every other short I saw this year that it deserves a mention. Written and directed by brothers Joshua Miller and Miles Miller, Pillow breaks pretty much every rule you ever heard of for short films, and does so remarkably well. It’s 20 minutes long when most fest programmers will tell you they prefer your shorts to be no longer than eight minutes, and there’s no dialogue. At all. It’s not a silent film, exactly, but it tells its story, kind of a Southern Gothic-meets-Of Mice and Men, purely through some terrific acting by Ed Lowry and John C. Isner as a pair of brothers leading desolate, lonely lives in a desolate, lonely place, tethered to their demanding, presumably infirm, mother. The cinematography, by Gabe Mayhan, is just stunning. One of my favorite films that I saw all year.