By Kim Voynar Voynar@moviecitynews.com

Review: The Ballad of Genesis and Lady Jaye

Every now and then, I’ll watch a movie that really strikes a chord in me for one reason or another. This is one of those times, so bear with me a bit, will you?

One night when I was in ninth grade I was sleeping over with my best friend Monica, and she reverently pulled from her fairly impressive collection of LPs this Throbbing Gristle album she’d gotten from God-knows-where. This was Oklahoma circa 1982, it’s not like we were in growing up in a hot-bed of alternative music and culture. Maybe she stole it from her ex-stepdad, a very nice hippy-artsy type who smoked a lot of pot and was into art and weird music and anti-nuclear protests and nudist camps.

However Monica came to have Throbbing Gristle’s Greatest Hits LP in her possession that fall of our freshman year, we had it, and we dug it. We’d never heard anything like it, all this noise and dissonance and screeching, but also beauty; every song sounded different, and none of them sounded anything like the music our parents listened to, or the Top 40 music they played on KJ103, the bubblegum station favored by the preppy set at the Catholic high school. We were both starting to get very interested in matters of sex, drugs and rock and roll, though up to that point we’d only dipped our toes in the pool, so to speak. But 1982, now, that was the year we started pursuing matters more seriously.

Monica, who was already into reading the serious kind of books I hadn’t yet begun to really consider, had recently turned me on to Naked Lunch and Howl, and while I hadn’t quite wrapped my spinning brain around them, we both got it firmly in our heads that year that being a serious artist required experimentation with drugs and sex (not that I disagree with that even now, but at the time it was a novel concept to me …). We lived in a conservative place, although my brother and I grew up thinking everyone’s house smelled like pot and incense, and Monica’s mom and step-dad took her to nudist camps and protests for women’s rights and against nuclear anything. Perhaps being exposed to things a little outside the mainstream contributed to us being so immediately open and accepting of ideas around altered states and sexuality and gender identity. And once we latched onto exploring those ideas, we were hooked. We needed experiences. We were deep thinkers. We had big feelings.

You know how it is when you’re 14.

Monica and I liked Throbbing Gristle for the same reason we started listening to bands like the Sex Pistols and the Butthole Surfers: because their names alone sounded like something that would get you in trouble, and their music was pretty much guaranteed to make your adults say, “What the hell is THAT?” I mean, I liked Velvet Underground and the Beatles, but my parents did too, so there was no shock value, no differentiation to be found there. But Throbbing Gristle, the Ramones, the Sex Pistols, they had serious parent-stressing potential. We also got very into David Bowie and Alice Cooper, and it wasn’t long before we agreed that all these albums would sound even cooler with the help of a mind-altering substance or two. Clearly, that was what the artists would have wanted, how they intended their music to be experienced. So we tried that out, and hey, whaddya know, we liked that even better. Eventually, we moved on to Rocky Horror and got really heavily into Pink Floyd and acid trips and mushrooms, and Throbbing Gristle became less a part of our regular soundtrack. Teenagers are fickle creatures.

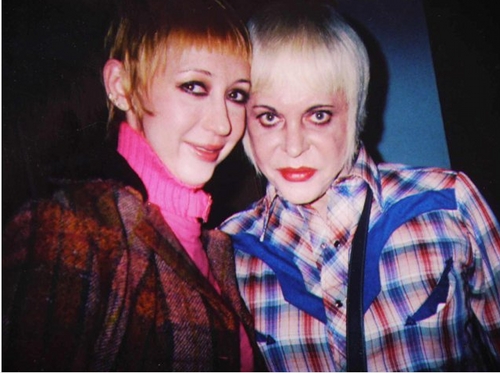

All this came back to me the other day when I watched a screener of The Ballad of Genesis and Lady Jaye, a documentary in which director Marie Losier explores the relationship between the industrial music pioneer Genesis P-Orridge (one-fourth of Throbbing Gristle) and his longtime partner in life and art, Jaye Breyer (otherwise known as Lady Jaye), who passed away in 2007. Losier skillfully interweaves photographs, home movies, interviews and footage of performances in painting this intimate portrait of Genesis, who grew up a picked-on outsider and became a rebel with a serious cause, and his/her ladylove.

It would have been easy for Losier to make a documentary focusing on the contributions of Genesis to industrial music and performance art, but she chose instead to tell the story of Genesis through the story of his/her marriage and long-term artistic partnership with Lady Jaye. The resulting film is a remarkably intimate exploration of the relationship between Genesis and Lady Jaye, whose most important performance art project together involved the pair of them delving into pandrogeny, a concept that involves a man and woman shedding away their physical (and especially gender-based) differences to merge themselves into something that’s essentially one being. Toward that end, the pair embarked on a series of surgeries, culminating in breast implant surgery on the same day, to make themselves look more and more alike. Seeing Genesis and Lady Jaye together, it’s impossible not to get how consuming and complete their love for each other was, and it’s fascinating to watch these pioneering artists explore through their own bodies and lives the artistic and philosophical concepts they espoused.

Talk about living your work.

Losier uses her film about these experimental artists as an experimental art form itself, pulling in bits and pieces from here and there, weaving in this bit of archival footage of a sound check before a show, that clip of Genesis in drag and a Hitler mustache, this bit of handheld of Genesis and Lady Jaye hanging out, with interviews with Genesis reminiscing about Lady Jaye and a life spent on the fringes of society, challenging the status quo. Genesis is proud of this body of work, and he/she should be. How many people can legitimately claim to be one of the founders of an entire genre of music, an influence on the work of the artists like Trent Reznor, and to have palled around with the likes of William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin?

But the heart of the story, which Losier never loses sight of, is the relationship Genesis and Lady Jaye had with each other. How rare is it to see a film – any film – that explores the idea of a relationship between a man and a woman that’s so deeply rooted in mutual respect and equality and trust? Losier intimately captures the heart of this remarkable pair of artists, and it’s fascinating to watch the way her roving, hand-held camera work and unconventional editing mirror the film’s subjects.

Monica committed suicide a two years after we first listened to that Throbbing Gristle album, and never had the chance to fulfill her own artistic ambitions. It’s too bad, because I think she would have done something amazingly cool with her life, if she’d lived it. But I’m grateful to Marie Losier for making this film that so intimately explores Genesis and Lady Jaye, and for stirring inside me that dormant memory of lying on the shag carpet in my best friend’s bedroom, getting my first taste of industrial music, when I was at the very beginning of starting to think about whether I might be brave enough to be an artist of some sort myself some day.