By Andrea Gronvall andreagronvall@aol.com

The Gronvall Files: PAUL WEITZ ON BEING FLYNN

Although the new Focus Features release Being Flynn is based on a true story—Nick Flynn’s acclaimed memoir, Another Bullshit Night in Suck City—director/screenwriter Paul Weitz says he sees it as “a fable about whether we’re fated to become our parents.” The story centers on a booze- and drug-addicted aspiring young writer, Nick Flynn (Paul Dano), whose path to sobriety is challenged when his long-absent father Jonathan Flynn (Robert De Niro), an alcoholic with profound delusions of grandeur about his own status as a writer, takes up residency in the homeless shelter where Nick works. Haunting both men is the memory of Jonathan’s wife and Nick’s mother, Jodi (Julianne Moore). The real-life Nick’s real-life wife Lili Taylor and Olivia Thirlby (Juno) costar. Paul Weitz (who with his brother Chris Weitz codirected American Pie and About A Boy, before going solo to helm indies like In Good Company and mainstream Hollywood fare such as Little Fockers, where he first worked with De Niro), touched down in Chicago recently to talk about his film, his stars, and his star-crossed characters.

Andrea Gronvall: To experience the full emotional impact of the end of Being Flynn, the audience first has to go through all the dark stuff early on. You had to have been thinking, how do we do structure this adaptation without losing viewers?

Paul Weitz: Something that I sometimes worry is a flaw in myself is that I can’t really extricate some sense of humor from a sense of tragedy. Anton Chekhov would write at the front of his plays “a comedy in four acts,” and then [Constantin] Stanislavski would direct them as flat-out tragedies, and Chekhov would be furious that he’s not getting laughs. In this case I know Nick Flynn feels that there’s humor in his book, even though to some degree the events are dire. I persuaded him to put his life on hold to be on the set all the time, and one great benefit of it was–aside from having somebody to tell me if something was fake or not—that he has such a distance and irony about his own experience that it was very liberating.

Nick’s a poet, and his memoir is structured in poetic fashion, weaving back and forth in time, and in styles. I took each story line—Robert De Niro’s, Paul Dano’s, and Julianne Moore’s—and chose to show the point at which they were in the most danger, then intercut between them, and had the transitions be all sound and visual. And so there’s sort of a fugue state in the movie.

AG: No way that everything in Nick’s book could fit into the movie, but why did you decide not to include Nick’s brother in the film? And why did you decide not to show the enabling aspects of Jodi’s character? I’m thinking of this passage in Nick’s memoir: “I drink to get drunk…. By the time I’m seventeen, my mother and I drink together sometimes, and sometimes she shows me the quote she keeps in her wallet–‘Never trust anyone who doesn’t drink.’”

PW: His brother, Nick told me, was somewhat uncomfortable even being included in the book, and didn’t really want to be part of what was depicted on the screen. That [decision] also made Nick’s character and situation in the movie more extreme, in that the only person who could possibly untangle this web that’s allowing him to get through his life is his father, who he has such a problematic relationship with.

In terms of the quote that you mention, I wrote versions of the script that had that in it, but I had a relatively compact amount of time to express something about the character Julianne Moore was playing. The most you see of Julianne is in flashbacks to when Nick was 10 or 11 years old. There’s only one scene where you actually see Paul Dano with her; it’s always Liam Broggy who’s playing Nick as a young boy. I thought that it would give the wrong impression to take that dialogue and transplant it to where she’s talking to an 11-year-old kid; it would make her too culpable. Because the real contradiction is that she was somebody who brought light into Nick’s life, and then succumbed to her own depressions.

AG: Let’s talk about technique. After seven years of preparation and 30 screenplay drafts you shot the picture in only 36 days. Maybe it was because of the rhythms you fell into during a fast-paced shoot, but your movie has no flab. I love how we meet the characters at the homeless shelter, where each looks into the camera and we get a quick synopsis of who they are, who they were, and who they’re going to be.

PW: You’re introduced to the people who work in the shelter in an entertaining fashion. I was trying to recreate the feeling that Nick has in going in there: that far from being a grim place to work, it’s actually exciting. It’s loaded, and dangerous, and in a certain way fun, and his heart races as he gets in there.

AG: And it gives him material.

PW: It does give him material, and during the course of this scene he’s getting the material for writing his memoir, essentially. One has a tendency to think of the people working there as being largely saintly. Some people are religious; there’s a character who says, “I want to live my life the way Christ does–and I hate my rich parents.”

AG: That got a big laugh at the screening I attended.

PW: That’s good! And then you have people who might have lived there, and who’ve gotten themselves out of it and ended up working there. The character played by Wes Studi, the wonderful Native American actor, was based on a guy who was running the van program that would go out on the streets at night–a Native American guy who moved to Boston, and at the age of 15 or 16 was an alcoholic who was living in the shelter.

AG: I also loved that quick montage showing the succession of Jodi’s boyfriends. How did you come up with that?

PW: That was an early idea I had; I like doing things without CG. Basically, the scene’s a game of catch that the preteen Nick is playing with a bunch of different boyfriends that his mother had; that was how I was going to express the idea that she dated a lot of guys. I did it all in single takes, with actors who’d claimed they could play baseball. About half of them were lying. I would pan left with the camera to the little kid and he would pitch, and these guys would be lined up, hidden on the right side of the camera, and then run on and catch the ball and throw it back. And whenever one would drop the ball, the whole crew would groan. It was a really fun, sort of 1920s-style way of shooting.

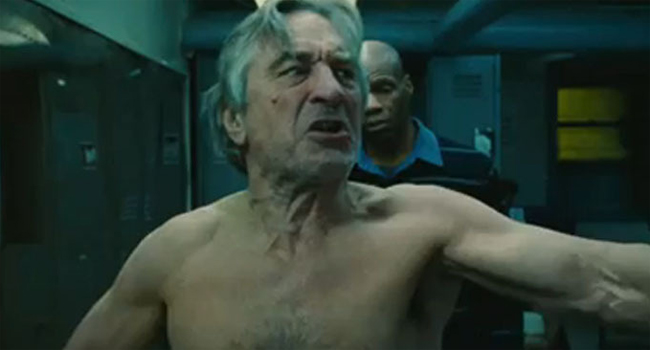

AG: Tell me about the powerful scene where Jonathan has his meltdown in the shelter’s changing room.

PW: That’s when he’s staring into the mirror, yeah? It was one of those parts of the screenplay where it just says, “Jonathan rants.” Of course you can’t hand that to an actor, so I worked with Nick Flynn on the kind of repetitive things that Jonathan Flynn would say in real life. Here he is succumbing to his demons and his delusions; in particular, he is somehow being brought face-to-face with the love of his life, Nick’s mother. And so we handed De Niro a four-page stack of essentially non sequiturs–impossible, really, to memorize. I said to him before shooting, do you want me to tell you what small portion of it I believe will end up in the movie? He said, “No, just let me shoot it as written, and then use what you want. But I’ve really been working on this.” And then I shot it from both sides, because normally you’re quite keen not to. The first couple or three films I directed I was terrified of this idea of the line, which is–

AG: It’s crossing the axis.

PW: Yeah, you scramble the viewer’s head if you jump back and forth. In this case I was consciously crossing the line in shooting it from two directions. He’s staring at himself in this funhouse mirror–which is something that existed in the actual [Boston] shelter, Pine Street, that the movie is based on.

AG: The Flynns are fascinating, but you have quite an interesting family yourself.

PW: It’s eccentric, sort of minor Hollywood royalty. My mom [Susan Kohner] was an actress, whose I guess best known performance was in the film Imitation of Life, a really marvelous melodrama. And then my grandmother [Lupita Tovar] was a Mexican film star who came to Hollywood during the silent film era, and ended up doing the Spanish-language version of Dracula (1931), which was shot by Latino actors on the same stage sets as the American versions. The Americans would do their version, and then the Latin actors would come in the middle of the night to shoot theirs. My grandfather [Paul Kohner] was working at Universal and produced, and the story I was told was that it was kind of a scheme of his to keep my grandmother in the country, because she was going back to Mexico for lack of work here.

AG: I don’t want to belabor that numerous writers have commented on your tendency to pick films about father-son relationships, but have you ever thought of doing a documentary about your dad, John Weitz?

PW: It’s really interesting, because he was formed in the crucible of World War II: being a German Jew, a refugee, and then joining the American army and the OSS. He was an extremely macho fellow who was a fairly successful racecar driver, and a fashion designer, which is not usually regarded as a particularly macho profession. But it is similar to Being Flynn in that when you’re a fashion designer, you can’t help but be in the terrain of appearances: how you’re presenting yourself, and how important that is. In Being Flynn, Robert De Niro to all intents and purposes is really hitting the skids, but through the belief and image that he has of himself as a great writer, he’s able to survive and persevere and, weirdly in some ways, come out on top. I have, in retrospect, wondered what kept me attached to this story over the seven years that I was writing drafts of it. And I think that the relationship between what we seem to be, what we’re trying to project, and what we are, is like an animal chasing its tail, [that] I feel in my life and in this film.

AF: It’s a weird balancing act, because Jonathan is definitely headed toward self-obliteration, and yet he also has a peculiar form of narcissism.

PW: No question, and the truly bizarre thing is that there’s an in-built level of irony, in that the real Jonathan Flynn never saw his masterpiece–that he was writing over the course of decades on napkins and envelope–published. But now he’s played by Robert De Niro in a movie; so, on some level, Jonathan’s delusions of greatness have been shown to be accurate.