By Mike Wilmington Wilmington@moviecitynews.com

Wilmington on DVDs. Man on a Ledge; Kill Bill, Volumes One and Two; Run for Cover; The Lawless

MAN ON A LEDGE (Also Blu-ray) (Two Stars)

U.S.: Asger Leth, 2012 (Summit Entertainment)

Man on a Ledge, a thriller about a man clinging to a 21st story hotel ledge, while Manhattan goes wild below him, is a real mind-boggler—not because of any hair-raising suspense it generates but because the story is so ridiculous that, despite the movie’s high-octane cast and technical finesse, it’s capable of plunging you into a state of continuous befuddled exasperation.

The picture’s constantly accelerating absurdities, which include a ludicrous heist scene, a egomaniacal TV newswoman exploiting the story, bickering cops and crisis managers fighting and flirting with each other (and with the jumper), and a Donald Trump-like villain sneering away—suggest the filmmakers assume their audience will swallow anything. I hope not. Man on a Ledge has that slick, self-satisfied gleam movies can get when they cost too much and they’re stuffed with formula and clichés and stars, and nobody can do anything about it. It also has a plot so preposterous, and an ending so bonkers that the only possible way to play them is for laughs, if the show were good at comedy (which it isn’t.)

The picture’s constantly accelerating absurdities, which include a ludicrous heist scene, a egomaniacal TV newswoman exploiting the story, bickering cops and crisis managers fighting and flirting with each other (and with the jumper), and a Donald Trump-like villain sneering away—suggest the filmmakers assume their audience will swallow anything. I hope not. Man on a Ledge has that slick, self-satisfied gleam movies can get when they cost too much and they’re stuffed with formula and clichés and stars, and nobody can do anything about it. It also has a plot so preposterous, and an ending so bonkers that the only possible way to play them is for laughs, if the show were good at comedy (which it isn’t.)

Consider the premise. A tough ex-cop named Nick Cassidy (played by Avatar‘s Sam Worthington), who’s in jail, framed for a $40 million diamond robbery from that Trump-like financier David Englander (Ed Harris)—escapes from custody while on a furlough to attend his father’s funeral. Then he checks into the Roosevelt Hotel, orders a room service breakfast and crawls out the window and out on the ledge, 21 stories above the streets. Soon, he attracts a crowd, as well as police (his buddy Mike played by Anthony Mackie and the cynical Jack Dougherty pkayed byEdward Burns), along with vain, callous TV news reporter Suzie Morales (Kyra Sedgwick), and a lusty but conscientious crisis negotiator, Lydia Mercer (Elizabeth Banks), who tries a little harder than cynical Jack to talk Nick back inside.

It doesn’t work. Nick keeps refusing to get off his ledge while talking in a curious accent that suggests an Australian trying to impersonate a New York City Irish-American. (Couldn’t Worthington have gotten some accent lessons from Ed Burns?) And why, you may wonder, does somebody break out of prison in order to jump out of a hotel window? Good question. (There are many more.) It turns out that what we’re watching is not a real suicide attempt at all, but an elaborate diversion, intended to preoccupy the police and everyone else, while, across the street, Nick’s live-wire brother Joey (Jamie Bell) and Joey’s hottie partner Angie (Genesis Rodriguez) break into Englander’s suite, where they’re convinced the 40 million dollar diamond is still lying around somewhere—and will exonerate Nick, if they find it. In other words, the “jump” is a phony staged as part of a robbery intended to clear the “jumper” of a conviction for another robbery of the very same diamond. Got that? You sure?

This outrageously silly heist, which Nick helps direct by cell-phone while standing on that ledge, seems twice as nutty as the one Eddie Murphy was trying to pull in Tower Heist, though that movie did have higher windows and the Macy‘s Parade as an added diversion (and no ledges). And the diamond robbery in Ledge is a heist that might have been choreographed by Jack Cole on a bad day. With Joey behind her, Angie—dressed in an outfit better suited for lap-dancing than for breaking and entering—slithers down vents and creeps around alarms to try to locate the diamond — which is not a girl’s best friend.

Why this robbery is committed during the day, after a huge crowd and oodles of police and media have been pulled into the area by the phony suicide, or why Nick didn’t do his ledge routine somewhere else further away, remains another of the show’s endless mysteries. Nor is it ever explained, at least while I was paying attention, why nobody seems to notice or wonder about Nick’s frequent cell-phone calls to Joey, while he‘s supposedly dancing around on the edge of the ledge, contemplating suicide. Meanwhile, there’s sexual tension between Burns and Banks, sexual tension between Banks and Worthington, sexual tension between Bell and Rodriguez and sexual tension between Sedgwick and the camera and between Harris and himself (just like Trump).

SPOILER ALERT

And when Nick finally does jump, in order to get to the street faster and chase Englander, it’s the most outrageous moment in a film that has all too many.

END OF SPOILER

In the early 50s, Howard Hawks was offered the script of Fourteen Hours, another movie about a man on a ledge: an actual neurotic jumper played by Richard Basehart—and the ledge guy was talked down in that movie by fatherly Paul Douglas. (Newcomers Grace Kelly and Jeff Hunter were in the crowd below.) Hawks refused the project, saying that the only way he could make a movie out of an idea like that would be to turn it into a Cary Grant comedy, with Cary as a philanderer who crawls out on the ledge to dodge his lover’s suddenly returning husband, and then, when he‘s discovered, pretends to be a would-be suicide.

In the early 50s, Howard Hawks was offered the script of Fourteen Hours, another movie about a man on a ledge: an actual neurotic jumper played by Richard Basehart—and the ledge guy was talked down in that movie by fatherly Paul Douglas. (Newcomers Grace Kelly and Jeff Hunter were in the crowd below.) Hawks refused the project, saying that the only way he could make a movie out of an idea like that would be to turn it into a Cary Grant comedy, with Cary as a philanderer who crawls out on the ledge to dodge his lover’s suddenly returning husband, and then, when he‘s discovered, pretends to be a would-be suicide.

I don’t know if that idea would have worked, though you should probably never bet against Cary Grant and Howard Hawks, especially if they got, say, Ben Hecht to write the script. But Hawks’ brief description is more entertaining, and even more believable, than anything that happens in Man on a Ledge. So is the movie that Henry Hathaway made out of Fourteen Hours.

Man on a Ledge is director Asger Leth’s first fiction feature—he’s done an admired documentary called Ghosts of Cité Soleil—and he makes the movie slick and fast. It may be ludicrous, but it’s never actually boring, and the sheer uninspired preposterousness of it all almost commands a perverse respect. Still, it’s doubtful that even Howard Hawks, or Steven Spielberg, or Orson Welles, could have done anything with Pablo F. Fenjves’ script, except bury it and start over. Fenjves has a number of feature credits, but his most interesting authorial endeavor is probably his ghost-writing of his one-time neighbor O.J. Simpson’s book, “If I Did It.” Did that experience predispose him in any way to writing about a hotel ledge ’jumper” who commits a robbery to exonerate himself from committing a robbery? Who can tell?

Extras: featurette; Trailer.

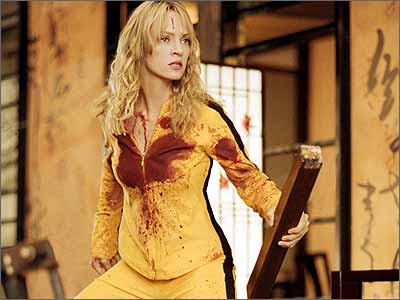

KILL BILL, VOL. ONE/ KILL BILL, VOL. TWO (Blu-ray) Three stars

U.S.; Quentin Tarantino, 2003/2004 (Lions Gate)

Quentin Tarantino’s forte is probably his mastery of tough guy dialogue; in movies like Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction (and, courtesy of Elmore Leonard, in Jackie Brown), he reaches heights of wise guy film noir grandeur. Here however he shoots a different kind of movie, with very little dialogue and an emphasis on action and visuals. Inspired by Sergio Leone, by Kurosawa‘s samurai epics and by other Asian action movies, he puts Uma (“Puma”) Thurman in the center of a wild saga of revenge and kung fu, told in two parts and featuring pungent turns by David Carradine, Michael Madsen, Sonny Chiba, Lucy Liu, Daryl Hannah, Vivica A. Fox and Michael Parks. It certainly passes the time, but I wish Q.T. would get back to crime and crosstalk some day. That’s his forte, dammit.

EXTRAS: Featurette on The Making of Kill Bill I; Kill Bill 2 Deleted scene and premiere; Trailers.

RUN FOR COVER (Three Stars)

U.S.: Nicholas Ray, 1955 (Olive)

Nicholas Ray’s Westerns — especially his masterpiece, Johnny Guitar— have a touch guy tenderness and romanticism, and a sense of torment and betrayal, that make them unique in their genre. That‘s true of Ray’s lesser-known 1955 Run for Cover, another Western made a year after Johnny Guitar, which has all of those qualities if not with the same intensity, dark humor and bizarre genre-twisting as its one-of-a-kind predecessor.

Run for Cover, like Johnny Guitar, is a dramatic fable about injustice and the people who suffer from it — victims of fate mistaken for outlaws, whom injustice makes either stronger or weaker. Based on a story by Harriett Frank, Jr. and Irving Ravetch, who wrote the revisionist Westerns Hud and Hombre for Paul Newman and Martin Ritt, and scripted by Winston Miller, who wrote the landmark cowboy film My Darling Clementine for John Ford, it’s the story of a good-hearted but embittered cowboy, movingly played by James Cagney, who served six years in prison for a crime he didn’t commit, then, after his release, gets arrested and nearly lynched for another crime he didn‘t commit (a train robbery). Meanwhile, Cagney’s young companion of brief acquaintance, John Derek, is shot and crippled for life by the posse that tracks them down.

Both these victims, lucky to be alive, are taken in by a Swedish immigrant farming family (a father and daughter played by Jean Hersholt and Viveca Lindfors), and Cagney helps nurse the young man back to (relative) health, trying also to heal Derek‘s psychic wounds, his bitterness and alienation from society (shades of kind cop Edward Platt and James Dean in Ray’s other 1955 film, Rebel Without a Cause, or, for that matter, of Derek and Humphrey Bogart in Ray‘s 1949 crime drama Knock on Any Door). Understandably, Cagney falls in love with Lindfors — and maybe, unconsciously, with Derek as well. And he‘s also hired by the local townspeople to replace the incompetent lawman (smarmy Ray Teal, the ultimate bad sheriff ), who was responsible for the miscarriage of justice.

But violence begets violence, sons rebel against their fathers (or father figures) and Run for Cover straddles to the end that knife-edge between social conscience and chaos, love and hate, that marks almost all of Ray’s work.

Cagney is marvelous. With his usual boiling screen emotions held mostly in check, and his short but powerful dancer’s frame taking over every scene, the star’s performance is also suffused with that warmth, serenity and moral strength that this great film actor could sometimes summon up, especially in his later years, belying his signature image as Hollywood’s classic mercurial gangster. The rest of the cast — including Ernest Borgnine (another Johnny Guitar vet), who plays Derek’s and Cagney’s genial, villainous tempter — act with the extra touch of humanity that was another Ray trademark.

The movie’s lyricism sometimes tips over into languor, but it’s been underrated, as was most of Ray’s film work during the ‘50s. (Except in France.) Daniel Fapp (West Side Story) photographs, in color and VistaVision; the pseudo-Frankie Laine title song, is by Howard Jackson and Jack Brooks; and the film’s striking locations include the Aztec Ruins National Monument in Aztec, New Mexico. .

THE LAWLESS (Three Stars)

U.S.: Joseph Losey, 1950 (Olive)

When Nicholas Ray was a sophomore at La Crosse Central High School, in Wisconsin, Joseph Losey was a senior. Ray said later that he came from the wrong side of the tracks and Losey from the right side — but though they didn’t mix back then, both of them became famous Hollywood movie directors (and eventually Hollywood legends and French-style auteurs), starting in the late ’40s, with classic first films (Ray’s 1949 love-on-the-run noir They Live By Night and Losey’s 1948 fable of prejudice The Boy With Green Hair ). Both of them were also political progressives, and Losey eventually fled the black list to work in Great Britain.

The Lawless — which is also known as The Dividing Line — was Losey’s second feature and the first of his admirable string of fine, tense ’50s noirs, from The Prowler to Time Without Pity and Blind Date. The writer was the great noir scenarist Daniel Mainwaring (Out of the Past, The Phenix City Story, Invasion of the Body Snatchers) — writing under his more familiar pseudonym Geoffrey Homes — and it’s a socially conscious crime and newspaper drama, set in ’50s California. Based on “Homes’” novel, “The Voice of Stephen Wilder,” the story is about a small California city that tips over into rancor between Anglo citizens and Latino migrant workers — and eventually into mob rule — when a fight breaks out between young Anglos and Chicanos at a dance, turning one of the Mexican boys (Lalo Rios) into a fugitive blamed for the death of a cop, and the flashpoint for an explosion of violence and bigotry.

In a way, The Lawless, a film about a newsman named Wilder, is the inverse of Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole; it’s about a Southwestern town plunged into madness, and a newspapermen who tries to battle rather than stoke that insanity. Macdonald Carey here plays Larry Wilder, an amiable but fiercely idealistic local newspaper editor (his paper is called The Union) trying to stand up for justice and fairness for the Mexican migrant laborers, but threatened by yellow journalism on one hand (an exploitive sob sister played by The Maltese Falcon’s Effie, Lee Patrick), and lynch fever on the other.

Gail Russell (John Wayne’s “angel” in Angel and the Badman) is surprisingly effective as a Latina fellow journalist named Sunny Garcia who wins Wilder’s heart. (So does the fugitive.) The movie mingles romance and social conscience, but in an affecting, often tough-minded way. Made with the impeccable eye, lucidity and sense of darkness that were Losey’s trademarks, it‘s influenced by both noir and neo-realism. (The evocative location cinematography is by (J.) Roy Hunt, a prolific specialist in Westerns and noir, who shot Crossfire, I Walked with a Zombie, and The Devil Thumbs a Ride.) The Lawless is an obvious precursor of 50s social and political dramas by writers like Rod Serling and Reginald Rose, but it also looks back to the Depression past, when fellow Wisconsinites Losey and Ray were young radicals in New York theater.) The cast includes John Sands, Martha Hyer, Frank Fenton, Frank Ferguson and, as one of the young town bullies, Tab Hunter. The ending, despite a touch of sentimentality, is a scorcher. You’ll know why HUAC and its pals were after Losey.