By Ray Pride Pride@moviecitynews.com

Pride’s Friday 5: August 3, 2012

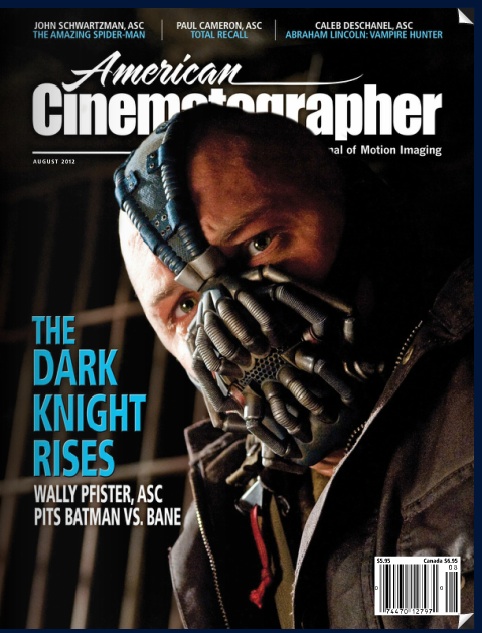

1. American Cinematographer, August 2012 issue

The latest American Cinematographer arrived Wednesday and late-night reading turned into all-night reading. A throughline linked almost every article into a narrative of cinematographers and camera crews forced to improvise as much as the most gifted actor in the abrupt conversion from cinema to digital capture, with stories of handcrafted technical problem resolution on The Dark Knight Rises, Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, The Amazing Spider-Man and Total Recall. Each piece introduces talented crews recreating on the fly camera techniques they’d learned with film, trying to keep up with untested, erratic equipment.

The latest American Cinematographer arrived Wednesday and late-night reading turned into all-night reading. A throughline linked almost every article into a narrative of cinematographers and camera crews forced to improvise as much as the most gifted actor in the abrupt conversion from cinema to digital capture, with stories of handcrafted technical problem resolution on The Dark Knight Rises, Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, The Amazing Spider-Man and Total Recall. Each piece introduces talented crews recreating on the fly camera techniques they’d learned with film, trying to keep up with untested, erratic equipment.

Panavision optical engineer Dan Sasaki even plays a recurring character (despite the primary technology for the productions coming from other sources). For The Amazing Spider-Man, AC reports he provided six sets of Ultra Prime lenses to run on three 3D rigs, which he rebuilt and matched. (The TASM article details workflow issues as well as the very, very late arrival of RED Epic cameras.) Total Recall was going to be shot as 35mm anamorphic, but then eight days before principal photography, “production decided to capture digitally with the Red Epic instead.” (35mm was used only for chase scene crash cars, presumably because those cameras are more likely to survive.) Cinematographer Paul Cameron told AC, “This was a brand-new camera I’ve never used, and we had to start shooting in eight days. It was a challenging situation.” As with most AC articles, talk turns technical but it’s never unclear to the informed film observer, especially in the appalling litany of tech jerry-rigging. “The Epic was so new that Cameron’s crew had to spend a lot of time making basic camera-support materials for it… It felt like we were going through the Industrial Revolution again,” Cameron says. “We were making base plates, rods, bracketry, follow-focus units, lens lights and handles… We had to manufacture power-distribution boxes to send out power to the tons of accessories around the camera.” And where’s Sasaki? He brought Panavision lenses to the production that were a game-saver for the production, as well as “some special ‘flare lenses,’ which were basically some of the C-Series anamorphics with little ventricular mirrors added to increase the flare characteristics.”

Sasaki also pops up in the story on The Dark Knight Rises: “In the case of the 80mm, we discarded the Imax mechanics and replaced them with a cine-style Panavision transport,” explains Sasaki. “Also, we had to rebuild the entire lens head so it could accommodate an iris mechanism, because the original Imax lens conversion did not have a variable iris mechanism.” Whew.

Caleb Deschanel’s issues on Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter were with the Alexa camera. “He had some concerns about the plan to extract a 2.39:1 image from the camera’s 16×9 Alev-III sensor. ‘We shot Killer Joe in 1.85:1, and the image held up well on the big screen because we were using most of the chip. By comparison, we had to use a smaller part of the chip to extract our widescreen image for Abraham Lincoln, and to me it looks slightly more “digital” on the big screen. Of course, the newer Alexa model allows you to shoot anamorphic with a 4×3 sensor, but that technology wasn’t available to us at the time.'” As with most issues of the magazine, the intelligence and technical savvy of every player makes for thrilling reading, but in this case, a dispiriting low as well. What’s William Goldman’s most popular aphorism? “Nobody knows anything”? (Except the camera crew.) [The ASC’s website is here.]

2. Total Recall

“Animatics” are one of the tools that can used to previsualize special effects, and watching the lightly-likable futuristic sketchbook design of Total Recall, and each of its successive action setpieces as Colin Farrell’s factory worker is thrust into a counterespionage-agent counter-reality, I felt as if Len Wiseman had directed the year’s most excellent animatic, as well as the prettiest dystopia since the first half of Wall-E. Workers commute in an overpopulated future through the core of the earth—”prepare for gravity reversal”—from Colonies sketched from the Blade Runner playbook to a cordoned United Federation of Britain, with buildings and flyways and green spaces stacked to implausible heights, as much amusing doodles as feasible structures. Like a later sequence involving elevators that move through myriad shafts both laterally and vertically, the effects are sketches, with an acquaintance with, say, Jean “Moebius” Giraud, Lebbeus Woods and M. C. Escher, among what is surely a library of others, but no great push toward adding inspiration to the neat, casually derivative basic design. [More here.]

3 The Deep Blue Sea

The great British filmmaker Terence Davies returns with a Terrence Rattigan adaptation that suggests the past is a pained place of desire, of regret and of tracking shots that are as spontaneous and unexpected as a dance number in a musical. It’s a few years after the War, and at the age of 40, Hester Collyer (Rachel Weisz, fiery, tremulous) leaves her life of privilege with her lawyer husband, Sir William Collyer (Simon Russell Beale, warm, concerned, genteelly solicitous) for passion with Freddie, a younger man, a tempestuously alcoholic ex-RAF pilot (callow, bumptious Tom Hiddleston). Bleak wallpaper and crushing emotions follow. Davies is one of the great, lyrical poets of the cinema and one of the great tragedies of film in the past couple of decades is his inability to find finance for his projects. Movies like Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988) and The Long Day Closes (1992) are filled with unforgettable images and passages that go far beyond mere drama, tactile impressions of sensations, of time passing, of time itself stopping, pausing, reflecting. Abiding sorrow is also a constant in Davies’ films, and Hester’s midlife coming to romantic awareness is both melancholy and melodrama. (In the good way.) There are moments in Davies’ work where the images pulse with color, often-rigid yet plainly magnificent compositions, and a rich use of shadow that only the greatest painters achieve on canvas. Davies admires artists like Turner and Jacob van Ruisdael, but Vermeer is his great touchstone, even in the dark reaches of The Deep Blue Sea. In an interview I had with him several years ago, Davies exclaimed, “Natural light falling through a window, there’s something ravishing about it. It’s just ravishing!” And so is his sense of the capacity of the human heart. [Video, Music Box Films.]

The great British filmmaker Terence Davies returns with a Terrence Rattigan adaptation that suggests the past is a pained place of desire, of regret and of tracking shots that are as spontaneous and unexpected as a dance number in a musical. It’s a few years after the War, and at the age of 40, Hester Collyer (Rachel Weisz, fiery, tremulous) leaves her life of privilege with her lawyer husband, Sir William Collyer (Simon Russell Beale, warm, concerned, genteelly solicitous) for passion with Freddie, a younger man, a tempestuously alcoholic ex-RAF pilot (callow, bumptious Tom Hiddleston). Bleak wallpaper and crushing emotions follow. Davies is one of the great, lyrical poets of the cinema and one of the great tragedies of film in the past couple of decades is his inability to find finance for his projects. Movies like Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988) and The Long Day Closes (1992) are filled with unforgettable images and passages that go far beyond mere drama, tactile impressions of sensations, of time passing, of time itself stopping, pausing, reflecting. Abiding sorrow is also a constant in Davies’ films, and Hester’s midlife coming to romantic awareness is both melancholy and melodrama. (In the good way.) There are moments in Davies’ work where the images pulse with color, often-rigid yet plainly magnificent compositions, and a rich use of shadow that only the greatest painters achieve on canvas. Davies admires artists like Turner and Jacob van Ruisdael, but Vermeer is his great touchstone, even in the dark reaches of The Deep Blue Sea. In an interview I had with him several years ago, Davies exclaimed, “Natural light falling through a window, there’s something ravishing about it. It’s just ravishing!” And so is his sense of the capacity of the human heart. [Video, Music Box Films.]

4. Detention

“Does this sound fucking PG-13 to you?” Joseph Kahn’s megameta nihilisploitation genre maelstrom, Detention, gets an A+ at the very least for its endearing ADDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD. Suspended from the armature of high school movie memes, horror and otherwise, Kahn and co-writer Mark Palermo flaunt the entrails of movies from Back to the Future to Breakfast Club, from Prom Night to Donnie Darko, nurturing an intense kinship to Heathers, all careening giddily at tender velocity. The veteran video director’s first movie, the motorcycle action yarn Torque (2004), reveled in the possibility of CGI effects now ruined by ubiquity, and attempted a pace since exceeded by Neveldine/Taylor with films like Crank. The kinship to N/T is not kept on the QT here. “We’re beyond midnight movie,” Kahn writes of his welcome follow-up, “We’re a 3am movie.” “Eyes. Glazing,” his heroine, Riley (the starkly physical Shanley Caswell, playing a self-described “loser” who could only become a splendid adult) says. (She’s also handy with early-Winona-styled intonations.) Shameless, relentless and exceptionally pleased with itself, Detention is kind enough to be cruel beyond measure, yet also to be generous with its multimedia mayhem. There’s a raft of video-style gimcracks in the onrushing slipstream, but the snap-crackle-and-skinpop is subcutaneous in its speedy efficacy. The main credits kick things into gear, where names of cast and crew are emblazoned on objects along the length of a heavily peopled high school corridor, including Josh Hutcherson’s name taking the place of “Converse All Star” on the logo of his own sneakers as he skateboards into the picture. And a kiss that ends with a 1990s-obsessed teenager’s “You taste like Luke Perry”? And that same teenager is looked up and down and asked, “Could you look more like Sharon Stone in Total Recall?” (She could not.) A girl obviously in love with her best male friend hellos this way: “Clayton Davis, you are more concept than reality.” “Good taste is not a democracy,” nor are fleeting bad taste references to Heather Mills, Osama Bin Laden and Heath Ledger. Fuck. Everybody” is spoken out loud only a couple of times, but it seems the weary but so-called-life-giving under-the-breath undercurrent of the entire film. One character’s “Gosh fucking darn it” is a fine neologism of a phrase that fits the movie easily as well as “WT-Fucking-F?” Plus, there are at least classy full-screen credits in the end crawl: “YOU HAVE BEEN WATCHING DETENTION” and “MMMBop By Hanson.”

“Does this sound fucking PG-13 to you?” Joseph Kahn’s megameta nihilisploitation genre maelstrom, Detention, gets an A+ at the very least for its endearing ADDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD. Suspended from the armature of high school movie memes, horror and otherwise, Kahn and co-writer Mark Palermo flaunt the entrails of movies from Back to the Future to Breakfast Club, from Prom Night to Donnie Darko, nurturing an intense kinship to Heathers, all careening giddily at tender velocity. The veteran video director’s first movie, the motorcycle action yarn Torque (2004), reveled in the possibility of CGI effects now ruined by ubiquity, and attempted a pace since exceeded by Neveldine/Taylor with films like Crank. The kinship to N/T is not kept on the QT here. “We’re beyond midnight movie,” Kahn writes of his welcome follow-up, “We’re a 3am movie.” “Eyes. Glazing,” his heroine, Riley (the starkly physical Shanley Caswell, playing a self-described “loser” who could only become a splendid adult) says. (She’s also handy with early-Winona-styled intonations.) Shameless, relentless and exceptionally pleased with itself, Detention is kind enough to be cruel beyond measure, yet also to be generous with its multimedia mayhem. There’s a raft of video-style gimcracks in the onrushing slipstream, but the snap-crackle-and-skinpop is subcutaneous in its speedy efficacy. The main credits kick things into gear, where names of cast and crew are emblazoned on objects along the length of a heavily peopled high school corridor, including Josh Hutcherson’s name taking the place of “Converse All Star” on the logo of his own sneakers as he skateboards into the picture. And a kiss that ends with a 1990s-obsessed teenager’s “You taste like Luke Perry”? And that same teenager is looked up and down and asked, “Could you look more like Sharon Stone in Total Recall?” (She could not.) A girl obviously in love with her best male friend hellos this way: “Clayton Davis, you are more concept than reality.” “Good taste is not a democracy,” nor are fleeting bad taste references to Heather Mills, Osama Bin Laden and Heath Ledger. Fuck. Everybody” is spoken out loud only a couple of times, but it seems the weary but so-called-life-giving under-the-breath undercurrent of the entire film. One character’s “Gosh fucking darn it” is a fine neologism of a phrase that fits the movie easily as well as “WT-Fucking-F?” Plus, there are at least classy full-screen credits in the end crawl: “YOU HAVE BEEN WATCHING DETENTION” and “MMMBop By Hanson.”

5. Ajami

Writer-directors Scandar Copti and Yaron Shani’s Arab-Israel Ajami, Israel’s submission for Best Foreign Language Academy Award, is a tense, observant, brutish set of stories unfolding in the rough Ajami ghetto neighborhood of Jaffa, where Jews, Muslims and Christians fail to hold an uneasy truce, even among their own factions and families. Call it “City of Gods.” Copti is Palestinian; Shani is Israeli. A key to the film’s urgent intimacy is that it was shot on location with a largely non-professional cast. A drive-by shooting of a teenager inflames the area. Mistaken identity is key to Ajami‘s narrative tactics, in which bits of story overlap and timelines are fractured, less in the manner of Pulp Fiction than as if the strands of Crash were refracted through one’s own first perceptions of a scene. The key incident working with this strategy peels away slowly, and is infuriating at first, the trick played on the viewer, but on reflection, it’s a powerfully illuminating perception of misperception: in moments of heightened conflict, heart beating, anger rising, what does it take to think clearly, to see all sides, to avoid anger, hatred, the impulse to violence, the firing of a gun? (The obligatory Romeo and Juliet story is key as well.) Boaz Yehonatan Yacov’s cinematography, working with HD in low, grimy light, has a bruising economy and elegance. (On Demand from August 7.)