By Mike Wilmington Wilmington@moviecitynews.com

Wilmington on Movies: The Master

THE MASTER (Four Stars)

U.S.: Paul Thomas Anderson, 2012

No, I won’t call it a masterpiece — though it’s certainly a brilliant and beautiful movie, and better than any other American film I’ve seen this year. So good is Paul Thomas Anderson‘s The Master that it seems to elevate your vision as you watch it, to make something utterly unforgettable out of the American landscapes and people and dramas it shows us. You watch Anderson’s movie, and, unlike most film experiences these days, your eyes and heart and mind open up — or at least mine did. This is what movies uniquely can do — especially a film like this one, shot by Mihai Malaimare, Jr. in gorgeous 65mm, richly imagined and written and directed by Anderson, stunningly designed by Jack Fisk and David Crank, with three great performances at its center from Philip Seymour Hoffman, Joaquin Phoenix and Amy Adams, and excellent performances by the rest of the cast all around them.

The Master is Anderson’s dark tale of a master (Hoffman), a follower (Phoenix), and the master’s wife (Adams): the epic yarn of how a con-job became a big cult, and of how the seemingly placid Eisenhower-era ’50s grew into what would eventually be the volatile Abbie Hoffman ’60s. It‘s the story of an explosive friendship, almost a love affair, between a charlatan and a drunk, a preacher and a hell-raiser, sabotaged by the preacher/charlatan’s determined wife/mother, who wants to break them up. It’s my favorite Anderson film, but, truth to tell, I‘ve liked them all, ever since his arresting debut with the hard-shell/soft-heart poker odyssey Hard Eight in 1997, starring Philip Baker Hall, John C. Reilly, Gwyneth Paltrow and (for the first time) Hoffman.

Here, Anderson gives us anther twisted American saga, in the grand but intimate vein of There Will Be Blood. That 2007 film was a lavishly detailed and deep portrait of America‘s young oil industry inspired by Upton Sinclair’s muckraking novel “Oil!“, with Daniel Day-Lewis casting a scowling spell as a dark-hearted oilman and entrepreneur. The Master is a different kind of American success story. The man on the rise is Lancaster Dodd (Hoffman), a puffy-faced, grinning, peachy pied piper of a guy with a resonant, plummy voice you could pour over crepes, and a Cheshire grin that never fades even when he’s not there anymore. Dodd describes himself as “a writer, a doctor, a nuclear physicist and a theoretical philosopher.” (In other words, a superman who records and interprets the world, heals the sick, builds bombs and then tells us the meaning of it all. ) He has invented an obviously phony pseudo-philosophy, pseudo-psychology, self help scam called The Cause — a burgeoning cult reportedly modeled on science fiction/fantasy writer L. Ron Hubbard’s Scientology, but reminiscent of many a shell game with a charismatic leader, designed to fleece the faithful.

Dodd is the Great False American Papa, worshipped because he’s a bully with a smooth, soft, paternal touch. We first see Dodd hosting a wedding on a yacht in San Francisco Harbor — the yacht is actually the Potomac, which was FDR’s private ship and later belonged to Elvis Presley, then became a drug-smuggling boat and finally a museum — and that’s the place where he meets Freddie Quell (Phoenix).

If Lancaster Dodd is smooth as silk, Freddie is a wild-ass, glinting-eyed mad outlaw of a guy who chews his lip, drinks like a school of fish, looks like a beatnik zombie and behaves like a maniac. We’ve met Freddie before, in the movie’s rapt, violent opening scenes — as a sailor in Guam on a beach at the end of World War II, screwing a sand-woman on the South Pacific beach and masturbating into the surf; seeing nothing but inky cocks and pussies when he’s given a Rorschach test; copulating with a model in the dark room where he works as a department store photographer and chugging home-made liquor laced with (among other bizarre ingredients) paint thinner; mauling and attacking the pudgy male subject he‘s photographing (while the nonpareil Ella Fitzgerald sings “Get Thee Behind Me, Satan“); nearly poisoning one of his fellow California fruit pickers with his mega-hooch, and finally wandering onto Dodd’s (maybe borrowed) yacht, mixing some booze, and stowing away. When he wakes up, he meets Dodd, who has already decided he likes Freddie, because he likes his booze, though the stuff seems to nearly rip out his throat on the way down.

It’s love at first sight, or sfirst sip, or psych test. One of the movie’s great scenes is the shipboard Q & A test, or “process” that Dodd then administers to Freddie, rattling off questions like Jack Webb without brakes, repeating his queries with jackhammer insistence until he gets the answer he wants or senses. It’s a relentless dialogue, played like an interrogation game, batting out evil secrets. It will be echoed later on in an amazingly violent and disturbing jail scene, where Dodd and Freddie are incarcerated in adjoining cells — Dodd for fraud, Freddie for attacking cops — and the two scream at each other while Freddie tears up his cell and destroys his toilet. We know Freddie has contempt for psychological testers (because of the Rorschach test), but he submits to Dodd, just as he will throughout the movie, a Rebel with a Cause, succumbing to a Cause with its Papa.

Dodd is conquered by Freddie as well. We can see the depth of their palship in Freddie’s homecoming to the Dodd’s grandly front-porched home, when the two of them tumble into a bear hug, rolling all over the lawn before Dodd’s stuffer-backed family and his often pregnant wife, Peggy (Adams). Why are they such buddies, such a beaming papa, such a wild and crazy son? Maybe because each gets something important out of the other: Dodd gloms onto the outlaw feelings that he himself tries to suppress or hide, Freddie gets to see and relishes Dodd’s mastery over people and control of a world that has always suspected and rejected Freddie. People something like Dodd’s Peggy, who sees in their relationship a threat to her own ties, and, like many another wife fcd up with her hubby’s bad carousing buddies, does what she can to bring Daddy to his senses. (Is she after Freddie, too? Another of The Master’s mysteries.)

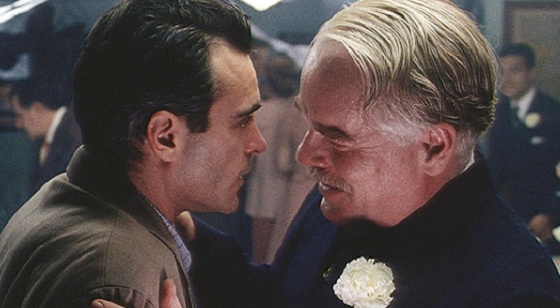

Hoffman and Phoenix are perfect in these roles, and perfectly matched (or mismatched) as well — Hoffman‘s urbane purr setting off Phoenix’s shaggy demonic tantrums and fits. Neither actor has ever been better. Neither has had a more felicitous partner to bounce stuff off. They’re great mad foils: a phony grinning king and his dead-serious glowering clown. And Adams’ Peggy is a great villainness — a gentle-looking conniver who may seem like a pre-feminist strong-woman caught in motherhood, but who is probably just as demonic, in her way, as Paint-Thinner Freddie. Adams herself reportedly compared Peggy to Lady Macbeth, but when she finally unloads on Freddie, she doesn’t have to say “Out damned spot.” He’s a woebegone devil, singed at last.

One important point about Freddie. There’s a scene that Anderson includes — the one near the end where Freddie, after leaving Dodd on his motorcycle, eventually returns to the home of the girl he left behind, Doris (Madison Beaty), and talks movingly to her mother (Lena Endre, of Liv Ullmann and Ingmar Bergman’s Faithless) — which, to me, clearly showed that the sociopath Freddie could have come home and been, to quote the sometime reality behind a cliché, rescued by the love of a good woman, if only he hadn’t gotten sidetracked by The Cause. Maybe I’m wrong, maybe there was no Penelope for this Ulysses and his Odyssey of madness. But it felt real, for a second, despite the joke of having Doris’s married name be Day. Doris Day. “Once I had a secret love, that lived within the heart of me…“ Perhaps it was only another chimera.

Paul Thomas Anderson is a fantastic screenwriter and a great director, and he pushes both skills to the maximum in The Master. It’s a wonderfully shaped and crafted film, shot with a wide-eyed beauty that can sometimes make you feel as happily drunk as Freddie or Dodd. A rebel against the frenetic quick-cut style of most Hollywood movies, Anderson likes to shoot long takes with a moving, roving camera. And The Master is full of virtuoso long-take scenes, like the fight in the department store or Freddie‘s stroll beside the brightly lit Potomac.

But he’s also good at montage (like the “process” scene), and he’s terrific here at evoking the look and feel and sound of the ‘50s, especially by using pre-rock juke box songs: weaving a marvelous quilt of romantic pop that just breathes the ‘50s (from the matchless Ella to Duke Ellington‘s peerless aggregation on “Dancers in Love” or “Lotus Blossom,” to Jo Stafford’s creamily laid-back ballad “No Other Love” and Helen Forrest shining on “Change Partners” — to finally, Hoffman smiling once more at Freddie, his tough guy, and almost whispering Frank Loesser‘s “A Slow Boat to China.“ (My only complaint is that Anderson didn’t include Patti Page’s melancholy ’50s ballad , the “Tennessee Waltz.”)

Then there’s the way this picture is shot. Few movies of 2012 look better — and that’s not just because of Anderson’s eye, and the skills of cinematographer Mihai Malaimare (who also shot Coppola‘s Tetro and Youth Without Youth), but because of the cameras they’re using. 65 and 70 millimeter was the process — now considered almost obsolete and so little used by the industry that Anderson had difficulty rounding up cameras and stock — that David Lean used for Lawrence of Arabia, and that Kubrick used for 2001: a Space Odyssey, and that, more recently Ron Fricke used for Samsara.

All those films looked special, very rich and full, and so does The Master, whether we’re watching the churning waves of the ocean, or the burning rocks in the desert, or the fruit fields or the front porches, or everything else that makes up the movie’s luminous view of America in the ’50s. I watched an hour of The Master, and decided that (along with IMAX), this was really one of the main ways I wanted to look at movies from now on. The Master catches the ’50s as well as most of the great color movies of and about that decade — Vertigo, Some Came Running, Written on the Wind, A Star is Born, and of course, Rebel Without a Cause. It’s an expose’ of the Eisenhower era, but it’s also a 70 mm poem to it.

But not a blind-eyed, suckered poem. Anderson focuses on Dodd the fake and Freddie the madman and Peggy the seeming good woman — and the Cause that for a while, unites them — because he wants to show us something deeply phony and deeply contradictory in American culture: our tendency to lust for and deify father figures, even when they’re picking our pockets. That’s what Dodd does, and that’s why he loves the unabashed outlawry of Freddie. Dodd is the master, but he’d like to be the outlaw too, if only there wasn’t a little woman to keep pulling him back to “sanity.“ The ending of The Master, criticized by some (I’ll just allude to it here, but you can consider it a semi-SPOILER ALERT) is the right, logical climax: the expressions on the faces of the characters, the schisms between them, the song one of them softly sings, and then, the last moments later with two people in bed. It’s all there: Where it all begins, where it ends, where the devil lurks (Get thee behind me), where one man faces his destiny. Hey, don’t we all?

Did I say this movie wasn’t a masterpiece? I must have been kidding.

The worst movie I’ve seen this year! I and some of the audience walked out 1/3 or at the middle of the movie. Although it has over the top performances from Phoenix and Hoffman, it did not elevate the movie as a whole! Too much hype! I have wasted my hard earned dollars and time for this junk of a movie!

Listen to Paul Thomas Anderson’s interview on Fresh Air. All I can say is I don’t like the film was actually intended to be quite what you think it is.

VCQ watched a third of the film and thinks this qualifies him/her to comment on it. Wrong.

Sam E. can’t string a coherent sentence together, but thinks we should take his ideas (?) seriously. Wrong.

^Excuse me is there a point to what you’re writing? Or do you just reflexively need to defend people you don’t know. All I was saying is that Anderson didn’t view the characters exactly the way Wilmington did. If you don’t believe me you can listen to his interview on Fresh Air which I would recommend. http://www.npr.org/templates/rundowns/rundown.php?prgId=13&prgDate=10-02-2012

I loathed it and almost left several times, but stuck around thinking “surely it must get better”, but it never did. It was the worst ‘good movie’ I have ever seen. Complete snorefest.

A friend saw it a couple of days later and agreed completely with me.

Zzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz

Sam, I didn’t “believe” what you said, because I didn’t understand it. It was like reading a Mad Libs passage without the blanks being filled in.

^Okay fine. That said I’m still not sure what purpose your comment had other than to pat yourself on the back for noticing someone wrote a sentence with a word omission. VCQ’s comment may have been moronic but it was at least about the film.