By Mike Wilmington Wilmington@moviecitynews.com

Wilmington on Movies: The Apu Trilogy

THE APU TRILOGY (Four Stars)

Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road)

Aparajito (Unvanquished)

The World of Apu

India: Satyajit Ray, 1955. 1956-57, 1959

1. The Trilogy

Some great movies not only retain all their brilliance as you and they grow older, but actually improve—becoming even better, taking on added luster. One such classic, now nearing the end of its run at the Nuart Theatre in Los Angeles, is the Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray’s masterpiece The Apu Trilogy, a matchlessly moving and beautiful portrayal of an impoverished family’s struggles to survive in the country and city life of early twentieth century India, and of the later life and troubles of their young boy, Apu. Based on a pair of autobiographical novels by famed Bengali writer Bibhutibmushan Bandyopadhyay, the trilogy is one of cinema’s deepest and most poignant renderings of the lives of simple people living hard lives in harsh yet sometimes beautiful surroundings. It is a triumph of domestic drama and of poetic realism—an imperishable treasure.

The Apu Trilogy, both as a single work and in its three separate parts—Pather Panchali (1955), Aparajito (1956-57) and The World of Apu (1959)—is a profound cinematic portrait of the anguish and joys of ordinary lives, so convincing and so heartbreakingly sad, that, as very few movies can, it tends to change your view of the world as you see it. As you follow the film’s central character Apu in his path from childhood (Subir Bannerjee in Pather Panchali) to boyhood (Smaran Ghosal in Aparajito) to manhood (Soumitra Chatterjee in The World of Apu)—and as you watch the everyday routines and travails of his bookish and slightly foolish father Harithar Ray (Kanu Bannerjee), his overworked, dedicated and sometimes overly harsh mother Sarbojaya (Karuna Bannerjee), his playful and adventurous older sister Durga (Uma Das Gupta), his lovely and doomed young bride Aparna (Sharmila Tagore), and, above all, Apu’s elderly, frail, but ebullient old “Auntie” Indir Thakrun (played by that truly sublime actress Chunibala Devi) — these people, and many others in the Trilogy, may become indelible faces in your own personal memory-gallery as well.

The film, as much as any that I’ve seen in decades of watching movies, becomes an overwhelming experience. It stays with you, always: a work of art in the same vein and genre and of the same high quality as John Ford’s Depression America masterpiece The Grapes of Wrath and Vittorio De Sica’s neorealist Italian classic Bicycle Thieves (both among Ray‘s inspirations for his own films). In some ways, it is superior to either of them. Now, playing on a limited run at Los Angeles’ preeminent arthouse, the Landmark Nuart Theater, the complete trilogy seems to me easily one of the supreme film achievements, and one of the great artistic achievements of any kind, made in the twentieth century. If that sounds like excessive praise (and to some people, it will be), all I can say is, put my love of these movies (and especially of Pather Panchali) to the test. See for yourself.

2. The Actress

The Apu Trilogy takes place in the Bengali countryside in the early twentieth century, and (the last two parts) in the cities — and it revolves around a family that, though unrelated to Ray, bears the director’s surname. These fictional Rays live in a small village, in a crumbling ancestral house with a sun-dappled courtyard, where the mother, Sarbojaya (wearing a near constant frown) toils endlessly to keep them fed and clothed and afloat, while the father Harithar (with his frequent silly smiles) writes plays and literary works in a pseudo-classical style while vainly dreaming of dramatic success with local troupes of traveling players. The Rays have two children: the mischievous Durga, who regularly loots a nearby orchard (once owned by her father and perhaps cheated away from him) for fresh fruit — and small, lively Apu, who, like his father, becomes enamored of the theatre and make-believe.

Then there is the Trilogy’s greatest character and performance, and one of the finest performances in the whole history of the cinema: Chunibala Devi as the Rays’ elderly Auntie, Indir Thakrun. Crotchety yet plucky, her face seamed with wrinkles (Chunibala was in her 80s when she made the movie), Indir spends much of her days in the courtyard, reminiscing, clutching her torn, threadbare shawl around her bony shoulders, smiling her radiant gap-toothed smile, trying to be useful, and thankfully gobbling down the fruit Durga steals for her. Occasionally, at night, we hear her reciting, with theatrical gusto, old Indian stories of demons and witches, or singing little songs, mournful yet jaunty (and perhaps the source of the film‘s title, which translates as “Song of the Little Road“), with plaintive verses about poverty and death.

The character of Auntie may sound like fodder for indulgent sentimentality. But one thing we should note about Auntie Indir is that dazzling if nearly toothless smile of hers, shining in the face of most difficulties, and also the ways that, despite her fragile body and advanced age, she regularly tries to help out and be useful: to try to mediate family or neighborhood disputes, to support the children, to sing and entertain. All the while, she also tries to ingratiate herself with her angry cousin Sarbojaya — who seems to dislike and resent the old lady, and to regard her as an albatross inflicted on them all by her husband‘s family.

But for me, Auntie Indir is more than a lonely, well-meaning, sometimes ill-treated old woman. She is, in a way, especially as Chunibala plays her, a symbol of the artist, or of the outsider who longs for a family. (The real-life Chunibala in her 70s and 80s, lived in one of Calcutta’s most notorious red light districts.) In one of her many unforgettable scenes, we hear Auntie performing after nightfall, reciting (with surprising strength and intensity), that little playlet about demons and singing her plaintive song of inevitable poverty and death.

Auntie’s song, for me at least, is a higher work of art than Harithar’s derivative plays, or the bombastic and florid performances of a hack melodrama by the hammy traveling troupe whom young Apu sees. To Sarbojaya, Auntie is simply a troublesome old woman, a drain on their meager finances. To the children, and maybe to us as well, she is a magical creature, a human symbol of the ephemeral beauties of life and love and the need for humanity and kindness set against a brutal world.

She is also a simple old woman, and a brave victim, facing death and the end, with moving equanimity. What finally happens to Auntie, in one of the most devastating scenes in all of the cinema, is so said, and so terrible, and hurts so much to watch, that when I saw the film again on DVD for this review, I had to turn it off and wait a while before playing that sequence and seeing again the last awful confrontation I knew was coming—and what leads up to it, and what follows it.

The episode starts simply: seemingly an unimportant family quarrel that will pass, like many we have already watched in the film. Auntie, who has been complaining about her torn and threadbare shawl for most of the movie, and has been promised a replacement by Harithar (who never brings her one), is given a brand new striped shawl by her other relatives, which she happily wears as she returns home — a gift that unfortunately angers Sarbojaya and leads to an argument in which the younger woman, sick of her own endless toil and perhaps a little jealous of Auntie‘s present, tells the old woman to leave and to stay from now on with her other relatives — something that the fiercely proud Indir has done before. So Auntie gathers up her meager bundle of belongings and goes — her long-sought gift having backfired on her so lamentably.

This time however, she comes back to the Rays’ home later, hobbling on her staff, her bright new shawl draped around her shoulders, looking fatigued and terribly old, and tells her longtime housemate Sarbojaya that she isn’t feeling well and would like to spend her last days in her ancestral home. Sarbojaya, who is sitting and working away alone in the yard — in a cruel gesture that will haunt the rest of the movie and indeed the whole trilogy — refuses and tells her to leave. Spent and quiet, Auntie Indir asks to sit for a while, and then, after only a few moments, asks for some water. Sarbojaya tells her to help herself. And, as she does, Auntie looks at her cousin’s wife, catches her eye and smiles tenderly, hoping perhaps that Sarbojaya will relent and let her stay. When she realizes that won’t happen, her smile—the last of her life—vanishes.

Auntie Indir takes her bowl, sips the water, and then, hunched over and trying to be helpful as always, pours what’s left onto a small plant in the yard. She rises, hobbles away toward the entrance, stops and takes a last look back. Sarbojaya avoids her eyes. Then Auntie departs. The next time we see her close up, she will be seated in the forest, against a tree, eyes closed, dying — while Durga and Apu, at play, discover her and, unaware of her sickness and exile, sneak up to her and try to play with her, reaching toward their beloved Auntie as she topples over.

For some viewers, definitely including me, it will be impossible to watch that devastating final leave-taking, one of the saddest scenes in all of the cinema, and not to weep, and to hope, against all sane and reasonable expectations, that this time, somehow, the film and this scene will end differently, that somehow this time Sarbojaya will relent, and let the old lady come home and rest a while and die in the only home she has known for most of her life, in the courtyard where she always sat, with the family she has tried, in her small yet loving way, to help and to entertain and to be a part of.

That scene, which all by itself makes the movie immortal, does not come from the original novel, where Auntie dies much earlier, in a crowd — but instead was created by Ray for his screenplay, or for the notes and storyboards he used in lieu of a script. Brilliant, unsparing, yet deeply compassionate, it changes the way we look at Apu’s mother, who might otherwise, in the next film, Aparajito, seem an overly sentimental figure, as she sacrifices herself repeatedly for her son Apu. And it demonstrates perfectly Ray’s genius as a film poet, and the humanist power of his storytelling, his brilliance as an artist of life at its hardest, bleakest and most heart-breaking. It shows also the incomparable acting genius of Chunibala Devi — who is so perfect in this role that many people who see the film may mistakenly believe she was not an actress at all, but just some picturesque old lady Ray found in the street, whom he let play herself. She was actually a veteran stage actress with many credits, who had made two other movies, in the ‘30s, and then retired from the screen, only to be coaxed back by Ray.

Chunibala was 80 when Ray began shooting Pather Panchali, on a miniscule budget with a cast composed of mostly amateurs and first-timers. It took Ray three years to make the picture, including one hiatus of more than a year to raise more money when the budget dried up. And the old lady and the other actors stayed with him and his dream project all that time. She died at 83, in 1955, the year the film was released in theatres. (Posthumously, she won a Best Actress award at the Manila Film Festival.)

Chunibala did however see her performance on screen. Ray brought a print of Pather Panchali to her house when it was cut and finished, and projected it for her. He has said that it was a miracle, and one that saved the film, that Devi was able to live all the way to the end of the three year shoot — and to complete her performance so flawlessly, so magnificently. To be a great actor is to be able to transmogrify yourself, on stage or screen, into another creature or human being — and Chunibala‘s performance as Auntie Indir is a work of actor’s art as beautiful and tragic as anything the cinema ever gave us.

3. The Filmmaker

Sadly, The Apu Trilogy is a masterpiece that the mass public in America (and even, to some extent. In India), has mostly ignored, and that many film specialists tend to skip or ignore as well. Everyone who knows movies well knows that they should see it—its reputation is towering—but many avoid it anyway. (To his rare discredit, that brilliant and usually reliable cineaste and cinephile Francois Truffaut is said to have skipped the film at its first Cannes Film Festival showing, reputedely saying that he didn’t want to watch a picture where people ate with their hands.) The Nuart’s run, which is the local premiere of the restored version of all three pictures — painstakingly reassembled decades after the original negative was destroyed by fire — is a film event that should not be missed by anyone who claims to be a cinephile. To love movies, yet to have missed The Apu Trilogy, is akin to saying that you love theater but have never seen a play by Shakespeare, or that you love literature, but have never read a novel by Tolstoy or Dickens, or that you love great music yet have never listened to anything by Bach, Beethoven or Mozart. It is an imperishable treasure — and so is Chunibala Devi as Auntie Indir.

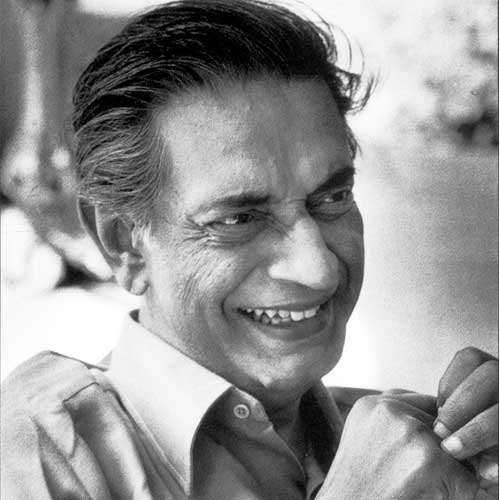

Satyajit Ray, who deserves to be ranked with the greats of his profession — Renoir, Ford, Welles, Kurosawa, Bergman, Ozu, Hitchcock, Fellini, Tarkovsky, Scorsese, Ophuls, Lang, Chaplin, Hawks and other giants of world cinema — was a relatively young man, an artist and a professional book illustrator, when he first read the book “Pather Panchali.” He was assigned to do the illustrations for the Signet edition of the book, and after reading it, he pledged himself (though he had no film experience and was not in the industry), to try to make a movie of the novel. He was encouraged by the great French director Jean Renoir, whom Ray assisted on Renoir‘s now classic Indian-set film The River. And, watching De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves in London, Ray decided it would be possible to make the picture as De Sica made his — with real-life locations and a largely amateur cast. (Chunibala was one of the film’s few professionals). His collaborators included a young first time cinematographer, Subrata Mitra, a young production designer, Bansi Chandragupta (they both later became mainstays of the Indian film industry), and, for the film’s hauntingly beautiful score, the master Indian musician and sitarist Ravi Shankar, who went on to compose, for Ray, the scores of the last two films of The Apu Trilogy as well.

Ray‘s powerful visual gifts as an artist (he wrote and story-boarded the entire film) and his high literary taste and talent illuminate both Pather Panchali and the rest of The Trilogy. The three pictures are masterpieces of black-and-white filmmaking, as well as matchless classics of screen writing, screen acting and screen direction — an astonishing feat for a young man making his first movie. But there were far more than the usual difficulties on the shoot. Ray and his collaborators had to be on call constantly while he kept raising money for the production — with the meager budget constantly drying up. (At one point there was a year-long hiatus in the shooting.) But the film, on its release, became an international critical sensation, and it deserves to be.

At the time, India’s filmmaking industry — dominated by the kind of likably corny and absurd musical/romance/action movies we now call “Bollywood” — was an international critical joke. Ray’s Pather Panchali, which premiered at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (which also provided some of the finishing funds) changed all that. Like Kurosawa‘s Rashomon for Japan, or Zhang Yimou‘s Red Sorghum for China, Pather Panchali put its country and its creator on the world critical map. And Ray –who went on to make more than 30 other features, and many prize-winners (including both of the Apu sequels) — remains, for me, India’s greatest film creator and its most important movie artist. For me also, Chunibala Devi remains India‘s greatest film actress and an eternal treasure of the cinema.

The rest of the Apu Trilogy — the later two films Aparajito and The World of Apu — follow Apu though adolescence and manhood, college, marriage, further tragedy and final redemption, with incidents as real and harrowing, if not quite as moving, as the ones in Pather Panchali. These pictures are full of sadness too, a lot of it revolving around what happens to Sarbojaya, Apu‘s mother. But the ending of the trilogy, the very last shot of Apu and his little boy, is not sad. It is instead, one of the most hopeful and exultant resolutions in all of the classic world cinema.

Apu is ultimately not a false movie hero, or a handsome matinee idol — though Soumitra Chatterjee, who played the adult Apu, became Ray’s regular star and one of the most famous and highly-regarded Indian movie actors. Chatterjee’s work in The Apu Trilogy as an artist and writer from a humble background, shines above everything else he’s done, and that includes a number of other Ray films that have also become inarguable classics — like Devi (which means “Goddess”) and Charulata and Days and Nights in the Forest.

Still, in a way, Ray never surpassed the Trilogy, or Pather Panchali — though to complain about that ranking would be like lamenting the fact that Orson Welles never surpassed Citizen Kane. Ray’s movie, and the complete trilogy, were true labors of love, and they have remained true classics. Satyajit Ray, the young amateur cineaste who worked so hard and so well to achieve his dream, ultimately changed the face of Indian cinema by making the film of Pather Panchali as he wanted to, or as he was able to. To do that, he needed miracles. But life sometime gives us miracles — and life gave one of them to Satyajit Ray. It gave him the old lady in the shawl who smiles and then stops, and sips water from her bowl, and walks away from her home, forever — tired old Auntie Indir, played by the actress named Chunibala Devi.

Seeing the restored APU Trilogy, on 3 subsequent days, at the Nuart, was one of the most sublime film experiences ever, & I have been teaching AFI’s World Cinema class for nearly a decade! Thank you for your equally sublime appreciation– & I’ve been reading everything! Though I cannot wait for the Criterion box-set, I know you will rejoice when you see the restored films projected with a spellbound audience!