By Andrea Gronvall andreagronvall@aol.com

The Gronvall Report: Jay Roach On TRUMBO

Quiz any ardent film fan and you’ll likely find among her or his favorites one or two movies about Hollywood, anything from noir classics like Sunset Boulevard and The Bad and the Beautiful, to the mystery-satire The Player and the exuberant Singin’ in the Rain, to comedies as various as Bowfinger, Matinee, and Who Framed Roger Rabbit. To add to that eclectic mix now comes the biopic-dramedy Trumbo, from indie distributor Bleecker Street. Nimbly directed by Jay Roach, it’s a highly engaging movie about a tough (and touchy) subject, the Hollywood blacklist that began in 1947, and didn’t end until the 1960s.

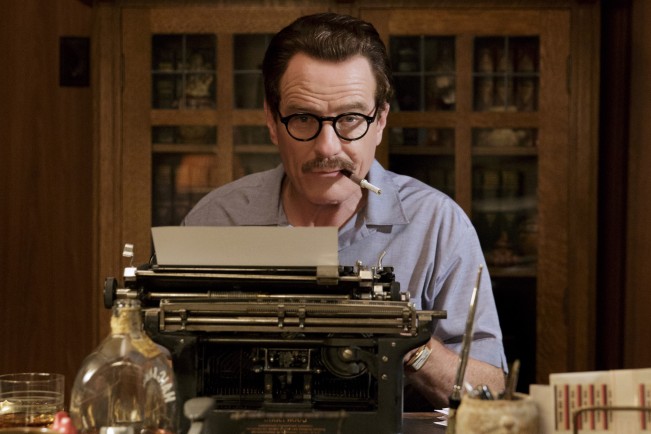

Smoking hot following his Tony Award for “All the Way” and his multiple Emmy-winning run on “Breaking Bad,” Bryan Cranston stars as Dalton Trumbo, the phenomenally prolific author, raconteur and bon vivant who in his postwar heyday was one of the highest paid screenwriters in the nation. As comfortably as he lived, though, he firmly believed that less fortunate working stiffs were entitled to just wages and other protections that labor unions provide, and he was active in leftist politics. How during the Cold War he ran afoul of the House on Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) witch-hunt—he refused to name names of suspected members of the American Communist Party—is only the first part of this fascinating tale. The movie then switches gears to become the story of an intrepid underdog, as Trumbo, banned from working at any major studio, figures out how to fight back, and in the bargain rescues some of his pilloried fellow screenwriters.

Cranston beguiles as the hard-driving, big-hearted Trumbo, who nonetheless was at times irascible and egocentric. As Edward G. Robinson, Michael Stuhlbarg sheds light on the tortured emotions behind a left-leaning sympathizer’s transition into one of HUAC’s friendly witnesses. Helen Mirren plays the venomous right-wing gossip columnist Hedda Hopper with such cool, calculating malice that you wonder why the actress has never been cast as a Bond villain. John Goodman steals scenes as Frank King, the plain-speaking, bat-wielding B-movie producer whose only hard line was his bottom line. But perhaps most persuasive is comedian Louis C.K., showing considerable dramatic skill as Trumbo’s frenemy Arlen Hird (a composite character based on the blacklisted screenwriters Alvah Bessie, Lester Cole, John Howard Lawson, Albert Maltz, and Samuel Ortiz, who with Trumbo and others became known as the Hollywood Ten).

Trumbo screenwriter and producer John McNamara first learned about the blacklist as a student at NYU, where one of his professors was Hollywood Ten survivor Ian McClellan Hunter (played by Alan Tudyk in the film). McNamara has delivered a script that avoids the traps of many a period piece; it bristles with a vitality that makes Trumbo an eye-opening lesson for those too young to have heard of the blacklist, and, for those who know the history, serves as a bracing reminder about our First Amendment rights. As director, there could not have been a more solid choice than Jay Roach. A master of comedy (the Austin Powers trilogy, Meet the Parents, and Meet the Fockers), he showed he’s also sharp about politics when he directed the HBO dramatic movies Recount and Game Change, winning Emmys for each. His latest project for HBO is the film version of “All the Way,” with Cranston reprising his Broadway role as Lyndon Baines Johnson. During his recent swing through Chicago, I found Roach to be open, astute and genial, not to mention funny (but hey, no surprise there).

Andrea Gronvall: With Trumbo you walk a fine line between depicting the tragedies of the blacklist, when careers were ruined.

Jay Roach: And lives.

AG: Yes, most definitely lives. But then the story shifts gears, and in the second part of the film we find ourselves rallying with Trumbo as he matches wits with adversaries and works like a madman to hang on to everything he holds dear. This is a tricky tonal trajectory to pull off. Did you plan it this way in development?

JR: From the beginning I always knew it would be about how Trumbo finds his way. He goes from being at the top, to suddenly being faced with all this persecution and loss, but he says, “I’m going take it on.” And he does.

AG: How do you run your set? You have such a diverse cast, from Cranston, who is so ebullient and versatile, to Stuhlbarg, who is an actor’s actor, to Louis C.K., who most people know only as a comedian. What was your approach with your actors? How many takes do you do?

JR: Those are good questions. Partly because I grew up directing comedy, I do embrace the chaos. We had a very good screenplay, but when you have an actor like Louis C.K., who has tremendous improvisational skills, you don’t say, “Just stick with the script.” Some of my favorite moments with him were his adlibs, where he would inject his character with such attitude, like when Arlen challenges Trumbo with the line, “Do you have to say everything like it’s going to be chiseled into a rock?” And then Stuhlbarg, who has such an impressive resume, does a lot of research into his character. He would come to us with notes as to what he found, along with his thoughts and observations, and we incorporated some of those into the script. But when it came time to shooting, he pretty much stuck with the lines as [finally] written. And Cranston! Every take is great with Cranston. I’d shoot even rehearsals with him, because every single take he did yielded something we knew we could use. Some of the other actors have different styles, of course. I found it useful to let them warm into their roles. I could give them more takes to come up with something, because I knew in the end they would deliver. And then there’s Helen Mirren, who is so smart, so hot, so sexy.

AG: Yes, she is, but she takes umbrage a little at being so often described as “sexy.”

JR: I understand that, certainly. [smiling] Actors are more than just their faces and bodies. Doing multiple takes with her showed how she would arrive at something, in that there were subtle differences with each take. It’s not until you get into the cutting room that you find out how subtle she is. And she’s great at wearing hats, too! First as Elizabeth I, then Elizabeth II, and now as Hedda Hopper!

AG: I assume you are a member of the Directors Guild of America, but are you a member of any other craft guild or union?

JR: Yes, I am a member of the DGA, but I’m not sure how current my membership is in the WGA [Writers Guild of America], which is how I started out.

AG: I ask, not to put you on the spot, but because I found it really interesting that when HUAC was interrogating all those Hollywood producers, directors, actors, and so on, the sessions would begin with the infamous question—

JR: “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?” But when they were interrogating industry members who belonged to a union, they would also ask if those witnesses belonged to a union.

AG: Yes, as if to equate Communism with membership in a union.

JR: Of course, Trumbo was openly a Communist, let’s be clear on that. But many American Communists in Hollywood at that time were not very hardcore [compared to Communists in the U.S.S.R.]. Early on, most were motivated by idealism. They lived through the Great Depression, they saw all this horrible suffering and need, and they wanted to do something about it. Their support of unions [and other causes, like civil rights] was part of their humanist outlook. To understand how deeply Trumbo believed in American laborers’ rights to belong to a union, look at the transcripts of his HUAC testimony, where he stood his ground, maintaining that it was the right of any union member not to have to reveal his membership, in part to protect him [or her] from the inevitable harassment that would follow. What’s very interesting is the fight that was going on in the background between two different writers’ organizations [reporter’s note: described at greater length in Bruce Cook’s biography “Trumbo,” upon which John McNamara based his screenplay]. There was this competition [in the 1930s] between the Screen Playwrights, a group that was endorsed by the studios [as their collective bargaining agent], and the Screen Writers Guild, in which Trumbo would become very active. Eventually, the Screen Writers Guild prevailed. So, when it came time for Dalton and others to appear before HUAC, resentful members of the Screen Playwrights [reporter’s note: who, Cook says, had earlier banded with other industry factions to form the red-baiting Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals] grabbed the chance to brand numerous Screen Writers Guild members as Communist. And because the Communist Party was willing to take on the accused writers’ cause, that further fueled certain perceptions.

Like in that scene with Roy Brewer [played by Dan Bakkedahl], who did head I.A.T.S.E., one of the largest entertainment industry unions, but who also spearheaded a lot of anti-Communist agitation. He goes to threaten Frank King, telling him not to hire blacklisted writers, or else Brewer will bring the press down on him and ruin him. And King takes out his bat and says go ahead, my customers don’t read!

AG: So, were you attracted to this project because of its messages about unions, or about First Amendment rights?

JR: Dalton Trumbo was a guy who was a storyteller committed to language. He came from a kind of old school of writing, one where people who were so verbal, had such big personalities, and so many ideas, translated it all into performance. I was attracted to Trumbo as the story of a man who used the power of storytelling to take on this giant apparatus that was trying to deprive people of their basic human rights. For me, this at its heart is a David and Goliath story.

AG: With laughs!

# # #

How about the truth and some facts:

Fact – Trumbo was a fast writer and during the Blacklist period he was forced to write and rewrite scripts for less money for low-life producers like the King Bros and anyone else who paid him under the table. Trumbo was no hero, he did it for the money. The King Bros’s nephew Robert Rich, who was listed as the author, was an office errand boy and bag man who picked up scripts and delivered cash to pay Trumbo.

Fact – Roman Holiday may be Trumbo’s story, but he was not in Italy during the shooting of the film where most of the script was re-written by Director Billy Wyler and screenwriter Ian Hunter. They wrote script on set day by day and the nights before shooting the film, as was Wyler’s method of film making. Ian Hunter’s son would not return the Oscar when asked by the Academy to do so in order that the Academy issue Trumbo the Oscar decades later.

Fact – Dalton Trumbo lied about being the original author of the 1956 Oscar winning film, “The Brave One”. My father wrote the original screenplay.

Fact – “The Brave One” script marked “#1” with 170 pages is archived in the University of Wisconsin Library where Trumbo donated all his work. The “#1” script’s Title page was removed and no author was mentioned.

Fact – The “first version” (133 pages) and “second version” (119 pages) of the scripts listed “Screenplay by: Arthur J. Henley”.

Fact – The last two scripts listed “Screenplay by Merrill G. White and Harry S Franklin, Based on an Original Story by Robert L. Rich”.

Fact – When the King Bros listed their nephew Robert Rich as author they had no idea that “The Brave One” would be nominated for the Oscar for Best Original Story.

Fact – Robert Rich did not attend the Oscar awards because he was cooperating with the FBI who were watching Trumbo and he didn’t want to be publicly humiliated when the truth came out (FBI File Number: 100-1338754; Serial: 1118; Part: 13 of 15).

Fact – White and Franklin were editors and acting as shills for Trumbo before and after “The Brave One” movie. The King Bros did not initially intend that their nephew Robert Rich be a front for Trumbo. White and/or Franklin were fronts for Trumbo. It was only after the media played up the no-show at the Oscars that the King Bros and Trumbo saw this as a way to sell tickets and Trumbo played the media as well as he wrote.

Fact – My Spanish father, Juan Duval, was a member of the Writer’s Guild of America (West). The WGAW destroyed my father’s original screenplays, which were filed with the WGAW.

Fact – Juan Duval, poet, dancer, choreographer, composer and director of stage and film, wrote the original story/screenplay that The Brave One was based and presented it to a shareholder in the King Bros production company, who then gave it to Morrie King (one of the three King brothers). My father died before film production began.

Trumbo re-wrote the screenplay and removed 50+ pages from the original script, some of which, was about the Catholic ritual of blessing the bulls before a bull fight.

If you read the screenplay marked #1 and the redacted letters in Trumbo’s book, “Additional Dialogue, Letters of Dalton Trumbo, 1942-1962” and compare them to the rewritten scripts and un-redacted letters archived at the University of Wisconsin Library, it’s obvious that Trumbo didn’t write the original screenplay, otherwise, why would he criticize and complain to the King Bros in so many letters about the original screenplay.

My father was born in Barcelona, Spain in 1897, he matriculated from the Monastery at Monserrat and moved to Paris in 1913, where he was renowned as a Classical Spanish and Apache dancer. In 1915, he was conscripted into the French Army and fought in Tunis and then at Verdun, where he was partially gassed and suffered head wounds. He joined the US Army after WWI and was stationed in occupied Germany for 2 years before immigrating to the US where he set-up a Flamenco dance studio in Hollywood, CA. My father worked in film and stage productions, and choreographed at least one sword fighting scene with Rudolf Valentino and made movies in Mexico and Cuba.

In 1935, my father directed the largest grossing Spanish speaking movie up to that time, which starred Movita (Marlon Brandon’s second wife). My father’s best friend was Federico Garcia Lorca and he tried to talk Lorca out of re-entering Spain in July 1936. In 1937, my father published a series of articles about the presence of Nazis in the Canary Islands and in one of the articles, he named who murdered Lorca and why.

My father joined the US Army Air Force in January 1942 and was sent to Tunis where he had fought in WWI. He was fluent in five languages and served as a Tech Sargent. He was Honorably Discharged for ill health in 1943, the same year that Trumbo joined the Communist Party.

Mizi Trumbo refused to talk to me about The Brave One original screenplay.

If Trumbo posthumously received the Oscar for the Roman Holiday story, then my father’s original story which the movie “The Brave One” was based certainly deserves to be recognized by Hollywood and the Academy of Arts and Sciences and posthumously awarded the Oscar for “Best Original Story”.

Before former Director of the Academy of Arts and Sciences Bruce Davis retired, he told me that because of the documentation that I provided him, he was inclined to believe that my father wrote the original screenplay which the movie, “The Brave One” was based.

I request that the Academy recognize my father’s work and issue him an Oscar for his original story and screenplay which the 1956 movie, “The Brave One” was based.