It may seem premature to discuss the 2014 Cannes Film Festival, even before the Oscars 2013 ceremony. But there’s less than 100 days before some of the world’s greatest filmmakers hit the Croisette. So what can we expect?

The Palme d’Or Competition is historically programmed with Cannes veterans. Out of 2013’s slate of 20 Competition films, the Festival only welcomed five new auteurs to the club: Valeria Bruni-Tedeschi, Amat Escalante, Abdellatif Kechiche, Asghar Farhadi and Alex van Warmerdam. That means the remaining 15 films in Competition were by returning Competition directors. That’s a 75% margin, and echoing that number is 2012’s slate, which had 16/22 films by returning filmmakers (or ~73%).

2014 will not be different. Approximately three out of four films competing for the Palme d’Or in May will have been crafted by Competition alumni, and you can mix and match your favorites below.

Armed with an IMDb Pro account, I looked up the 155 Competition filmmakers of the last 11 Festivals (2003-2013). Below are three lists: the raw list of alumni, the list of alumni who have upcoming projects, and the list of alumni likely aiming for a Cannes debut.

Cannes Competition 2014 – The Likely Suspects

Akin, Fatih – The Cut (2014, Tahar Rahim)

Amalric, Mathieu – The Blue Room (2014)

Assayas, Olivier – Clouds of Sils Maria (Kristen Stewart, Juliette Binoche, Chloe Grace Moretz)

Bonello, Bertrand – Saint Laurent (2014, Lea Seydoux)

Cantet, Laurent – Retour à Ithaque (2014, post-prod)

Ceylan, Nuri Bilge – Hibernation (2014)

Cronenberg, David – Maps to the Stars (2014)

Dardenne, Jean-Pierre and Luc – Two Days, One Night (2014, post-prod, Marion Cotillard)

Egoyan, Atom – The Captive (2014, completed, Ryan Reynolds and Rosario Dawson)

Fincher, David – Gone Girl (October 2014)

Hazanavicius, Michel – The Search (2014, post-prod, Annette Bening and Berenice Bejo)

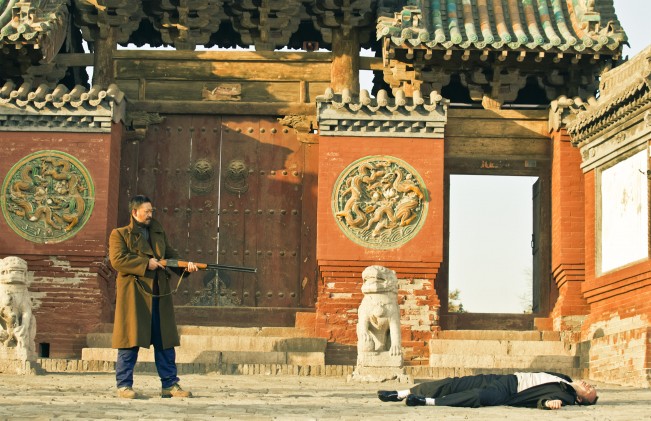

Hsiao-Hsien, Hou – The Assassin (2014, post-prod) (David Bordwell reports at least another year of post is required)

Iñárritu, Alejandro González – Birdman (2014, post-prod, Michael Keaton, Emma Stone)

Jaoui, Agnes – L’art de la fugue (2014, completed)

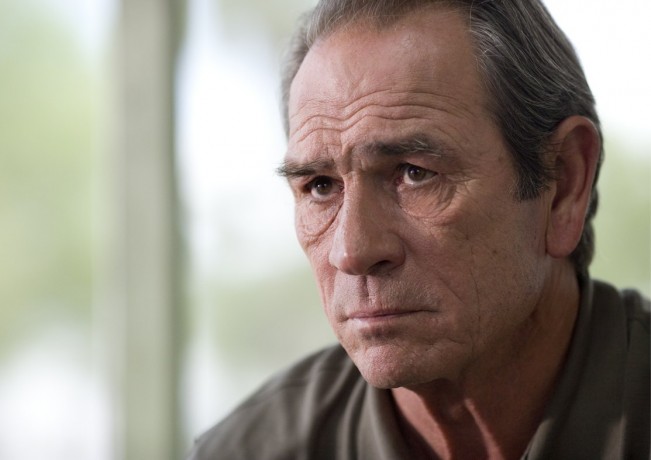

Jones, Tommy Lee – The Homesman (2014, post-prod, Meryl Streep, Tommy Lee Jones, Hilary Swank)

Kawase, Naomi – Still the Water (2014, filming)

Leigh, Mike – Mr. Turner (2014, post-prod)

Loach, Ken – Jimmy’s Hall (2014, post-prod)

Malick, Terrence – Voyage of Time or Knight of Cups (2014, post-prod)

Miike, Takashi – Kuime (2014, completed)

Miller, Frank and Robert Rodriguez – Sin City: A Dame to Kill For (2014, post-prod)

Mundruczó, Kornél – White God (2014, post-prod)

Ozon, François – The New Girlfriend (2014, post-prod)

Téchiné, André – L’homme que l’on aimait trop (2014, post-prod)

Vinterberg, Thomas – Far from the Madding Crowd (2014, post-prod, Juno Temple, Carey Mulligan)

Wenders, Wim – Every Thing Will Be Fine (2014, post-prod, Rachel McAdams, James Franco, Charlotte Gainsbourg)

Zvyagintsev, Andrey – Leviathan (2014, filming)

Some notes:

—Héctor Babenco, Amos Gitai, and Emir Kusturica (all recent Competition alumni) are attached to Words with Gods. This compilation film is an excellent bet for an Out of Competition or Un Certain Regard slot.

—Frank Miller and Robert Rodriguez’s Sin City played in Competition in 2005; it’s reasonable to think the upcoming sequel could as well.

—It isn’t clear if Jane Campion as President of the Jury means a stronger showing of female auteurs in Competition. If I had to guess, though, I would be optimistic about such an outcome.

—Clint Eastwood’s Jersey Boys strikes me as a film that would play Out of Competition, given the material and the tone.

—Guessing how or when Terrence Malick’s anticipated projects will be released feels like an absolute crapshoot, but his Palme d’Or win in 2011 may encourage him to take either Voyage of Time or Knight of Cups to the Croisette this year.

—Vincent Gallo (of The Brown Bunny infamy) has completed his latest film, April, but it remains to be seen if it will emerge from his private vault.

—Angelina Jolie is a red carpet favorite at Cannes, and her film Unbroken (2014) is undoubtedly being courted by the Festival.

—Had I included 2002’s Festival in my research, Paul Thomas Anderson’s Inherent Vice would appear above. The film is indeed expected to debut at Cannes.

—Coincidentally, Gavin O’Connor’s Jane Got a Gun is set to be released on August 29, 2014—exactly two years after the theatrical release of John Hillcoat’s 2012 Competition film, Lawless. Seeing as The Weinstein Company is responsible for both of these Westerns, Jane Got a Gun is almost assuredly going to Cannes—assuming they follow the same release strategy as Lawless.

Competition Veterans (2003-2013) with Listed or Upcoming Projects

Akin, Fatih – The Cut (2014, Tahar Rahim)

Amalric, Mathieu – The Blue Room (2014)

Arcand, Denys – Le Règne de la Beauté (2014)

Asbury, Kelly – Kazorn (2014?)

Assayas, Olivier – Hubris (2014, script), Clouds of Sils Maria (Kristen Stewart, Juliette Binoche, Chloe Grace Moretz)

Avati, Pupi – Un ragazzo d’oro (2014, filming, Sharon Stone)

Bellocchio, Marco – La prigione di Bobbio (2014)

Belvaux, Lucas – Pas son Genre (2014, French release in April)

Babenco, Hector – Words with Gods (2014, segment, post-prod)

Bonello, Bertrand – Saint Laurent (2014, Lea Seydoux)

Cantet, Laurent – Retour à Ithaque (2014, post-prod)

Cedar, Joseph – Jerusalem, I Love You (???)

Ceylan, Nuri Bilge – Hibernation (2014)

Coixet, Isabel – Learning to Drive (Oct 2014)

Coppola, Sofia – Fairyland (2015)

Cronenberg, David – Maps to the Stars (2014)

Dardenne, Jean-Pierre and Luc – Two Days, One Night (2014, post-prod, Marion Cotillard)

Dominik, Andrew – Blonde (2015)

Eastwood, Clint – Jersey Boys (2014, June 20 release)

Egoyan, Atom – The Captive (2014, completed)

Fincher, David – Gone Girl (October 2014)

Gallo, Vincent – April (2014, completed)

Garrone, Matteo – The Tale of Tales (2014, pre-prod)

Gitai, Amos – Words with Gods (2014, segment, post-prod)

Gray, James – The Lost City of Z (2015, pre-prod)

Greenaway, Peter – Eisenstein in Guanajuato (2014, filming)

Haneke, Michael – Flashmob (2015)

Hazanavicius, Michel – The Search (2014, post-prod, Annette Bening and Berenice Bejo)

Hillcoat, John – Triple Nine (2015, pre-prod)

Honore, Christophe – Metamorphoses (2014, post-prod)

Hsiao-Hsien, Hou – The Assassin (2014, post-prod)

Inarritu, Alejandro Gonzalez – Birdman (2014, post-prod, Emma Stone)

Jaoui, Agnes – L’art de la fugue (2014, completed)

Jones, Tommy Lee – The Homesman (2014, post-production, Meryl Streep, Tommy Lee Jones, Hilary Swank)

Kawase, Naomi – Still the Water (2014, filming)

Kaufman, Charlie – Anomalisa (2014, filming)

Kiarostami, Abbas – Horizontal Process (no date, script)

Kelly, Richard – Corpus Christi (no date, script)

Kusturica, Emir – Words with Gods (2014, segment, post-prod), The Bridge on the Drina (2014, status unknown)

Leigh, Mike – Mr. Turner (2014, post-prod)

Liman, Doug – Edge of Tomorrow (2014, post-prod), Reckoning with Torture (2014, post-prod)

Loach, Ken – Jimmy’s Hall (2014, post-prod)

Loznitsa, Sergei – Ponts de Sarajevo (2014, post-prod)

Maiwenn – Rien ne sert de courier (2015, pre-prod)

Malick, Terrence – Voyage of Time, Knight of Cups (2014, post-prod)

Mamoru, Oshii – The Last Druid: Garm Wars (2014, post-prod), The Next Generation: Patlabor (2014, post-prod)

Martel, Lucrecia – Zama (2015, pre-prod)

Meirelles, Fernando – Rio, I Love You (2014, filming)Miike, Takashi – Kuime (2014, completed)

Miller, Frank – Sin City: A Dame to Kill For (2014, post-prod)

Moretti, Nanni – Mia madre (2014, filming)

Mundruczo, Kornel – White God (2014, post-prod)

Nichols, Jeff – Midnight Special (2014, filming, Kirsten Dunst and Michael Shannon)

Ozon, Francois – The New Girlfriend (2014, post-prod)

Rodriguez, Robert – Sin City: A Dame to Kill For (2014, post-prod)

Sang-soo, Im – Rio, I Love You (2014)

Seidl, Ulrich – In the Basement (2014)

Sokourov, Alexander – Francofonia: Le Louvre Under German Occupation (2014, post-prod, Bruno Delbonnel cinematography)

Sorrentino, Paolo – Rio, I Love You (2014), In the Future (2015, pre-prod)

Techine, Andre – L’homme que l’on aimait trop (2014, post-prod)

To, Johnnie – Don’t Go Breaking My Heart 2 (2014, filming)

Van Warmerdam, Alex – Schneider vs. Bax (2015, pre-prod)

Vinterberg, Thomas – Far from the Madding Crowd (2014, post-prod, Juno Temple, Carey

Mulligan)

Weingartner, Hans – Der Taucher (2015, script)

Weerasethakul, Apichatpong – Cemetery of Kings (no date, script)

Wenders, Wim – Every Thing Will Be Fine (2014, post-prod, Rachel McAdams, James Franco, Charlotte Gainsbourg)

Zviaguintsev, Andrei – Leviathan (2014, filming)

Alumni of the Palme d’Or Competition: 2003-2013

Adamson, Andrew – n/a

Akin, Fatih – The Cut (2014, Tahar Rahim)

Almodovar, Pedro – n/a

Amalric, Mathieu – The Blue Room (2014)

Anderson, Wes – n/a

Arcand, Denys – Le Règne de la Beauté (2014)

Arnold, Andrea – n/a

Asbury, Kelly – Kazorn (2014?)

Assayas, Olivier – Hubris (2014, script), Clouds of Sils Maria (Kristen Stewart, Juliette Binoche, Chloe Grace Moretz)

Audiard, Jacques – n/a

Avati, Pupi – Un ragazzo d’oro (2014, filming, Sharon Stone)

Beauvois, Xavier – n/a

Bellocchio, Marco – La prigione di Bobbio (2014)

Belvaux, Lucas – Pas son Genre (2014, French release in April)

Blier, Bertrand – n/a

Babenco, Hector – Words with Gods (2014, segment, post-prod)

Bonello, Bertrand – Saint Laurent (2014, Lea Seydoux)

Bouchareb, Rachid – n/a

Breillat, Catherine – n/a

Caetano, Israel Adrian 2 – n/a

Campion, Jane – Jury President

Cantet, Laurent – Retour à Ithaque (2014, post-prod)

Carax, Leos – n/a

Cavalier, Alain – n/a

Chang-dong, Lee – n/a

Chan-wook, Park – n/a

Cedar, Joseph – Jerusalem, I Love You (???)

Ceylan, Nuri Bilge – Hibernation (2014)

Coen, Joel and Ethan – n/a

Coixet, Isabel – Learning to Drive (Oct 2014)

Coppola, Sofia – Fairyland (2015)

Costa, Pedro – n/a

Cronenberg, David – Maps to the Stars (2014)

Dardenne, Jean-Pierre and Luc – Two Days, One Night (2014, post-prod, Marion Cotillard)

Daniels, Lee – n/a

Del Toro, Guillermo – n/a

Desplechin, Arnaud – n/a

Dominik, Andrew – Blonde (2015)

Dumont, Bruno – n/a

Eastwood, Clint – Jersey Boys (2014, June 20 release)

Escalante, Amat – n/a

Egoyan, Atom – The Captive (2014, completed)

Fincher, David – Gone Girl (October 2014)

Folman, Ari – n/a

Gallo, Vincent – April (2014, completed)

Garcia, Nicole – n/a

Garrel, Philippe – n/a

Garrone, Matteo – The Tale of Tales (2014, pre-prod)

Gatlif, Tony – n/a

Giannoli, Xavier – n/a

Gitai, Amos – Words with Gods

Giordana, Marco Tullio – n/a

Gray, James – The Lost City of Z (2015, pre-prod)

Greenaway, Peter – Eisenstein in Guanajuato (2014, filming)

Haneke, Michael – Flashmob (2015)

Haroun, Mahamat-Saleh – n/a

Hazanavicius, Michel – The Search (2014, post-prod, Annette Bening and Berenice Bejo)

Hillcoat, John – Triple Nine (2015, pre-prod)

Honore, Christophe – Metamorphoses (2014, post-prod)

Hopkins, Stephen – n/a

Hsiao-Hsien, Hou – The Assassin (2014, post-prod)

Inarritu, Alejandro Gonzalez – Birdman (2014, post-prod, Emma Stone)

Jarmusch, Jim – n/a

Jaoui, Agnes – L’art de la fugue (2014, completed)

Jones, Tommy Lee – The Homesman (2014, post-production, Meryl Streep, Tommy Lee Jones, Hilary Swank)

Kawase, Naomi – Still the Water (2014, filming)

Kaufman, Charlie – Anomalisa (2014, filming)

Kaurismaki, Aki – n/a

Kar-wai, Wong – n/a

Khoo, Eric – n/a

Kiarostami, Abbas – Horizontal Process (no date, script)

Ki-Duk, Kim – n/a

Kitano, Takeshi – n/a

Kechiche, Abdellatif – n/a

Kelly, Richard – Corpus Christi (no date, script)

Koreeda, Hirokazu – n/a

Kurosawa, Kiyoshi – n/a

Kusturica, Emir – Words with Gods, The Bridge on the Drina (2014, status unknown)

Larrieu, Arnaud and Jean-Marie – n/a

Lee, Ang – n/a

Leigh, Julia – n/a

Leigh, Mike – Mr. Turner (2014, post-prod)

Liman, Doug – Edge of Tomorrow (2014, post-prod), Reckoning with Torture (2014, post-prod)

Linklater, Richard – n/a

Loach, Ken – Jimmy’s Hall (2014, post-prod)

Loznitsa, Sergei – Ponts de Sarajevo (2014, post-prod)

Luchetti, Daniele – n/a

Maiwenn – Rien ne sert de courier (2015, pre-prod)

Makhmalbaf, Samira – n/a

Malick, Terrence – Voyage of Time, Knight of Cups (2014, post-prod)

Masahiro, Kobayashi – n/a

Mamoru, Oshii – The Last Druid: Garm Wars (2014, post-prod), The Next Generation: Patlabor (2014, post-prod)

Martel, Lucrecia – Zama (2015, pre-prod)

Meirelles, Fernando – Rio, I Love You (2014, filming)

Mendoza, Brillante – n/a

Mihaileanu, Radu – n/a

Miike, Takashi – Kuime (2014, completed)

Mikhalkov, Nikita – n/a

Ming-Liang, Tsai – n/a

Miller, Claude – RIP, 1942-2012

Miller, Frank – Sin City: A Dame to Kill For (2014, post-prod)

Moll, Dominik – n/a

Moore, Michael – n/a

Moretti, Nanni – Mia madre (2014, filming)

Mundruczo, Kornel – White God (2014, post-prod)

Mungiu, Cristian – n/a

Nadjari, Raphael – n/a

Nasrallah, Yousry – n/a

Nichols, Jeff – Midnight Special (2014, filming, Kirsten Dunst and Michael Shannon)

Noe, Gaspar – n/a

Nossiter, Jonathan – n/a

Ozon, Francois – The New Girlfriend (2014, post-prod)

Paronnaud, Vincent – n/a

Polanski, Roman – n/a

Ramsay, Lynne – n/a

Resnais, Alain – n/a

Reygadas, Carlos – n/a

Rodriguez, Robert – Sin City: A Dame to Kill For (2014, post-prod)

Ruiz, Raul – RIP, 1941-2011

Saleem, Hiner – n/a

Salles, Walter – n/a

Sang-soo, Hong – n/a

Sang-soo, Im – Rio, I Love You (2014)

Satrapi, Marjane – n/a

Seidl, Ulrich – In the Basement (2014)

Schleinzer, Markus – n/a

Schnabel, Julian – n/a

Soderbergh, Steven – n/a

Sokourov, Alexander – Francofonia: Le Louvre Under German Occupation (2014, post-prod, Bruno Delbonnel cinematography)

Sorrentino, Paolo – Rio, I Love You (2014), In the Future (2015, pre-prod)

Suleiman, Elia – n/a

Tarantino, Quentin – n/a

Tarr, Bela – n/a

Tavernier, Bertrand – n/a

Techine, Andre – L’homme que l’on aimait trop (2014, post-prod)

Tedeschi, Valeria Bruni – n/a

Thomas, Daniela – n/a

To, Johnnie – Don’t Go Breaking My Heart 2 (2014, filming)

Trapero, Pablo – n/a

Van Sant, Gus – n/a

Van Warmerdam, Alex – Schneider vs. Bax (2015, pre-prod)

Vernon, Conrad – n/a

Vinterberg, Thomas – Far from the Madding Crowd (2014, post-prod, Juno Temple, Carey Mulligan)

von Trier, Lars – n/a

Weingartner, Hans – Der Taucher (2015, script)

Weerasethakul, Apichatpong – Cemetary of Kings (no date, script)

Wenders, Wim – Every Thing Will Be Fine (2014, post-prod, Rachel McAdams, James Franco, Charlotte Gainsbourg)

Winding Refn, Nicolas – n/a

Xiaoshuai, Wang – n/a

Ye, Lou – n/a

Zhangke, Jia – n/a

Zviaguintsev, Andrei – Leviathan (2014, filming)

Background: American; born San Saba, Texas, 1946.

Background: American; born San Saba, Texas, 1946.