Posts Tagged ‘Mildred Pierce’

DP/30 Emmy Watch: Mildred Pierce, actress Evan Rachel Wood

Monday, June 6th, 2011Wilmington on TV: Mildred Pierce

Sunday, April 3rd, 2011U.S.: Todd Haynes, 2011 (HBO)

It’s already started — with the first two of five episodes airing last weekend, the third this Sunday, and two more ahead on subsequent Sundays. But if you’re a hard core movie lover, and you haven’t already sampled the curious and perverse (and sometimes classic) delights of HBO’s current mini-series adapted from James M. Cain’s novel Mildred Pierce, you probably owe it to yourself to start turning it on and gobbling up this archetypal tale of a woman who loves her daughter not wisely but too well.

It worked in 1945 for Joan Crawford and director Michael Curtiz, and it works again now, in different and interesting ways, for Kate Winslet and writer-director Todd Hayes: in this twisty, stylish, psychologically trenchant domestic drama about hard-working, rising restaurateur Mildred, her lazy to-the-manor-born lover Monty Beragon, her conniving and unfailingly horny business partner Wally, her best pal/manager Ida, her estranged ex-husband Bert, and Veda Pierce, the daughter from hell.

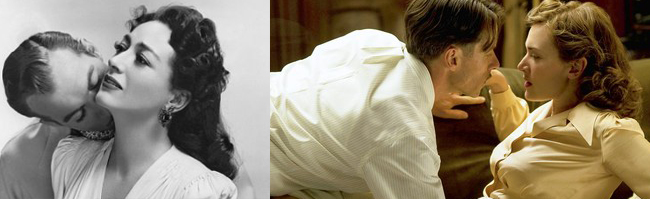

The 1945 Warner Brothers movie — a classic of soap operatic noir — starred Joan Crawford, Zachary Scott, Jack Carson, Eve Arden, Bruce Bennett and Ann Blyth in those roles, and Crawford won the Oscar and jump-started her stalled movie diva career (idling since she‘d left the plush prisons of MGM for hard-boiled Warners) by playing the industrious, devoted, and dumped-on Mildred, still one of the roles for which she’s best known and (after a Hollywood manner) loved.

In the HBO series, the same roles are taken by a deluxe modern cast: Kate Winslet (Mildred), Guy Pearce (Monty), James LeGros (Wally), Mare Winningham (as Ida, a character who was split, in a way, between Winningham”s Ida and Melissa Leo, as Mildred‘s friendly neighbor, Lucy Gessler), Brian F. O’Byrne (Bert) and, as the younger and older Veda, little Morgan Turner and not-so-little Evan Rachel Wood.

It’s a fine cast and a fine production, well and intelligently directed and co-written (with Jon Raymond) by Haynes, a filmmaker who loves period American domestic dramas, and (working with producer Christine Vachon) has lavished enormous care on this one: recreating Cain‘s Depression-era California (Glendale, Laguna Beach and elsewhere), with the care, finicky detail and literary faithfulness one expects to see the BBC lavish on say, a novel by Charles Dickens, George Eliot or Jane Austen. (I love all those writers, and I often enjoy BBC classic novel adaptations. But Haynes could have used more directorial style and flash is time, a little more of Sirk, or of Cukor or Minnelli. Or of Curtiz, whose movies, after all, were loved by R. W. Fassbinder as much as he loved Sirk’s.)

If you‘ve seen the Crawford movie (and if you haven’t, you should now) you’ll know pretty much what’s happened even if you’re coming in after the start — something audiences used to do regularly, in Mildred’s time. Remember that classic mid-movie declaration “This is where we came in?“

This is where I come in too, a week late (after watching the whole series on a DVD screener). I have to confess, though, that I thought Episodes One and Two (both set in 1931, in a story that stretches all the way to 1939) were the most drawn out and disposable of the five, and the movie didn’t begin to move me until somewhere in Episode Two, when Monty Beragon hit his stride. Then, however, this new Mildred Pierce began to really click and spark, thanks largely to the mother-daughter fireworks that were always the tale’s prime weapon, and thanks also to the selfless acting of Winslet.

Warner Brothers may have hot-wired their version, directed by their ace of aces, Michael (Casablanca) Curtiz, with typical ‘40s spice and seasoning: a murder and a mystery and a noirish flashback structure — all elements that we almost expect from any Mildred Pierce by now. But HBO’s version ditches the juicy killing and the relentless cops (oddly, two things we would almost expect from a James M. Cain story) and goes back to the source, back to Cain straight up: his characters, his Mildred, his world, his unvarnished plot, and a lot of his language. And you may be surprised at what a homebody this quintessential American tough-guy writer can be.

Haynes ditches the Crawford movie‘s unforgettable opening, picking up Mildred, where the Warner Brothers flashback (and Cain’s original novel) begin, right after the beach house murder and frame-up and cop intervention that were all tacked on for the 1945 movie. Instead we get suburban angst in sunlight in 1931: with Mildred’s realtor hubby Bert walking out on the family, leaving Mildred with two young daughters, 11-year-old Veda and 7-year-old Ray (Quinn McColgan), to care and earn for in Glendale.

In the mini-series, it’s the height of the Depression, and Mildred, with a little help from Wally (and an affair with the jerk on the side), rises from waitressing (a “shameful” profession that she hides from Veda, who is surprisingly snobbish even at 11) to running her own restaurant — which, thanks partly to Mildred’s virtuosity with pies, is a smashing success. Mildred’s place begins to bring Mildred and her daughters a taste of the good life — which, as always in Cain, is not so damned good.

Another taste, and one that proves intoxicating to both Mildred, and, eventually, Veda comes from the newly successful businesswoman’s hookup with the upper-class bed-bait who becomes Mildred‘s lover, fallen playboy Monty Beragon. Monty, who has somehow lost or eluded much of the family fortune, and still eschews the work he feels is beneath him, is in the process of selling off family property to survive. And Mildred meets him, and falls fast and hard, when she buys a Beragon house to covert into her first restaurant.

Sexual sparks crackle almost instantaneously, and Cain (and Haynes) use Monty and his fellow lazy-arrogant members of the social elite to show how solid and hard-working Mildred is by comparison, and what a little bitch Veda is to be impressed by him, and not by her.

The story, in all three versions, rips apart the class-conscious conservatism that could afflict the U.S, even in the heyday of FDR, and that afflicts us still, especially in politics. To Mildred, Monty represents both a way out of hardship, and an entrance into lust (a Cain specialty, especially when it’s mixed with money). To Veda, for whom Mildred slaves and scrimps to get piano lessons, Monty represents culture and the good life and (later) romance (and eventually, more) — a guide out of Mildred’s world of “kitchens and grease,” which Veda holds in contempt.

A heart-shattering clash was inevitable in the Crawford movie (where one scene with a famous slap, still can make you flinch), and it’s inevitable here too, in a story that very carefully shows how the ruling passions of money and sex can twist psyches, damage lives and rend families apart.

It’s a good story, and the mini-series is a good, solid show, that brings the social dramas of the Depression — as experienced even among people supposedly above it — back to stinging life. One great attribute of Haynes‘ and Winslet’s Mildred Pierce is that, in getting back to the pure Cain, it shows what a truly perceptive novelist and honest painter of real life he really was.

Who would have thought there would ever be a time when a movie adaptation of a James M. Cain novel would look classy, respectable, even socially admirable? (Some knew it already overseas. Cain‘s French admirers, in the land of Emile Zola, included WWII-era existentialist master Albert Camus.) Cain, who brought sex, adultery and murder defiantly into the harsh light of day in literary and movie classics like Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity and Tay Garnett’s The Postman Always Rings Twice, was regarded as so sexy-dirty in the ‘30s and ‘40s that the censorious Breen Office all but blanched at the mention of his books.

And Hollywood‘s top ‘40s screnwriter team, Charles Brackett and Billy Wilder, temporarily split up, when the patrician and conservative Brackett decided he couldn’t sully his hands with the filth of Wilder‘s pet project Double Indemnity. (Brackett’s substitute co-writer for Double Identity: was a good one, Raymond Chandler, but unfortunately Chandler hated Wilder and they never re-teamed.)

Yet the new HBO version of Mildred Pierce is indeed classy, intelligent, ambitious, superlatively mounted, reverent ( as they say) to a fault, and most of all, well and sensitively acted — especially by Kate Winslet as the hard-headed, soft-hearted Mildred, by Wood as the poisonously ambitious daughter Veda and by Pearce as the once-rich playboy/kept man/freeloader Monty.

Ambitious. Sensitive. Well-made. And a bit dull — something you could never say of the Curtiz version (or, in fact, of most other Curtiz or Crawford pictures). Not too dull to bear, of course, and definitely not too dull to admire. One has to applaud the care and devotion which the moviemakers have lavished on the book: their meticulous attention to many details of life in the ‘30s, and the psychological savvy and empathy invested in each performance.

Still, the movie — so carefully produced and directed and artfully acted — does suggest a well-made BBC film of, say, Daniel Deronda or Martin Chuzzlewit, rather than the sordid literary slices of California and the Los Angeles we think of as Cainland. And Chandlerland. And even Crawfordland.

The Haynes version, certainly better than most of the drama on TV, lets us understand and accept the story’s tawdry and evil emotions so well, that it’s sometimes hard to enjoy them or be shocked by them, as Cain certainly wanted his audience to be. And though both Winslet and Wood appear in the nude (full frontal even) it’s so respectfully, if not quite respectably, done, that only a hypocritical prude like the show’s deliciously arrogant Mrs. Forrester (Hope Davis) could object.

Kate Winslet’s performance is obviously one of the great attractions of the whole project, and she gives Mildred a sensitivity, solidity, humanity and depth Crawford probably couldn’t have matched. It’s a really fine, dedicated job. But she doesn‘t have what Crawford gives us, and what makes the 1945 Mildred immortal: that hard-edged glamour, that hint of inner ruthlessness and that determination to take and hold the screen so fierce that it gives you a chill, and makes it almost subliminally understandable how Ann Blyth’s Veda could grow up into one of the great monster daughters of the movies.

Evan Rachel Wood as the older Veda paints a disturbing and all too plausible portrait of the selfishness and heartless social climbing that are sometimes the bad flip side of the American dream. (Wood is really excellent at arousing our dislike.) And the movie’s all-around best performance, with Winslet’s, is undoubtedly Pearce’s as Monty (though we shouldn’t forget how good Zachary Scott was in 1945). Pearce really conveys a sense of charm and rot and quietly vicious entitlement that becomes the mainspring of the movie‘s sense of evil.

The ‘45 movie, which was from Warner Brothers after all, didn’t shy away from the dark, sleazy sordid side of Cain. It made “Mildred“ even more sordid by adding that murder and that mystery, which Haynes — faithful to another fault– has tastefully excised. I’d defend that choice absolutely. Once Haynes decided to go back to the book, he was right to cut it. Totally right. But…

I can’t help it. I missed that shocker of a noir opening, with Scott the silken Southern rat, falling, shot, into the dark, tilted frame — and that later wonderful scene where Crawford’s Mildred lures Jack Carson, perfect as the magnificently slimy Wally Fay, back to the beach house and then frames him for the murder.

In the movie, Wally is given back his original name, Burgan, and he’s played by one time indie movie mainstay James LeGros (Drugstore Cowboy). And he’s dull too — even though LeGros gets to have an actual affair with Winslet, and Carson had to work in the Production Code straitjacket. How can you be dull playing a classic boor and lech? (Maybe it was a political decision, forced on LeGros.) It’s a riddle, but Carson‘s Wally still remains a Hollywood Golden Age classic, while LeGros, an eccentric, inventive character actor who should have a field day, tends to fade from your mind whenever he’s off-screen. (Carson’s Wally, unappreciated by some critics of this miniseries, is also one of the two great Jack Carson performances. The other, of course, is his peerlessly cynical and mean press agent Libby in the Judy Garland-James Mason-George Cukor-Moss Hart A Star is Born.)

SPOILER ALERT

There’s no flashback structure and no sense of noir in the remake, or re-do, because there’s no murder. And despite myself, I felt cheated — partly because the frame-up is such a beautiful, essentially noir scene, and partly because what happens in the book and mini-series that wasn’t in the 1945 movie, and that the murder essentially replaced, seems a little ridiculous here: Veda‘s sudden spectacular radio opera-singing career, which happens when it’s discovered, after years of mediocre piano studies and performances, that she has a sublime coloratura soprano voice.

Wow! This is a jaw-dropper, even though it comes straight from Cain (and reflects his family’s, and his, opera background). That amazingly sudden operatic superstardom really seems, on the whole, far less believable than good old, simple jealousy and murder.

END OF SPOILER

This is where we came in. And I don’t mean to sound ungrateful. I’m not. Haynes and Winslet’s Mildred Pierce is definitely a quality film, and we need more projects like it, need more quality and more intelligence, dammit. There’s no point in complaining that it isn’t great fancy trash as well. What, in the ‘30s and ‘40s (and ‘50s} often seemed like filth and immorality (to more people than just Charley Brackett) now looks more like the honest reporting and the naked truth, something Cain did as well as Chandler or Dashiell Hammett or Horace McCoy. And sometimes better.

As for the HBO Mildred Pierce — a fine adaptation of a major novel by great American writer, with superb acting from Winslet, Wood, Pearce and the others — well, it suffers perhaps only in comparison to the 1945 Warner Brothers movie, to what Michael Curtiz gave us that Todd Haynes doesn’t: that great film noir feel, that wonderful artifice and mesmerizing theatricality of the movies. And Joan Crawford in her finest hour, and Jack Carson in one of his, and Ann Blyth in hers.

Review: Mildred Pierce

Saturday, April 2nd, 2011Kate Winslet is terrific in many ways in Todd Haynes’s lengthy five-episode HBO miniseries adaptation of Mildred Pierce — not the least of which is bringing her own unique sensibility to the role made melodramatically iconic by Joan Crawford back in 1945. Although Crawford won her only Oscar for the role, I’ve never been a huge fan of the Michael Curtiz-directed adaptation of James M. Cain’s 1941 novel of the same name, probably in part because Crawford has just never been one of my favorite old-school actresses.

But no worries, because Haynes has gone back to the source material rather than the Curtiz film, and the end result is far more Douglas Sirk revisisted than Curtiz. Which isn’t altogether a bad thing — Sirk’s Imitation of Life is one of my favorite old guilty pleasure melodramas … and what better time than now to to revisit a Depression-era melodrama revolving around a fulcrum of economics and class and survival?

(more…)