Posts Tagged ‘The Tree of Life’

Alexandre Desplat On Composing Up A Tree

Saturday, May 28th, 2011Howell’s “10 Biggest Mysteries” Of Tree Of Life

Saturday, May 28th, 2011Terrence Malick Acts

Friday, May 27th, 2011More Pitt On Malick

Thursday, May 26th, 2011“Instead of doing little rewrites of scenes to be shot on a certain day, Terry would get up in the morning, and meditate, and write his thoughts about the day’s work. And we got handed these four pages, single-spaced, and they’d be these stream-of-consciousness ideas that we would incorporate into the day’s work.”

More Pitt On Malick

Critics Roundup — May 27

Thursday, May 26th, 2011Kung Fu Panda 2||||Yellow|Red

The Hangover Part II|Yellow|Yellow|Red||Red

The Tree of Life (Limited)|Green|Green|Green|Green|Green

United Red Army (NY)|||Green||

Jack Fisk Footnotes A Slideshow Of The Furnishings Of The Tree Of Life

Thursday, May 26th, 2011DP/30: The Tree of Life, actor Jessica Chastain

Thursday, May 26th, 2011Armani Dressed Sean Penn’s Grown-Up Jack In Tree Of Life

Wednesday, May 25th, 2011A Little Bit More About Malick’s Unfinished Voyage Of Time IMAX Doc

Wednesday, May 25th, 2011Review: The Tree Of Life

Wednesday, May 25th, 2011The tragedies of our lives get buried. Almost immediately after something terrible happens, the burying begins. It’s only natural. If we look too closely at any loss, we tend to find ourselves contemplating the fragility of our existence a little more than we can bear. Like a rush of vertigo, tragedy fills us with the realization that everything we know could disappear at any second. The modern world may be built on the mundane reassurances of day to day novelties – News! Weather! Sports! — but in the big scheme of things, our continued existence (let alone our continued happiness) is anything but certain.

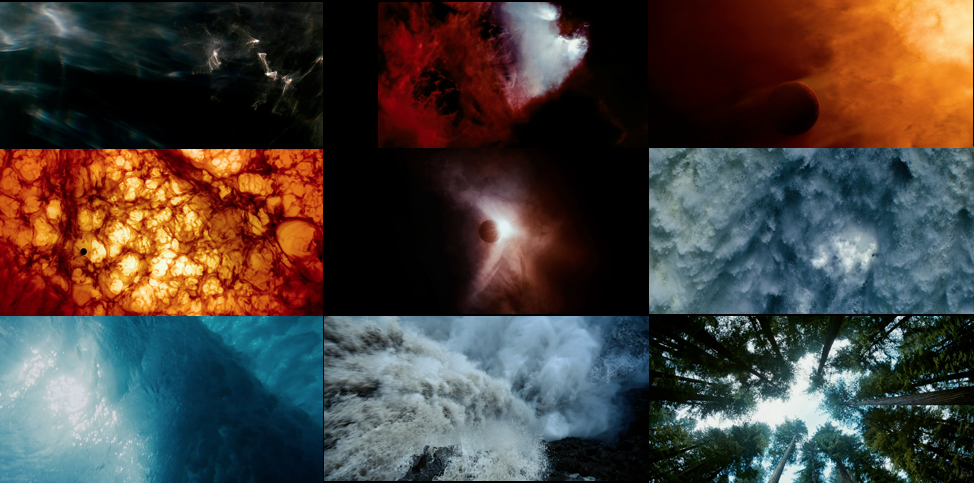

Terrence Malick‘s The Tree of Life rips open the seams of beauty and dread that lie behind one loss. Malick takes a small story about a family and transforms it into an existential voyage, through loosely connected images and music and dream-like moments that are designed to conjure a kaleidoscope of emotional responses. If that sounds hopelessly ambitious, well, Tree of Life is about as ambitious as it gets, straining as it does to capture the impossible beauty of life on earth.

It’s clearer than ever why Malick chooses images that are so pristine, so idealized. He makes films about how it feels to be alive – not what it’s actually like or how it actually looks, but how it feels, and how those feelings sparkle and shine in the haunting space of memory. When the sun sets behind the wheat in Days of Heaven or clouds and sunshine move across the grass in The Thin Red Line” we are made desperately aware of our own survival instinct. In The Tree of Life, Malick offers the impressionistic, evocative details that you find in the best novels, only he delivers them through sounds and images that are already wired into our brains so deeply that they incite a flood of emotional responses: the branches and leaves of a huge oak tree, whipping around in strong wind, boys laughing and running barefoot through empty neighborhood streets, the sound of waves crashing on the shore, a baby’s face in extreme close-up, then his hands, stretching to reach his big brother’s flinching face.

The film begins with a boy named Jack, growing up in a small town in Texas with his family. We flash forward and back in the boy’s life, then zoom in (to a specific moment of loss), zoom out (to the universe) and zoom in again (to a baby’s first cries). Riding along with Malick on this poetic rollercoaster feels heady and dangerous from the start. We know it’s going to be a wild trip, but we have no sense of where we’re going or how it will end. To say that Malick thwarts our expectations of the cinematic narrative is a little bit like observing that Michael Jordan is good at jumping. The central arc of The Tree of Life follows a process of reckoning that has few temporal moorings. The pace of the film isn’t just patient — there is no pace, because having some pace would assume a destination. The only thing that’s clear is that any revelation or resolution here will be hazy at best.

This departure from anything resembling a conventional narrative becomes more obvious in the unfolding of a little interval segment that encompasses… well, the dawn of creation, among other things. As tough as it is not to chuckle and smirk at the outsized ambition and head-swimming grandiosity in play here, it’s probably worth a try, because Malick has rendered the mundane so exquisite and surreal that we can’t casually reject it simply because his scope often transcends our ability to make sense of it. We quite naturally want Malick to meet us halfway, to serve up the beautiful shots of stormy skies and wind in the trees, but also to give us some more clues, some more dialogue to hang all of this free floating emotion around. And it’s pretty tough not to balk at some of his more audacious choices – the CGI rendering that might look more at home in a biochemistry textbook, for example.

But these efforts to place one boy’s life story in the context of the history of all time may amount to a rather elaborate attempt to put a tragedy into perspective. A glimpse of the sun shining behind the side of planet earth has a way of making human foibles look small and transient. With a wide enough lens, a whole lifetime can look like a brief favor, granted by the universe, and our stories can seem as simple and as concise as haikus. We light up like fireflies in the night and then go dark. We’re tossed around by the fates, but our biggest catastrophes aren’t even a blip on the cosmic radar.

What Malick does best of all, though, by zooming out to a wider universe, then zooming in to the buzz of a dragonfly lingering by a sad scene at a swimming hole, is mimic our own attempts at putting our stories in perspective. He captures the first decade of Jack’s life in flashes, the way we might remember our own childhoods: quiet images of a baby in his mother’s arms, a toddler walking through the grass on wobbly legs, a boy running behind his brothers through the woods. There are countless breathtaking shots that must’ve taken days or weeks to perfect. My favorite is a shot from the branches of a tree, looking down onto the grass, where the erratic play of two boys running in circles mirrors the motion of two dogs frolicking in the same frame. Malick slowly prepares us to take in just how whimsical and sensual and malleable the lives of children are, how they drink in everything around them without knowing whether it’s milk or poison.

Finally the scene is set for Jack’s father – well-meaning, impatient, controlling, passionate – to step in and incite palpable fear and anguish in his children’s sweet bubble. What’s heartbreaking — and also courageous, and important — about Malick’s story is that Jack’s father (played by Brad Pitt) isn’t a terrible guy. Instead of serving up either Superman Daddy or Mean Daddy (“Which is he?” we wonder in spite of ourselves, conditioned by countless narratives to expect one of the two), we’re presented with a confusing blend of oppressive and warm and flawed. We develop an uneasy feeling about this man that mixes equal parts affection and suspicion, love and fear, longing and dread. The father here, like any adult, has strong opinions and ideals. He’s trying to teach something important. But he’s not in complete control of himself, so he tries to control everyone around him instead. “For the next half hour,” he says to one son at the dinner table, “will you not speak unless you have something important to say?” This is a man who makes mistakes, day after day, and obviously feels terrible about them. “You have control over your own destiny,” he urges his offspring, while he himself is tossed around like a toy boat on the high seas. He’s just like someone we know, just like our own fathers, just like us.

But from young Jack’s narrow perspective, of course, this dad is alternately a beloved role model and a force of pure evil: He comes into a peaceful house and turns it upside down with his barked directives, with his intolerance. Taken alone, this is a different story altogether. When pressed up against the context of the wider natural world, though, we’re forced to encounter these little accidents of fate, these insults, these injuries, all of it, as something tenuous and sublime. With his unnerving juxtapositions, Malick dramatizes the process of reckoning that is a central part of being alive: we are bold and then we compromise, we assert ourselves and then we retreat, we reject all that is not like us, and then we invite it in again. This imperfect state of affairs is encountered early in the film, when a grown Jack tells his father, over the phone from an elevator, “Hey Dad. I’m sorry I said what I said.”

Most films distill life down to a sequence of clever snippets of dialogue, leading inexorably toward one or two brief but ponderous exchanges. Here, we meander through a life conveyed through poetry and collage. The Tree of Life feels like a vivid waking dream, one that only hints at the path the protagonist has taken in contemplating his past. Despite ample talk of God in the film’s voiceovers, Malick’s ultimate vision seems distinctly secular: We have each other, we have this world, for just a tiny slip of time. Above all, Malick’s message is a compassionate one: we come into this world filled with joy and eventually, we become injured or distracted or greedy and we turn our eyes away from the divine grace of everything around us.

But the lowest moments in our lives, the greatest hurts, present us with an opportunity to take in the full scope of what we have without fear, to gaze at the truth of who we are and where we come from and what we’ve lost without averting our gaze. No happiness lies in wealth or power. There are no clear answers from on high. As the father tells his son, “You’re all I have. You’re all I want to have.” We only have today, to breathe in this life, to savor it for exactly what it is, before it’s gone.

Brody On The Tactile, “Democratic” Urges Of The Tree Of Life

Tuesday, May 24th, 2011On Terrence Malick and an Artist’s Right to Privacy

Monday, May 23rd, 2011“Terrence Malick is extremely shy and you must not attempt to make direct contact with him. You must pretend you are eavesdropping on a private conversation.”

My friend Matt Zoller Seitz posted a link this morning on Facebook to this rare transcript of a public Q&A with Terrence Malick from 2007 at the Rome Film Festival, at which he showed clips from a few Italian films and discussed what he liked about them. Although the audience had been warned that Malick would not talk about his own work, he did in fact show clips from Badlands and The New World and briefly discuss them — perhaps one of the only times he’s ever done so.

(more…)

Malick Was At Cannes Premiere, But Would He Pick A Palme In Person?

Saturday, May 21st, 2011Koehler Dislikes Malick’s “Naive Romanticism”

Thursday, May 19th, 2011“The images are discrete unto themselves, picturesque rather than cinematic, producing the sensation of flipping through pages in a coffee-table photography book (or, in the case of Jack’s family, pictures in the album of a family we don’t know).”

Koehler Dislikes Malick’s “Naive Romanticism”

“The space I’d cleared for The Tree Of Life in my list of the five or ten greatest movies ever made remains empty.”

Tuesday, May 17th, 2011Foundas Detail-Spoils In Rapture Over Tree Of Life’s “Ocean Of Time”

Tuesday, May 17th, 2011Dargis On The Ambition, Vision And Preeminent Immanence In Tree Of Life

Monday, May 16th, 2011“God is everywhere and nowhere—in a ray of sun, a blade of grass.”

Dargis On The Ambition, Vision And Preeminent Immanence In Tree Of Life