By Mike Wilmington Wilmington@moviecitynews.com

Wilmington on DVDs. Pick of the Week: Classic and Box Set. The Killing/Killer’s Kiss

U. S.: Stanley Kubrick, 1956 (Criterion Collection)

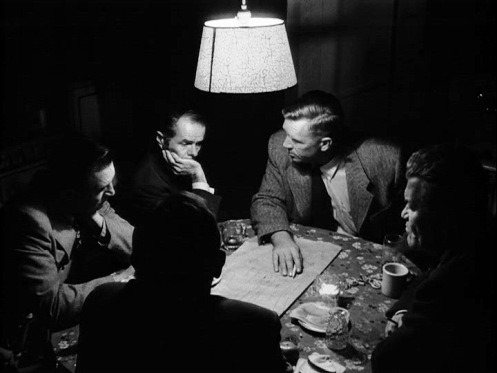

The Narrator (Art Gilmore) in Stanley Kubrick‘s The Killing.

In 1956, at the age of 28, Stanley Kubrick, a New Yorker who grew up in the Bronx and once hustled chess games in Washington Square Park, traveled to Los Angeles and Hollywood to direct the movie that would not only make his reputation and jump-start his international career, but would provide the template — the patented Kubrickian clockwork nightmare with humans caught in the machinery — that would define most of the films he made from then on.

Those later films include acknowledged masterpieces: Paths of Glory (1957), Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), 2001: a Space Odyssey (1968), A Clockwork Orange (1971). But none of them is more brilliantly designed or more perfectly executed than that inexpensive film Kubrick made in L. A. and San Francisco, a little heist thriller called The Killing.

The Killing, looking lustrous here in a new digital restoration, is the kind of movie that used to be called a “sleeper” — the cheaply made, often unusual and brainy surprise hits that aficionados hunted for and buffs loved. Based on a neatly-plotted crime novel, “Clean Break” by Lionel White, it was scripted by Kubrick and nonpareil pulp novelist Jim Thompson (“The Killer Inside Me“), photographed by the great cinematographer Lucien Ballard (The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond), and blessed with an expert, pungent, very iconic cast.

That cast — a sort of lower-case Who’s Who of prime lower-budget noir types — included Sterling Hayden (The Asphalt Jungle), Coleen Gray (Kiss of Death), Elisha Cook, Jr. (The Maltese Falcon), Marie Windsor (The Narrow Margin), Ted De Corsia (The Naked City), Timothy Carey (Crime Wave), James Edwards (The Phenix City Story), Joe Sawyer (Deadline at Dawn), Vince Edwards (Murder by Contract), Jay Adler (Sweet Smell of Success) and Jay C. Flippen (They Live By Night). That’s a formidable gallery, and, with all that talent, assembled and guided by young maestro-on-the-rise Kubrick, the show clicked. It conquered audiences, especially critics.

The Killing was immediately hailed by many as a classic of its kind, the very model of a high-style, low budget, hard-boiled Hollywood crime thriller. “Kubrick is a giant,” Orson Welles said after watching The Killing, and it was the young Welles, of Citizen Kane, to whom the young Kubrick was most often compared. If anything, his third feature’s reputation has grown over the years, as has the stature of the type of movie it embodies: the lean, swift, shadowy, cynical, hard-case ‘40’s-‘50’ crime genre we call film noir.

At 7 p.m. that same day, Johnny Clay, perhaps the most important thread in that unfinished fabric, furthered its design…

Narrator: The Killing

The Killing is a deliberately archetypal movie that takes place in typical noir locations, dark rooms and stark sunny city streets and ill-lit bars — and also, an obvious Kubrick touch, in a chess club. A lot of it, perhaps inspired by Kurosawa’s four-part ‘50s art house classic Rashomon, keeps circling back to that same race at that race track, the fictional Lansdowne (actually the Bay Meadows in Frisco), during the equally fictional $100,000 Lansdowne Stakes for three-year-olds. That mythical race, which opens the picture during the credits, and which we first see uncut in one rapidly panning take around the track, is a prime piece of the “jumbled jigsaw puzzle” (as one character calls it) that will supposedly end as a two million dollar heist of Lansdowne’s Saturday gambling receipts.

Two million dollars, split seven ways. A little like an independent film production? The heist is the brainchild of a brusque self-confident criminal mastermind named Johnny Clay (Hayden), bankrolled by the above-mentioned Marvin Unger (Flippen). And Johnny has devised this complex robbery, which involves many of the people above (with the exception of outsiders Windsor and the two Edwardses, loan shark Adler and Johnny’s gal Gray), and will get its kickoff when crack rifleman Nikki Arcane (Carey), shoots the Lansdowne Stakes favorite, Red Lightning, from a parking lot outside the track, at one of the turns.

In the ensuing melee, Johnny, disguised in a clown mask, with the help of cashier George Peatty (Cook) and bartender Mike O’Reilly (Sawyer), and also a diversion/fight ignited by Johnny’s wrestler/chess player pal Maurice (Kola Kwariani), will hold up the track office, toss a bag filled with the loot out the window to cop Randy Kennan (De Corsia) outside, and make his getaway.

Later, they’ll meet and the loot will be divvied up: straight salary for the shooter and the wrestler, even-steven for everyone else. Generous, maybe too generous for Johnny’s adoring bankroller Marvin, who’s also in love with Johnny — a part and a yen Flippen plays so knowingly and shamelessly, that you feel almost like a voyeur watching him. (Contemporary bluenoses, a little dense, complained that it was misleading and a bad example to show such a warm, caring relationship between two crooks.)

It’s all as cleverly designed and interlocking as a clockwork…heist. And thanks to Johnny, it’s all been planned to the last detail, the last second, the last inch, with each of the seven participants keenly aware of his special part in the robbery, and all of it immaculately orchestrated by Johnny. And he’s a guy who is due. Freshly sprung from a five year stint in the slammer, Johnny is eager to start life anew with his adoring girlfriend Fay (Gray) — just as Hayden’s tough guy Dix in The Asphalt Jungle, wanted, even as he was dying, to get back to Kentucky with Jean Hagen. In Asphalt Jungle, there was a switch: Hayden’s Dix was the muscle, Sam Jaffe’s Doc the mastermind.

But in both roles, Hayden, with his granite-tough face and slightly mad eyes and hurried, racing, whiney delivery, plays that classic Hollywood outlaw character: the integral thief, the generous bad guy. Nobody played it better. And later on, nobody talked of “all our precious bodily fluids” more scarily and hairily than Hayden’s barmy Cold Warrior General Jack D. Ripper in Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove.

Marie Windsor, as Sherry Peatty in The Killing.

SPOILER ALERT

END OF SPOILER

In fact, The Killing is a near-flawless example of the noir form, made with a youthful brio and daring and an insider’s savvy — even though Kubrick was then definitely a Hollywood outsider, a Bronx kid who probably got most of his film schooling from the New York movie houses, TV and maybe the Museum of Modern Art. He learned well though . The movie is laced with top-chop hardcase dialogue, courtesy of supreme tough guy writer Thompson, and with stylish, darkly lit, highly mobile camerawork, courtesy of both Ballard and Kubrick — who was a prodigy Look Magazine photographer in his teens, who loved moving camera master Max Ophuls, and whose cinematography on the even lower-budget 1955 Killer‘s Kiss was superb. The Killing is funny as well as dark, stylish and brainy as well as tough. It’s the kind of sleeper that lays down its hand and rakes in all the chips on its first bet.

Including, definitely, this one: his perfect crime. His perfect score. The consequences…Well, they came later.

Narrator: The Killing

Also includes: Killer’s Kiss (U.S.: Stanley Kubrick, 1956) Two and a Half Stars. Kubrick’s second feature, and his first collaboration with producer James Harris, is one of the most gorgeous-looking low-budget B-crime movies ever — shot by cinematographer Stanley in a style that effortlessly mixes the street-scene poetic realism of movies like Little Fugitive and On the Waterfront, with the film noir expressionism of the whole noir school.

But the script by Kubrick is subpar, mostly in the dialogue. It creaks, while the cinematography soars. A nearly washed up boxer (Jamie Smith) falls in love with the woman across the courtyard (Irene Kane, aka Chris Chase), a dance hall girl who’s tyrannized by her obsessively smitten gangster boss (Frank Silvera). The story sounds trite and that’s how it plays — though Silvera is good, and the classy visuals give Killer’s Kiss a power that keeps you watching, holds you. All Kubrick needed was a writer and a cast, and in The Killing, he got them.

Extras: Interviews with James B. Harris, Sterling Hayden and by Robert Polito (on Jim Thompson); Video appreciation of Killer’s Kiss by Geoffrey O’Brien; Trailers; Booklet with essay by Haden Guest and interview excerpts with Marie Windsor.