By Mike Wilmington Wilmington@moviecitynews.com

Wilmington on DVDs. Co-Pick of the Week: Classic. Tokyo Drifter

The story, from a script by Kouhan Kawauchi, is all about a young gun with ethics and a sense of fair play and an occasional hot temper, named Tetsuya Hondo (played by pop star Tetsuya Watari, a sort of Japanese Elvis or maybe a Japanese Gene Pitney). And it’s about his adoring moll and nightclub chanteuse Chiharu (Cheiko Matsubara) and his cool old ex-gangster mentor Kurata (Ryuji Kita), with whom he’s trying to go legit, even as a yakuza war explodes all around them.

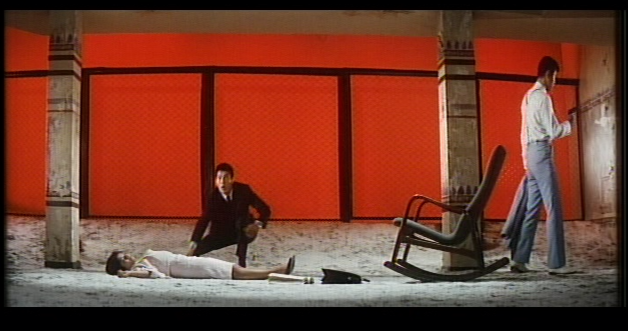

The movie is full of natty yakuzas sneering at each other in expensive suits from whose pockets they pull guns and shoot each other down like dogs. It’s also full of musical numbers sung by Chiharu , who dispenses torch songs at a local night club with shocking red décor, and by Tetsuya himself who keeps singing a maddening title number called “I am a Tokyo Drifter” — lugubrious, mournful, and uptight as Pitney’s “Time — excuse me — Town Without Pity” — and sings it so often that you begin to cringe every time he starts it up again. Chiharu sings torch songs but at least she sings it on stage, Patti Page style, for paying customers and lecherous bosses, while Tetsuya sings, and drifts, all over Tokyo. Only the young Frank Sinatra could have gotten away with something like this, and Tetsuya isn’t even Gene Pitney.

He wasn’t Tony Curtis either. Suzuki later revealed (in an interview on this DVD) that Tetsuya, who was being groomed for movie stardom by the Nikkatsu brass, suffered at first from such paralyzing stage fright that he froze and lost his lines in scene after scene. Suzuki had to get one of his assistants to hide on the set under chairs and behind desks and hit the actor with a broom every time he froze, a shock that usually made Tetsuya remember and spill out his lines. That, in fact, may explain the singer/actor’s performance, in which he often seems to be painfully emerging out of a haze or a temporary coma.

Tokyo Drifter isn’t memorable for the acting or the writing, which don’t make much sense, but for the visuals, which are often astonishing — from the first black and white shots of Testiya attacked by a small mob, to the last scene where (bewilderingly). he rejects his beautiful, talented, faithful girflfriend and walks off into the night, singing “I am a Tokyo Drifter.“ Suzuki, here and elsewhere, does nothing to disguise the idiocy of the script. He simply tries to make it as entertaining and as much fun as he can. And he does.

But even if Seijun Suzuki is no Akira Kurosawa (we sometimes forget that Kurosawa made classic modern noirs and cop thrillers like Stray Dog and High and Low), he doesn’t really need to be. Nikkatsu was a dream factory more in the factory sense. (Directors like Suzuki supplied the dreams, if they were lucky and fast enough.) Nikkatsu movies were written in about a week (by writers who were probably drinking a lot of saki), shot in about three weeks (25 days was the normal Nikkatsu shooting shcedule), edited quickly and dumped into theaters almost immediately, then rotated in and out with the new product.

And Suzuki, who made 42 movies in about eleven years in the beginning, knew how to make them fast and dirty and yet show enough imagination that the aficionados would laugh along with the workers and the kids and people wandering around at night looking for ways to kill time. He made movies with titles like Youth of the Beast and Gate of Flesh and Branded to Kill and Story of a Prostitute, some of them on serious subjects, most of them daring and candid, and he didn’t disappoint his audiences, except on occasion his bosses.

In Tokyo Drifter, the execs were upset about the film’s sometimes whimsical décor, which was oddly chic and colorful in a deranged Looney Tunes/MGM musical sort of way, and about the movie’s coherence, which was tenuous. Finally, when Suzuki brought out the stylish black and white Branded to Kill the next year, they actually fired him for incoherence, and he sued them, and they had him blacklisted for the next ten years, during which he worked on TV — a little like B movies, if you think about it.

Eventually, Suzuki started making movies again and he had the last laugh, He got bigger budgets and he won awards and became a recognized auteur and was totally vindicated.

Suzuki’s filmmaking, so brash, so goofy, so scintillatinglyt nutsy, seems at the other side of the world from Yasujiro Ozu, the supreme Japanese realist who made movies about ordinary Japanese families, with a gentle muted perfectionism. Suzuki‘s pictures, by contrast, seem to be taking place in a bad gangster movie temporarily taken over by artists, or in an opium dream with jazz screaming through the walls. But Suzuki started at the same studio as Ozu, and he worked there as Ozu‘s assistant and knew him well. Decades later, he still spoke admiringly of his old boss and also of both Kurosawa and Kenji Mizoguchi. He just, for his job, had to make different kinds of movies, at least at first.

Just as you’ve never seem poignant family dramas like Ozu’s, or period romantic tragedies like Mizoguchi’s or samurai adventures and war films like Kurosawa’s, you’ve never seen cheap, fast, crazy gangster movies like Suzuki‘s, probably because it’s hard to do something that compelling and ofbeat — especially if you’ve only got 25 days to shoot.

Anyway, if you’ve ever wanted to see a Yakuza movie done partly in the style of Frank Tashlin or Stanley Donen or Chuck Jones, here‘s your chance. Suzuki could turn clichés into art, in Tokyo Drifter and the others, because he was a true original, without alibis. And, by the way, Nikkatsu had a last laugh too: Tetsuya Watari eventually learned how to say lines without a broom and he actually did become a big movie star. But Tetsuya never opened a Vegas act for Sinatra or any of the Rat Pack or even Wayne Newtion, singing “I‘m a Tokyo Drifter” with the orchestra conducted by Nelson Riddle. Let me tell you, I would have paid to see that. Especially if they got Suzuki to shoot the video.

Extras: Interviews with Suzuki and assistant director Masami Kuzuu; Trailer; Booklet with Howard Hampton essay.