By Mike Wilmington Wilmington@moviecitynews.com

Wilmington on DVDs: The Organizer (I Compagni)

PICK OF THE WEEK: CLASSIC

THE ORGANIZER (Four Stars)

Italy: Mario Monicelli, 1963 (Criterion Collection)

on)

I. Marcello

We remember the younger Marcello Mastroianni best perhaps, romancing Sophia Loren or Catherine Deneuve, or living the sweet life in Rome or on a movie location — remember him as the most critically celebrated and internationally popular Italian film matinee idol of the ‘60s, in roles where he wore Armani suits (or suits that looked like Armanis) and sunglasses over which he peered with a bemused grin: roles like the lady killing publicist “Marcello” of Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, or the philandering cineaste Guido of 8 ½.

But one of Mastroianni’s best ‘60s parts, one of the Mastroianni roles and movies that I love best, and one too often sadly unseen or neglected today, was a threadbare, homeless academic, a myopic labor union activist, in the industrial city of Turin in the late 1800s: the impoverished but totally dedicated Professor Sinigaglia.

The Professor (as everyone calls him) is the unforgettable central figure of writer-director Mario Monicelli’s great, neglected comedy-drama on Italy’s 19th century labor struggles, The Organizer (I Compagni). And, unlikely as it first may seem, this seemingly off type part is one of the signature roles and finest performances of Mastroianni’s entire stellar career — a role for which he seems initially all wrong, but proves superlatvely right.

The film, photographed in pungent black and white by Giuseppe Rottuno (who shot Luchino Visconti‘s working class epic Rocco and His Brothers and also Visconti‘s masterpiece on the Sicilian aristocracy, The Leopard), begins with a credit sequence over what seem to be daguerreotypes of 19th century workers and factories, with a rowdy ballad (complete with irreverent lip-farts) on the soundtrack. And Monicelli spends The Organizer’s first half hour or so, without showing us the organizer himself. Instead he shows us gray, dusty Turin and its textile factory, and its workers and some of its manipulative (and deceptively genial) managers, like Maestro di Meo (Francois Perier).

When we meet Mastroianni’s Sinigaglia, we have become fully aware that the Turin workers are being badly mistreated and exploited — and that they’re also a very likable bunch that includes Renato Salvatori (also of Rocco and His Brothers) as Raoul the skeptical womanizer; Bernard Blier (Bertrand Blier’s father and one of France‘s legendary movie character actors) as sad-eyed Martinetti, the workers’ leader; Folco Lulli as Pautasso, a hard-drinking bear; and young worker Omero (Franco Ciolli) and his younger schoolboy brother. We’re also aware that that the managers are seemingly friendly but contemptuous of them — and that the elderly, wheel chair-bound factory owner is particularly disdainful of the “proletariat.”

111

111

II. The Professor

So into this volatile situation pops The Professor, a man on the run who surfaces one night in the basement schoolroom of the local left-wing teacher who is The Professor’s host. The workers have gathered together, more and more discontent with their lot — which includes 14 hour days that begin at the crack of dawn, almost unlivably low wages, and hazardous working conditions that leave one man caught and crippled in the machinery. Sinigaglia listens sympathetically and attentively. Is this his destiny? The Professor is a socialist firebrand, or wants to be one — he has just fled the police in his last city, Milan — but he’s also something of a lovable bumbler. He immediately begins thinking of and organizing a great strike — an action that The Professor doesn’t really know how to strategize, and that the workers aren’t really equipped to win.

An obsessed activist who has abandoned his family and his career to devote himself to the working class. Prof. Sinigaglia is no demagogue or phony, though he is a bit of a Don Quixote — tilting at windmills that are, unfortunately, all-too-real monsters. But The Professor is honestly devoted to Italy’s exploited and downtrodden classes — to the extent that he’s become one of the downtrodden himself, a Chaplinesque gentleman tramp figure whose fingers poke through his gloves, and who is reduced to eating a sandwich his unionists leave behind at a meeting (and shamefacedly, handing it back when the sandwich-owner returns). His clothes and life may be falling apart, but he keeps the struggle alive, with fierce pride and a dreamy eloquence.

Unfortunately, the strike he leads, while at first surprisingly successful and inspiring to some workers and citizens — like Raoul, who takes him in, and a beautiful local hooker, Niobe (Annie Girardot), who gives him a freebie and offers him another bed — is a rickety concoction that may have trouble withstanding the counter-attacks of the owners and managers, their soldiers, their police and their scabs. In fact, as we soon see, thanks to Monicelli’s flair for humanistic dark somedy, Sinigaglia may be leading his friends and disciples to disaster — including the two young brothers, the two observers whom we follow from the movie’s opening, int the drab smokey dawn, under dark skies, of another working day, to The Organizer’s stunning and heart-breaking last shot — an ironic and devastating image that I promise you, you will never forget.

We think of Marcello Mastroianni as an Italian lover and a ladies man, as Casanova — though in fact, Casanova was one of the few Fellini film leading parts in which the direector didn’t cast his favorite leading man. (Fellini chose a ghoulishly made up Donald Sutherland instead). Mastroianni can be more of a nebbish than a Casanova, and when Visconti directed his famous Italian stage version of Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar named Desire, with Mastroianni and Vittorio Gassmann in the leading male roles, it was Gassmann who played Brando‘s role, brutal Stanley Kowalski, and Mastroianni who played Karl Malden‘s part, shy Mitch. Mastroianni is at his best in somewhat dreamy, vulnerable roles — a confused artist like Guido in 8 ½, a weak outsider like the gay man in A Special Day. It’s his extreme good looks that get him his Dolce Vita companions, not any machismo or dash.

As the Professor, Mastroianni alternates between ragged courtliness and the kind of ferocious certainty and torrid political speeches he may have heard at other labor rallies in other cities. He’s more of a clown than a hero, but his very clownishness becomes heroic — and he’s also bizarrely lovable. At the end, after a tragic last confrontation between workers and the establishment, between the poor strikers and the errand boys of the rich, we see The Profesor on his knees, scrambling on the ground in search of his spectacles, without which he can barely see. It‘s a moment that’s sad and funny, in ways that irresistibly recall Chaplin. There’s a dignity and a crazy stature in that scene that makes us love the Professor, and love the actor who plays him — and if he weren’t so sweetly inept and, in the end, easily defeated, we might not love him as much. One of the major themes of The Organizer is a celebration of the ultimate resilience of the workers and their partisans, like the Professor, who lose and lose again — but whom we know, sense will win someday.

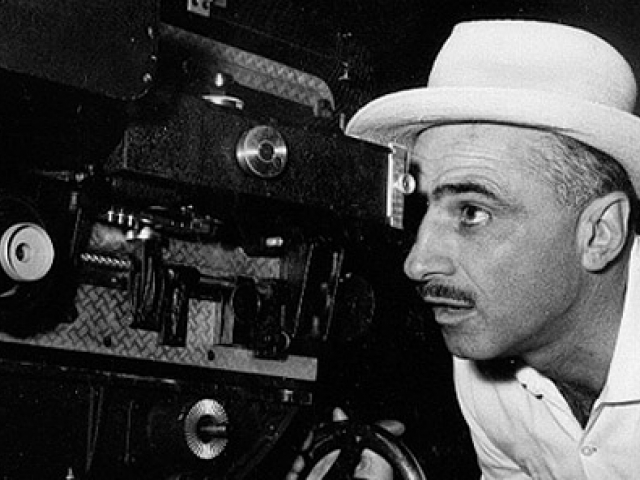

III. Mario

Mario Monicelli, who directed The Organizer and co-wrote it with Italy’s celebrated screenwriting team of Agenore Incrocci and Furio Scarpelli (known as “Age-Scarpelli”) is a great Italian filmmaker who has not received his due in Americs — even though he was one of Italy’s leading film directors and writers from his debut in 1949 (at first co-directing several films with the comedy specialist Steno, and starring the great comedian Toto) to his last film in 2006, The Roses of the Desert, shot when he was 91 — and one of their most popular as well. He is one of my favorites, even though he’s been pretty much ignored in America, and I would happily count him among the all-time Italian film greats on the basis of only two films, The Organizer” and the wonderful 1959 heist comedy Big Deal on Madonna Sstreet, (I Soliti Ignoti) — which costarred Mastroianni, Gassman, Toto and Salvatori and is probably the best film of its kind ever made, along with Alexander Mackendrick‘s The Ladykillers.

But Monicelli’s other pictures, despite his huge Italian and European reputation, have been so ill-distributed in the U. S., and so ignored by critics here, that it’s hard to have seen more than a handful of his movies — even though he made more than sixty, and won many festival prizes (including the Venice Golden Lion for The motly ignored The Great War). The director he seems to me to most closely resemble, especially on the strength of The Organizer and Big Deal on Madonna street, is Billy Wilder — and indeed, Monicelli is known primarily in Italy as one of the masters of Italian comedy. (Hitchcock, after seeing “Big Deal, hired Age-Scarpelli to write for him an American counterpart, which didn’t work out; maybe they needed Monicelli.) The sad-funny thing about The Organizer is that it’s also a comedy — and a comedy that uses Monicelli’s favorite theme of the grand atttempt (like the robbery in Big Deal) that grandly fails. onaizer is a comedy as well — and that’s why, in the end, it so deeply moves us (or me, at any rate). It’s a seirous comedy about a very serious subject, with a tragic ending, but very, very funny at times nonetheless.

The Italian title of The Organizer, I Compagni, means “The Comrades,” and Monicelli was in fact a lifelong socialist deeply committed to the Italian labor union movement, and if that seems strange — given the comical ways he portrays both Professor Sinigaglia and his great strike, we should recognize that it’s Monicelli’s blend of comedy and tragedy, realism and wit that’s responsible for this film’s remarkable depth and the complex emoirions it arouses, the way it generates poignancy and humor and many shadings in between. Monicelli’s I Compagni is set in the late 1800s, after Italy’s Risorgimento, but well before the modern labor movement. So the professor, that sad funny man with the broken glasses, is fighting for something that doesn’t exist yet, and that probably won’t ever exist in the form he imagines it. Like the other great lovers and fools played by Marcello Mastroianni, he lives partly in the skies, partly on earth — partly in the past, partly in the present — partly in heaven, partly in hell. Workers arise, you have nothing to lose but….

Extras: Introduction by Mario Monicelli (2006); trailer; Booklet with excellent essay by J. Hoberman.