By Leonard Klady Klady@moviecitynews.com

Studio Market Share 2014

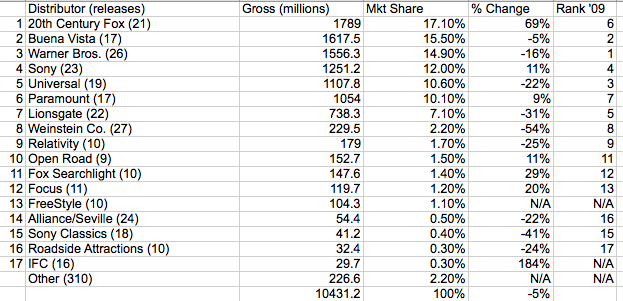

Domestic box office ended the year with a $10.43 billion tally, a 5% downturn from the prior twelve months. Actual admissions will dip for 2014 by roughly 7%.

Bragging rights went to 20th Century Fox, releases from which accounted for $1.79 billion and a market share of 17.1%. It was also a boost for the studio that had finished last among the traditional majors a year ago. With eight of its releases grossing in excess of $100 million, Fox saw its box office expand by 69%.

None of the majors saw a comparable boost or dip, with Universal taking the hardest hit of 22%. But that’s market share, not at all related to profitability. Universal’s lineup was absent a significant sequel or a potential tentpole and a slate of modestly-produced films such as Neighbors and Ride Along crafted a highly profitable year.

Conversely while Sony’s box office experienced an 11% boost its franchise titles fell short of expectations as well as such new releases as the RoboCop sequel and Sex Tape. Matters for that studio were not helped by the hacking of its internal security systems and the curtailed release of The Interview.

2014’s top title was Guardians of the Galaxy, with $332.9 million. The Hunger Games: Mockingjay–Part 1 ranked second with $313.3 million but is poised to beat Guardians‘ total from spillover business in 2015. Seven of the top 10 big grossers were sequels, while one of the originals, The Lego Movie, has already lined up multiple extensions and sequels.

Overall the independents experienced market shrinkage. The anomaly was IFC, whose fortunes turned on a single box office hit, Oscar-touted Boyhood. But the likes of the Weinstein Company and Open Road respectively failed to maximize the perceived potential of such films as The Giver and Nightcrawler.

While the multiple platform release of The Interview was neither well plotted nor organized, it might well hold out the prospect of some intentional simultaneous theatrical/pay-per-view releases of films by the majors. However, for the near future such experiments are likely to be confined to marginal productions … unless some alarming financial situation transpires. The industry historically hates change unless it’s confronted with catastrophe.