By Kim Voynar Voynar@moviecitynews.com

Sundance 2015 Review: The Forbidden Room

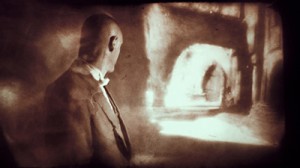

If there’s a director at Sundance who would view assertions that his film garnered the most walkouts of the fest as an indication he succeeded in making the film he intended, it’s Canadian director Guy Maddin, here this year with what I consider his finest and most layered work yet, The Forbidden Room. Known for making trippy, weird stories that are both deeply personal explorations of philosophical ideas, Maddin works in layers of abstract visual poetry. Recline in your seat, breathe in, breathe out, and allow the imagery to flow into you as you try to take it all in; you’re peering directly into Maddin’s brain through the lens of his camera, and given the recurrence of the idea of “brain” throughout his work, that’s about as meta as you can get.

If there’s a director at Sundance who would view assertions that his film garnered the most walkouts of the fest as an indication he succeeded in making the film he intended, it’s Canadian director Guy Maddin, here this year with what I consider his finest and most layered work yet, The Forbidden Room. Known for making trippy, weird stories that are both deeply personal explorations of philosophical ideas, Maddin works in layers of abstract visual poetry. Recline in your seat, breathe in, breathe out, and allow the imagery to flow into you as you try to take it all in; you’re peering directly into Maddin’s brain through the lens of his camera, and given the recurrence of the idea of “brain” throughout his work, that’s about as meta as you can get.

Maddin, working here with his co-director/prodigy/researcher Evan Johnson, weave together interconnected snippets of many different stories, intricately nested within each other like a cinematic matryoshka doll in which each new layer unfolds with its own brilliant palette to assail your senses as their stories dance around and through each other: the crew of a submarine, trapped and running out of oxygen but afraid to disturb their captain, desperately chews flapjacks to release the air bubbles and survive; a lost woodsman mysteriously appears to tell the tale of a fearsome clan. Skeleton women! Kidnapping! Amnesia! Murder!! And of course, Mother … Mother. Always watching!!!

Maddin, working here with his co-director/prodigy/researcher Evan Johnson, weave together interconnected snippets of many different stories, intricately nested within each other like a cinematic matryoshka doll in which each new layer unfolds with its own brilliant palette to assail your senses as their stories dance around and through each other: the crew of a submarine, trapped and running out of oxygen but afraid to disturb their captain, desperately chews flapjacks to release the air bubbles and survive; a lost woodsman mysteriously appears to tell the tale of a fearsome clan. Skeleton women! Kidnapping! Amnesia! Murder!! And of course, Mother … Mother. Always watching!!!

And hey – spoiler!!! – don’t even get me started on the vampire bananas and the hilariously weird wrapper of an old dude in a spectacular bathrobe walking us through the best procedure for taking a bath that’s interspersed throughout. You have to be playing close attention to catch the relevance to everything else going on, but like everything in a Maddin film, there’s a reason its there.

And hey – spoiler!!! – don’t even get me started on the vampire bananas and the hilariously weird wrapper of an old dude in a spectacular bathrobe walking us through the best procedure for taking a bath that’s interspersed throughout. You have to be playing close attention to catch the relevance to everything else going on, but like everything in a Maddin film, there’s a reason its there.

As tends to be the case when absorbing Maddin’s work, it helps to have a sense of humor, some intellectual curiosity and a willingness to be open to cinematic ideas presented in non-traditional ways. This is the lauded directer at his most playful – but also at his most mature in terms of his ability to simultaneously be one of the most collaborative directors working today while maintaining the stylistic aesthetic of a true auteur. If that seems like a contradiction in terms, well, that’s Maddin: inherently original and utterly unique in his thinking about how to convey ideas visually through moving images, yet somehow able to both convey precisely what he wants to others and absorb the input of his actors and crew into his palette as well. The end result, here at least, is a collaborative canvas-in-motion that ultimately reflects Maddin’s true artistic bent perhaps more than any of his previous efforts, precisely because it’s the least insular and introspective of his films to date.

Maddin and Johnson (who also handled the digital manipulation and vividly saturated, shifting color palette) together create a complex, brilliant kaleidoscope of a world where at every turn things shift while still remaining threaded as a whole. Within these connected storyworlds, Maddin’s actors – a spectacularly impressive lineup including Mathieu Almaric, Udo Kier, Geraldine Chaplin and more – bring to life these vivid and melodramatic tales that shun the kind of realism audiences are comfortable with in favor of Maddin’s uniquely metaphorical storytelling.

I wouldn’t call The Forbidden Room necessarily more broadly accessible than his other films, but neither do I have the remotest sense that the director ever even considers such a thing when planning his next cinematic adventure. Maddin works in poetry, not prose, and if his work can be accused of being broadly inaccessible, well, that’s probably exactly the way he likes it. And that’s just fine with me. The Forbidden Room certainly isn’t going to take your hand and gently explain to you what’s going on, but if you set aside expectations of a typical cinematic experience and allow it to be what it is, it’s a simply sublime and deeply satisfying feast for the cinematic soul.

I wouldn’t call The Forbidden Room necessarily more broadly accessible than his other films, but neither do I have the remotest sense that the director ever even considers such a thing when planning his next cinematic adventure. Maddin works in poetry, not prose, and if his work can be accused of being broadly inaccessible, well, that’s probably exactly the way he likes it. And that’s just fine with me. The Forbidden Room certainly isn’t going to take your hand and gently explain to you what’s going on, but if you set aside expectations of a typical cinematic experience and allow it to be what it is, it’s a simply sublime and deeply satisfying feast for the cinematic soul.