By Mike Wilmington Wilmington@moviecitynews.com

Wilmington On Movies: Maggie

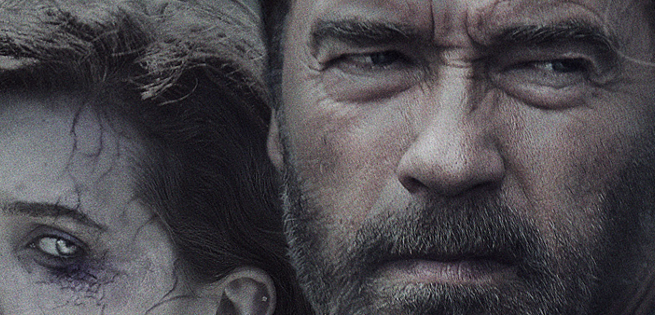

Maggie (Two and a Half Stars)

U.S.: Henry Hobson, 2015

Arnold Schwarzenegger hasn’t made many movies you could describe as art films, and that may be one of the reasons his new picture, Maggie, seems like such an anomaly. It’s at least half of an art film — an attempt at a sensitive genre piece that‘s also a horror show with brains. Written by a one-time NASA engineer named John Scott 3, it’s a dramatic portrait, with realistically drawn characters, of a heartland rural American family disintegrating into fear and grief in the wake of a zombie epidemic that has turned the country into a bleak hell of marauding monsters – one of which is Maggie Vogel (Abigail Breslin of Little Mary Sunshine). Maggie is one of the victims of the plague: a stricken, infected 16 year old, and the daughter of a solid citizen and good-hearted Joe named Mitch Vogel, the role played by Schwarzenegger.

His Mitch is not a bad performance, and it’s the kind of off-type casting that the former megastar should try more often. Schwarzenegger plays Mitch as a gentle farmer and family man with a soft beard — a quiet, anguished, heart-torn, ordinary man so pummeled by the horrors into which has world has descended that he seems drained and wounded, with all the visible tears and hysteria squeezed out of him. There’s none of the cocky ferocity that the old Schwarzenegger displayed in his ‘80s-’90s superstar heyday — though this is a world that could certainly use a Terminator.

His daughter Maggie is in the early stages of a “turn” — a transformation into a full-blown zombie — and its explained to us that it takes several months to complete the metamorphosis after the original infection. In the interim, the zombies-to-be like Maggie are rounded up, held in hospitals and detention camps, and finally executed before they can complete the change.

When we first see Mitch, he’s traveling to a detention center, to rescue Maggie and take her home, an exception for which he at first needs and gets a doctor‘s permission. Schwarzenegger is playing a self-described Everyman here, but there’s a bit of the old ‘80’s Ubermensch too. Mitch refuses to accept the inevitable. He clings to a hope that has no foundation, and that Maggie herself (played with scarred intensity by Breslin) has let slip away from her. For the rest of the movie, we see that inevitable coming closer and closer, with everyone around Mitch — his wife Caroline (Joely Richardson) , his neighbors, local lawmen and authorities — pulling him toward the dreadful decision he refuses to make. Tormented beyond reason, Mitch not only is forced to endure the death of a loved one by fatal disease, but has to personally prepare for her annihilation as well.

There is no humor in the movie Maggie, no lightness of touch or compensating irony. It’s not only a serious film, but a deadly serious film — deadly in several senses, not all of them admirable. Director Henry Hobson, making a creditable feature debut, has named his main cinematic and visual influence in the picture as Terrence Malick (Badlands, Days of Heaven, The Tree of Life), one of the most serious, and poetic, of all American directors, and one of the last models you’d expect to see for a zombie movie. But you can see touches and flashes of Malick often in the scenes of waving grain fields, rustic family farm houses, a horizon that seems to be beckoning you on, and that huge vault-like over-arching sky.

The movie is one of the grayest and most cheerless I’ve seen recently, gray and cheerless and sunless in the way American movies often become when they’re envisioning the apocalypse and what follows it. And Schwarzenegger’s and Breslin‘s performances are gray and post-apocalyptic too. It’s almost as if Mitch were turning as well as Maggie, infected by the sense of blight and death and hopelessness that shrouds almost every scene, nudged along toward the inescapable dread that’s swallowing them all up. Richardson as Mitch’s wife and Maggie‘s stepmother Caroline, seems less infected. She‘s in some ways a typical American mother, typically protective. But she gives up on Maggie far sooner, fleeing to another farm with their other children. Father and daughter meanwhile, enact a kind of horrific love story, in which both of them watch their world die and both of them seem doomed to become (different kinds of) the walking dead.

I admired the film’s ambition more than I liked its result. Maggie comes from a script that’s been on the Hollywood Black List of the best unproduced screenplays around town. But it’s not the masterpiece or quasi-masterpiece that might imply, and the finished movie, unless it was severely altered or cut, doesn‘t seem to warrant that high praise. Certainly everyone involved — including cinematographer Lukas Ettlin and production designer Gabor Norman as well as Hobson and the actors — is giving their best, working hard to generate the horrendous darkness and the shiver of lost grace the movie needs. But their effort is a little too apparent, too obviously metaphoric. If you compare Maggie to most of the crud that comes out these days, including cruddy zombie movies, it seems somewhat better than the norm. But that “somewhat” is crucial. I kept expecting a killer scene between Mitch and Maggie, one that played devastatingly with their past happiness and present grief, and in which he reached out to the daughter of his memories and had to confront the daughter of today and dying flesh, but it never quite came. Or if it did, I didn’t recognize it.

There’s been so many movies in recent years that imagine the end of the world, or almost the end, that it seems we (audience and filmmakers) have become infected too, poisoned with overwhelming despair and pessimism about what lies ahead. It’s as if our popular storytellers, obsessed with superheroes, yearned for a real ubermenschen (the kind Schwarzenegger once played), to stave off the inevitable. Of all these movies, Maggie is one of the most despairing. But that genuine despair it reflects and the sensitivity with which a lot of it is made, doesn’t necessarily alleviate or redeem the dreariness into which it often descends.

The entire genre of zombie movies, which peaked early in 1969 with the first Night of the Living Dead, is like a horror-movie equivalent of the ‘60s Theatre of the Absurd, with Beckett’s tramps waiting for a Godot that might well be the gatekeeper of the end of the world, and Ionesco’s stampeding people turning into rhinoceri that might well be marching zombies. That’s why the attempt at a mixture of horror and realism in Maggie doesn’t quite work, The quasi-realism and cheesy throb of absurdity of George Romero’s part-comic zombie sagas plays better and, I would argue, even affects you more deeply.

I‘m not saying this movie doesn’t work or couldn’t; Scott’s script strikes me as a potentially very good one, that needed more development, more daring. And, in the end, whatever I think, everyone involved here deserves credit for trying something different, for approaching their work with a heartfelt sincerity and high aspiration horror movies usually eschew. But, just as a zombie needs people to munch on, this movie about love and terror needs even more heart to chew on. Its dead need to walk before they can run; its living need to connect with each other and with the dead souls around them. They need more humanity and more awfulness. And that includes Arnold the one-time ubermensch.