By Jake Howell jake.howell@utoronto.ca

Sundance 2014 Review: What We Do In The Shadows

Fans of New Zealand’s premiere comedy export “Flight of the Conchords” have much to look forward to in Jemaine Clement and Taika Waititi’s What We Do in the Shadows, which toured Sundance 2014’s midnight program as the “vampire mockumentary”—a tagline that initially felt more like a warning than an enticement.

Fans of New Zealand’s premiere comedy export “Flight of the Conchords” have much to look forward to in Jemaine Clement and Taika Waititi’s What We Do in the Shadows, which toured Sundance 2014’s midnight program as the “vampire mockumentary”—a tagline that initially felt more like a warning than an enticement.

The film is one of the festival’s most pleasant surprises because it’s gotten to the point where certain horror tropes are dead or dying: recent zombie movies have been more shambling than exciting; vampires in general have become anemic and fangless (shout-out to the Twilight series, driving nails into the rhetorical coffin).

It’s clear that Waititi and Clement (who are triple-threats here, writing, directing, and acting in the film) have similar issues with the vampire mythos going six feet under, inspiring them to create something that situates the folklore revenant into something contemporary and hilarious. They’ve turned the monster on its head, finding levity in darkness.

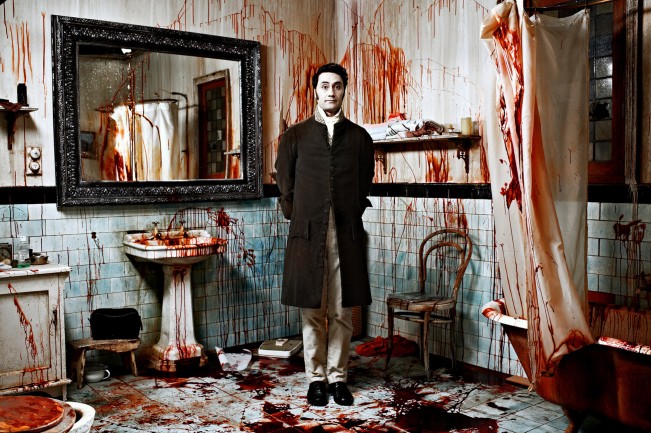

Things are batty at home for vampires Vladislav (Clement), Viago (Waititi), and Deacon (Jonathan Brugh), who are flatmates in a dilapidated Wellington mansion. Opening with a fake intro video crediting the film to the New Zealand Documentary Board, What We Do in the Shadows follows these vampires through their night-to-night lifestyle, including eating humans, going dancing, and antagonizing werewolves (the alpha-male of which played by Rhys Darby, who played band manager Murray on “Conchords”). Joining the trio is Nick (Cori Gonzalez-Macuer), a recently-turned vampire who recklessly enjoys the powers bestowed upon him, and it stretches the patience of his fellow flatmates.

There’s also an arc leading up to an annual event that the various ghouls of Wellington all attend—the “Unholy Masquerade Ball”— but the focus here is in the mundanities of eternal life—ages of which are spent with idiosyncratic roommates (“Do your bloody dishes!”). To that end, Clement’s signature unsmiling cynicism as the swarthy Vlad perfectly offsets Taika Waititi’s optimistic and cheerful Viago. Brugh’s Deacon is a wildcard with a penchant for fashion; his familiar and human servant Jackie (Jackie van Beek) cleverly reveals how juvenile these ancient vampires actually are. Nick’s carelessness is the catalyst for some of the film’s funnier gags, and he brings along his best friend Stu (Stuart Rutherford), a straight-man mortal who the vampires all love the company of. For reasons unknown, Jemaine Clement’s “Conchords” singing partner Bret McKenzie is nowhere to be seen; whether or not he was asked to participate isn’t clear—oh well.

There are lots of jokes to be made about vampires in the digital age, but the film resists making the easy ones. The majority of the comedy relies heavily on wry equivocation humor and vampire-out-of-water ignorance, which you may think carries a certain amount of obviousness. But Clement and Waititi prove this to be a very good idea, and the directors have timed things brilliantly. There are more than a few lines that will make you laugh minutes after they’ve landed because of how stupid (smart) the pun actually is: “I’m going to stay in and do my dark bidding,” Vlad says. “What are you bidding on?” Viago replies. Vlad turns around from his computer and it’s revealed he’s on eBay: “A table.”

There’s also a Spinal Tap-esque knowingness to What We Do in the Shadows, and it’s a welcome comparison. Curiously, there are no songs to nod along to—a fact that is rather unlike Clement’s career—but the film’s mockumentary approach to the premise is a fun one; executed well with personal interviews and run-and-gun shots a la reality television to keep things engaging (alongside some very creative editing, stitching together cuts to fake a single take). In terms of the script, there’s little to criticize other than a bit of sag in the fracas of the “Unholy Masquerade Ball.” This (un)deadpan Kiwi comedy is memorable, entertaining, and very, very funny; a bonafide, blood-red gem of this festival.