By Gary Dretzka Dretzka@moviecitynews.com

Real Life Meets Cinema: Issues Raised by Burma VJ Emphasized by Arrest of Activist

There was a day, not so long ago, when no potential blockbuster could be launched without the benefit of an elaborate publicity stunt. Every new Jaws was preceded by sightings of great white sharks on beaches from Cape Cod to Key West, and on-set romances had a way of dissolving as soon as the red carpets were rolled up.

There was a day, not so long ago, when no potential blockbuster could be launched without the benefit of an elaborate publicity stunt. Every new Jaws was preceded by sightings of great white sharks on beaches from Cape Cod to Key West, and on-set romances had a way of dissolving as soon as the red carpets were rolled up.

Today, Tom Cruise need only bounce on Oprah’s couch to be rewarded with the kind of publicity not even money can buy.

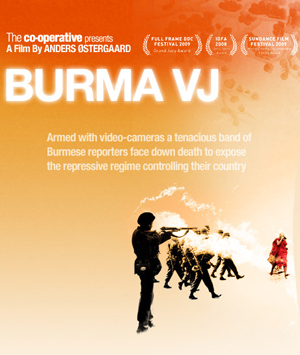

Only Satan’s flack could have brokered the news reports that have preceded the limited release of Burma VJ: Reporting From a Closed Country. As if Anders Østergaard’s documentary on the 2007 Saffron Revolution weren’t compelling enough, Myanmar’s military junta decided this would be the perfect time to re-arrest the country’s foremost pro-democracy opposition leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, and force her to stand trial before a kangaroo court appointed by her enemies.

What, you weren’t aware that the Noble Peace Prize winner – often mentioned in the same breath as Nelson Mandela – has been sitting in the “darkest hell-hole in Burma” for more than a week, already? Oh, that’s right: America has been all a-Twitter with the finales of Dancing With the Stars and American Idol. You’re forgiven.

Just to bring everyone up to date: on May 6, a U.S. citizen, described variously as a “fool,” “this wretched American” and “a self-appointed savior” of the Burmese people, handed the junta the only excuse it needed to revoke Suu Kyi’s house-arrest status and throw her in prison. John Yettaw, a devote Mormon and Vietnam vet, accomplished this by swimming across a lake to reach her home. It was the second time in the last year that he had broken into her heavily guarded Rangoon house.

Along with two other women, Suu Kyi has been charged with breaching the terms of her house arrest, which was set to expire at the end of May. If convicted, she could be forced to remain behind bars – without access to reporters or her supporters — during next-year’s election campaign.

Westerners are cautioned, here, not to read too much into the possibility of democracy being allowed to ride roughshod over one of the most thoroughly corrupted nations on the planet. The last time national elections were held, in 1990, the victory won by Suu Kyi’s political party was nullified by the junta, which has remained in power ever since. The frail 63-year-old woman has spent 13 of the past 19 years in jail or detained in her home, despite the lobbying of most world leaders, including the last three American presidents.

If the outcry has been less than deafening, it’s probably because Burma – the rulers changed the country’s name to Myanmar, and Rangoon to Yangon, in 1989, after protests were brutally suppressed – hasn’t threatened to become a nuclear power, like North Korea and Iran, or become a shelter for terrorists. Trade embargoes have been sanctioned, but, of course, one nation’s police state is another’s business partner.

Considering the iron-clad restrictions imposed on the national and foreign press by the military junta, Burma VJ: Reporting From a Closed Country could hardly be a more remarkable document. Using footage shot and smuggled out of Myanmar, it describes the ill-fated 2007 anti-government protests, which began when the ruling generals decided to remove subsidies that kept fuel affordable, but soon escalated into a broader condemnation of repression and lack of civil liberties.

While the police and soldiers carried guns and billy clubs, video journalists were forced to make do with cell phones, hand-held cameras, the Internet, laptop-computers and satellite transmitters. If it weren’t for the techno-guerrilla Democratic Voice of Burma, few people inside or outside the largest country in Southeast Asia would have learned the true extent of the protests or witnessed the beatings and murders of activists and monks.

Needless to say, the amateur journalists risked much more than the confiscation of their cameras and computers for covering the protests. People were killed, beaten, jailed and made to disappear.

The Danish documentarian, Østergaard, had been asked by one of the film’s producers to make a film about the DVB, whose video communiqués were being edited in Oslo and fed back to Burmese viewers, by satellite. The idea was to put a tight focus on a personable cameraman, “VJ Joshua,” whose reports the director had first considered to be mundane.

As word began to spread about possible strikes and other protests by consumers, he began to see the potential for a much more compelling film. The drama intensified after Joshua was caught filming a police action and arrested. He was released, but followed in the hope he might be stupid enough to lead authorities to his compatriots.

By the time the protests began in earnest, Joshua was in possession of new equipment, a more secure safe house and a front seat to history. The images he captured made the round trip from Rangoon to Norway, and back, then also were picked up by CNN. Joshua also was privy to a plan by the nation’s monks to demand reforms of the generals, and, if that failed, a strike that would preclude the military from religious rites.

Østergaard knew that the participation of the monks, with their saffron robes and shaved heads, would prove irresistible to news directors around the world, and the only images of them would come from DVB. What couldn’t have been predicted with any precision was how the junta would counter the monks, who were revered throughout the country.

Unwilling to risk any threat to their standing, the generals came down as hard on the holy men as they would a common criminal. The monks who participated in the marches of the Saffron Revolution were shot, beaten and gassed, and bodies would be found in the waterways weeks after the marches ended.

“The killing of a monk was so transgressive an act, it was impossible to ignore,” Østergaard recalled. “It proved that the generals weren’t politicians. They were gangsters — plutocrats — whose primary goal was personal enrichment. They were willing to massacre their own people to protect themselves and their interests.”

The generals were motivated by same things as Al Capone or any other gangster: wealth and the power to keep it.

Although the Burmese people live poorly today, Britain considered Burma to be one of its most profitable colonial assets. For the last 40 years, the generals have gotten fat by controlling exports of timber, gems, oil, natural gas and, of course, opium and heroin from the Golden Triangle. Alone among the world’s great trading nations, China, Singapore, South Korea, India and Thailand have agreed to play ball with the generals. China and Russia supply the military with the arms it needs to terrorize the citizenry.

By restricting the media after the slaughter of students and activists in 1988, Østergaard said, “the generals hoped the world would forget Burma and Burmese would forget themselves.”

Indeed, early in the film Joshua states, “There’s nothing left from ’88. It’s as if everything has been forgotten. Aung San Suu Kyi is in house arrest in the middle of Rangoon. She is in the house, but you cannot go there and talk to her.

“There is just darkness. I feel the world is forgetting about us. That’s why I decided to become a video reporter. At least, I can show that Burma is still here”

It also explains why the generals insisted on changing the name of the country and its major cities, in 1989, and, in 2005, moved the capital from Rangoon to the newly founded city of Naypyidaw. Compared to the more loosely organized and populous commercial hub, Naypyidaw was a bunker.

“No one goes there, unless they have a good reason,” said Khin Maung Win, a founding member of the DVB, who was active in both the 1988 and 2007 protests. “People outside Burma weren’t familiar with ‘Myanmar,’ and, when it began to be picked up in the media, the change confused them.”

Moreover, “Moving the military barracks to Naypyidaw served to isolate the soldiers, who were mostly from rural areas and as poor as everyone else. They’ve been repressed, too.”

Twenty years later, most official world bodies and news organizations remain divided on which name to use. When Cyclone Nargis devastated the country last year, it’s a safe bet that most people hearing the news had no idea where Myanmar was.

“We still use ‘Burma,’” added Win, who spent 12 years in jail after the 1988 demonstrations. “because that’s what people know.”

In several of the scenes captured by VJ Joshua, it appears as if almost everyone in the crowd was carrying a camera-equipped cellphone or holding a handi-cam above their heads. Even if a large percentage of those cameras were being wielded by police and intelligence officers, it shows that the government wasn’t holding all the cards during the Saffron Revolution.

“Things were more chaotic in Burma, than it was in East Germany or, now, in North Korea, where it’s impossible to get these kinds of images,” Østergaard emphasized. “Its borders are more porous, and the ready ability of telecommunications equipment provided opportunities that no longer exist. At first, the intelligence agencies couldn’t handle the chaos.

“The DVB had huge popular support. Everybody knew about the satellites and underground channels.”

Not long after the protests were quashed, key safe houses were discovered by police and shut down. The government also cut off access to the Internet and foreign media. When, less than a year later, Cyclone Nargis wreaked havoc on the country, the generals refused access to journalists and relief organizations. (The junta accepted the contributions, but only if the aid workers weren’t attached.)

“There’s more repression, now, but the world can no longer can pretend it doesn’t know what’s going on in Burma,” said Win.

Concludes Østergaard, “This movie is about people battling their fears,” so others can see the truth.

No better exemplar of such courage is Suu Kyi, whose appearance at the gateway of her home in Burma VJ is one of the film’s highlights.

To find out more about Burma and watch Democratic Voice of Burma, visit its website http://english.dvb.no/about.php. Since most American newspapers and TV networks no longer cover international affairs, the BBC (http://news.bbc.co.uk/) probably has the best mainstream site to follow the trial of Aung San Suu Kyi.

– Gary Dretzka

May 21, 2009