By Gary Dretzka Dretzka@moviecitynews.com

‘Compliance’ stirs emotions by putting viewers in hot seat

At a time when most mega-budget movies are forgotten 10 minutes after the final credits have rolled, it’s interesting that a no-frills indie has kept serious movie buffs talking since it was screened last January at Sundance. Based on a series of actual events, “Compliance” describes just how hideously wrong things can go when otherwise level-headed Americans think they’re doing the right thing.

As near as I can determine, the currently raging controversy derives from Craig Zobel’s determination to lay out the facts of a headline-making invasion of privacy, leaving viewers to decide for themselves if they would have done the same thing under the same circumstances. Zobel raises the emotional ante, as well, by graphically portraying the humiliation suffered by the victim of what was, essentially, prank phone call. Instead of asking the harried manager if she “has Prince Albert in the can?” or “Is your refrigerator running?,” as previous generations of juvenile pranksters have done, the disembodied voice demanded something far more terrifying.

“It’s a rough subject and ‘Compliance’ is an intentionally challenging movie,” Zobel concedes. “It goes to the question of what we expect movies to do. The response we’ve gotten since Sundance, where some people booed and walked out, has been more positive.”

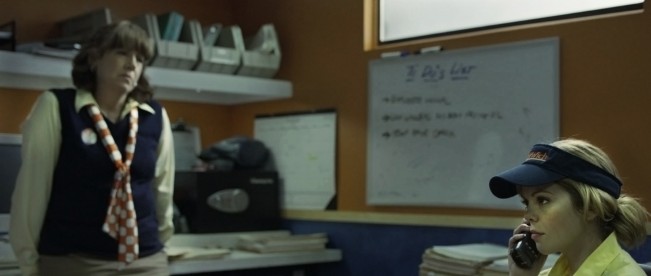

By invoking the authority of the local police department, the caller asks the manager, Sandra (Ann Dowd), to conduct a strip search of an employee he accuses of theft. The faux cop says he is too busy to conduct the examination himself, so, in effect, he would be willing to deputize Sandra to get to the truth. Instead, he toys with her willingness to serve the public by demanding she dehumanize the girl and recruit accomplices to add to her misery.

To varying degrees of gullibility, they all follow suit. None bothers to recall what they’d observed from watching hundreds of episodes of “Law & Order,” “The People’s Court” or even “Dragnet.” In the post-9/11 era, they may have assumed, as well, that the Patriot Act applies as much to purse snatchers as terrorists. If Zobel’s conceit sounds far-fetched, you should know that the prank was successfully pulled off at least 70 times in the previous 12 years.

Anyone who thinks they’re too hip or sophisticated to fall for such a ruse may want to ask themselves if they bought the Bush-Cheney theory about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, President Obama’s pledge to punish the perpetrators of the ongoing financial disaster or the findings of the Warren Report. Compared to these whoppers, falling for a guy impersonating a police officer – in person at a traffic stop or via a phone call – is small potatoes.

“We all have a moral compass, but it isn’t always clear to us how delicate it is,” Zobel says. “In our society, there’s an implicit social contract between citizens and the police that they’re going to do the right thing. But, it’s true that people of different racial and ethnic backgrounds will see things differently when it comes to police.”

Make no mistake about it, “Compliance” packs the same punch as the horror genre’s most effective examples of “torture porn.” Watching an inarguably innocent teenager being forced to strip by her supervisor and probed by the woman’s boyfriend, however reluctant, isn’t for the squeamish. Not only do we cringe for the victim, but we also sympathize with the manager, who probably was raised to respect the local police force without question. After all, in many parts of the United States, racial profiling and the use of torture to extract confessions represent either legitimate police work or a myth perpetrated by the ACLU.

“I think we were able to capture the feeling that Becky was defenseless throughout her ordeal and Sandra was just trying to get through the day,” Zobel adds. “Naturally, most viewers will respond, ‘I wouldn’t do that.’ But, deep down, everyone wants to be a hero.”

Indeed, it’s entirely possible that the lunatic who went on a shooting spree at a Sikh temple two weeks ago, in Wisconsin, mistakenly assumed the victims’ turbans represented an affiliation with Al Qaeda. In his delusional mind, he must as felt as if he was doing the right thing and should be regarded as an American hero. He wasn’t the first self-styled patriot to mistake a Sikh with a Muslim, with the same deadly result.

Indeed, it’s entirely possible that the lunatic who went on a shooting spree at a Sikh temple two weeks ago, in Wisconsin, mistakenly assumed the victims’ turbans represented an affiliation with Al Qaeda. In his delusional mind, he must as felt as if he was doing the right thing and should be regarded as an American hero. He wasn’t the first self-styled patriot to mistake a Sikh with a Muslim, with the same deadly result.

Zobel is no stranger to the world of long and short cons. In 2007’s “Great World of Sound,” he dramatized an elaborate scheme in which a pair of sharp operators convinced dozens of mostly tone-deaf singers that, in exchange for a considerable sum of money, they would record the rubes and find a market for the songs. By the time the con artists split town, the victims would be left with a poorly recorded song and dashed hopes. In that movie, Zobel placed ads in local papers to lure “American Idol” wannabes to faux auditions and mixed their sessions with those using actors and reasonably good singers. The effect was similarly creepy, if not nearly as horrifying as the actions portrayed in his new film.

“Compliance” is based on the April 2004 incident a fast-food restaurant in Mount Washington, Kentucky, with an Ohio “ChickWich” standing in for McDonald’s. Although the caller (Patrick Healy) probably wasn’t aware of the fact that the ChickWich was understaffed and short of certain staples that night, he logically guessed (or learned from surveillance) that a pretty blond, Becky (Dreama Walker), would be manning the counter and make an ideal suspect. Sandra inadvertently fills in the blanks for the caller.

Zobel is able to establish credibility by dramatizing the logistics of operating a fast-food franchise during a busy part of the day. Sandra’s already freaked out by the likelihood that a company inspector may be paying a visit on this of all nights. When she fields the prank call, it becomes one of several balls she’s juggling.

Despite the fact that Becky continually denies the accusation, Sandra agrees to take her to a storage room, where the strip search would be captured on a surveillance camera. The alternative would be having Becky arrested, driven to the police station and booked, regardless of the absence of evidence. It would have been the correct procedure, but Sandra felt as if she were protecting both her employee and the franchise’s reputation.

She compounds the injustice by asking other employees to watch Becky when duty called her to the kitchen. Worse, she enlists her fiancé to stand guard. The caller convinces him of the necessity of demanding a sexual act from Becky. In real life, a guilty conscience led the man to confess his compliance to a friend, who alerted police to what was happening just down the road from them.

“Only one caller was brought to justice in all of the cases,” Zobel says. “He wasn’t convicted, but the calls stopped. There were civil and class-action suits brought against the manager and restaurant chains.

“It was difficult to determine the degree of responsibility each party should shoulder. There was one large settlement, at least, and a clarification of company guidelines.”

After Becky is thoroughly humiliated and, likely, traumatized for life, it’s clear that Zobel is referencing the experiments conducted in the early 1960s by Yale psychologist Stanley Milgram and Stanford prison experiment of 1971. In both cases, participants representing law-enforcement interests went to extreme lengths to get volunteer subjects and prisoners to conform to an established norm.

Detractors have argued that Zobel’s decision to linger on Becky’s humiliation degrades the character and provokes the prurient interests of some male viewers. How else, though, to characterize exactly what was at stake in the actual crimes? If we aren’t made to squirm by the willingness of the manager to act as a surrogate for the pervert on the other end of the call, would we be as disturbed to learn that the man arrested for the prank was acquitted due to lack of evidence and, in a postscript, Sandra continues to excuse her own behavior?

Detractors have argued that Zobel’s decision to linger on Becky’s humiliation degrades the character and provokes the prurient interests of some male viewers. How else, though, to characterize exactly what was at stake in the actual crimes? If we aren’t made to squirm by the willingness of the manager to act as a surrogate for the pervert on the other end of the call, would we be as disturbed to learn that the man arrested for the prank was acquitted due to lack of evidence and, in a postscript, Sandra continues to excuse her own behavior?

In any case, Zobel didn’t intend for “Compliance” to be mistaken for an entertaining night at the local arthouse. Anyone expecting something a bit more uplifting might want to follow their moral compass in the direction of Spike Lee’s “Do the Right Thing” before confronting the ethical morass that is “Compliance.”