By Jake Howell jake.howell@utoronto.ca

Cannes Reviews: The Hunt, Room 237

Cannes Competition review: The Hunt

Thomas Vinterberg’s Jagten, otherwise known as The Hunt, is Danish drama at its damnedest. I’m happy to announce that the Festen director is finally relevant again, despite having spotty success since his celebrated Dogme 95 contributions, because The Hunt features an absolutely dynamite story that shocks, angers, and thoroughly engrosses. Additionally, a la The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, the film exhibits classic construction and superb, straight-forward exposition, meaning a Hollywood remake could be around the corner. (Let’s hope that doesn’t happen.)

The Hunt is narratively similar to Festen in its theme of child molestation. Whereas Festen’s was all too real, The Hunt’s pedophilia is entirely fabricated: the child abuse is a lie propagated by 5-year-old Klara, who doesn’t understand the power of her words. In this battle of confusion and misinformation, it’s the child’s lie against the adult’s protest, and that’s a game with horrible odds. Lucas is an outstanding citizen, a caring father, and a beloved member of his small-town community prior to the accusation, but his credibility is completely shattered as a result of the ordeal, which becomes a test of faith for all parties. Luckily, a small group of people believe Lucas is innocent, and support him with hilarious quips about the absurdity of the situation. The comic relief in The Hunt is perfectly timed and always appreciated.

The Hunt is narratively similar to Festen in its theme of child molestation. Whereas Festen’s was all too real, The Hunt’s pedophilia is entirely fabricated: the child abuse is a lie propagated by 5-year-old Klara, who doesn’t understand the power of her words. In this battle of confusion and misinformation, it’s the child’s lie against the adult’s protest, and that’s a game with horrible odds. Lucas is an outstanding citizen, a caring father, and a beloved member of his small-town community prior to the accusation, but his credibility is completely shattered as a result of the ordeal, which becomes a test of faith for all parties. Luckily, a small group of people believe Lucas is innocent, and support him with hilarious quips about the absurdity of the situation. The comic relief in The Hunt is perfectly timed and always appreciated.

Lucas is played by Mads Mikkelsen, who most North Americans will remember as the most entertaining Bond villain in recent memory, Le Chiffre (2006’s Casino Royale). Since then, it’s been a joy to see Mikkelsen’s career gain a massive amount of momentum and star power, as it’s plain to see his ability and range as an actor. While The Hunt gives the talented Dane almost all of the screen time, the other members of his community – most of them played by non-actors – function appropriately and believably, whether they judge blindly or withhold their assumptions.

For better or for worse, The Hunt can be very a frustrating drama. This is because Lucas is violently unwelcome wherever he goes, but the audience knows Lucas is innocent the whole time. Many of these encounters become infuriatingly hard to watch, because of how wrong his attackers are. That’s a good thing. Great writing – and this is an downright monster of a story – necessarily involves evoking emotional responses, and The Hunt could make you very angry. Maybe not at the film, but at the situation, the lies, and the uneasiness of how possible this could ruin someone. If this is the case, and audiences are upset during The Hunt, I’d conclude the film is an overarching success based purely in its exploration of overreactions.

Fortunately, Lucas is also unwaveringly resilient, and he always fights back most righteously. For example, one scene involving a grocery store clerk – with a delivery that channels the likes of Quentin Tarantino’s work – will have audiences clapping and cheering at the screen. The film as a whole is an electrifying commentary on society and the result of mass hysteria, and will enthrall audiences who enjoy traditional narrative storytelling. There’s even a mystery involved, which keeps Lucas – and everyone watching – in constant fear for his life.

Fortunately, Lucas is also unwaveringly resilient, and he always fights back most righteously. For example, one scene involving a grocery store clerk – with a delivery that channels the likes of Quentin Tarantino’s work – will have audiences clapping and cheering at the screen. The film as a whole is an electrifying commentary on society and the result of mass hysteria, and will enthrall audiences who enjoy traditional narrative storytelling. There’s even a mystery involved, which keeps Lucas – and everyone watching – in constant fear for his life.

There is one potential deal breaker in The Hunt, which could undermine everything that occurs in its narrative: Lucas doesn’t exactly do much to help his case, other than insist he’s innocent and stand by the strength of his upstanding character. Some viewers may find themselves internally screaming at Lucas to properly elucidate what actually happened, because he may have been able to explain to his community why Klara lied in the first place. Then again, it’s just as plausible the town at large wouldn’t believe it anyway. In fact, there’s a scene with Klara admitting to her “silly” lie, and the audience watches as Klara’s mother dismisses it as an invention of her imagination. The urge to rage at certain characters is instinctive, and it speaks to the strength of how affecting the story is. Viewers may come away from The Hunt complaining the narrative artificially evolves, but the depictions of public scandal, commotion, and Lucas’ witch hunt are persuasively possible. If audiences buy what Vinterberg is selling – and I sincerely hope they do, perhaps after an extremely likely Best Foreign Language Oscar nomination – they will be treated to an overwhelmingly rattling narrative that hits very, very close to home.

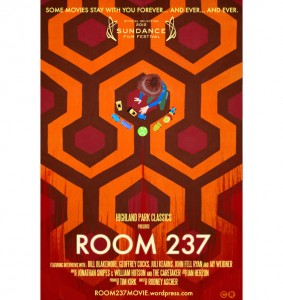

Cannes Director’s Fortnight review: Room 237

At face value, Room 237 is a neat little documentary about the many hidden meanings in the Kubrick adaptation of the Stephen King’s beloved horror novel The Shining. It’s an excellent film that exhibits some truly interesting theories about its subject matter, and the result is a unique, crackerjack doc that has multiple layers of depth and complexity.

Room 237’s main theme is authorial intent, because the film is informed by people (read: fans) who have read into Stanley Kubrick’s directorial mind to see what they want to see in The Shining. Most of the theories these fans present are crazy, but some of them have hints of validity. However, while almost all of the theories are tenuous, Room 237 employs frame-by-frame scene analysis to help keep these extraordinarily kooky ideas interesting and entertaining. Rationally-inclined audiences will (and should) take these ideas with a mountain of salt, but there is a lot of fun to be had with Room 237. You come away from the film thinking there is probably something lurking beneath the surface of The Shining’s horror narrative, even if it isn’t a global conspiracy. I  don’t want to mention specifically what is discussed, because the narrators can do it themselves. Just note that their ideas are wacky, weird, and wonderful, and telling you about them would ruin the magic of Room 237.

don’t want to mention specifically what is discussed, because the narrators can do it themselves. Just note that their ideas are wacky, weird, and wonderful, and telling you about them would ruin the magic of Room 237.

Many – if not all – of these claims will cause eyes to roll, but that doesn’t really matter, because it makes no difference to the novelty of Room 237 if you have particular difficult handling one or more of the ideas. They are only secondary to the viewing of this film, because Room 237 is not about The Shining.

Fine, yes – Room 237 technically is very focused on Kubrick’s classic horror film, but the main concern is The Shining’s fans, not the film itself. In other words, I don’t think Room 237 is a documentary highlighting new or interesting truths about an iconic movie. Instead, I’d argue the doc is primarily about obsessive fan culture; i.e., how the Internet propagates theories, how home entertainment allows fans to dissect films by pausing whenever they want, and how some people get entirely too caught up in their findings. The theorists in Room 237 are fascinating to listen to, but when you realize they’ve been pouring over The Shining for decades to produce outlandish readings of both the movie and its author, the film registers as something more than just a film about hidden symbolism in popular culture. Calling these people “freaks” would be wrong – people have obsessions, and that’s totally okay – but to say Room 237 is about The Shining is I think missing the point. The film is a documentary about five theorists, and it isn’t really their ideas that make them interesting people. Rather, it’s how far they’ve gone as fans.

Perhaps I’m wrong, but I asked producer Tim Kirk what he thought of my idea, to which he smiled and said “I think that’s a totally fair reading of the film”. So thank you Mr. Kirk, and thank you director Rodney Ascher, for embracing the irony of having viewers discuss authorial intent, be it latent or overt, on a film conceivably about authorial intent. You have my respect, sirs.

Room 237 is a remarkable movie (with equally remarkable original music that is funky and haunting), and is like kind of what mash-up artist Girl Talk would do if he ever made a movie. There are no talking heads in Room 237 – all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy – because Ascher is too busy showing you bits of archival footage, other movies, and most importantly clips of The Shining to ever show what these narrators look like. The documentary is bizarrely cool, and one I hope to see again as soon as possible (after, of course, re-watching a certain horror movie).

Jake Howell has a great deal to say about Room 237 that hits the mark, but as one of the voices in The Shining I must argue for the substance of my analysis of a Holocaust subtext in The Shining. Bill Blakemore and I have taken a close look at a film that deserves a close look because Kubrick’s films are always about larger issues, particularly historical ones. Bill is right that there is a visual discourse in The Shining concerning the decimation of Native Americans by European invaders, which dovetails with the visual and aural evidence concerning the Holocaust I have found not only in this film but other Kubrick films, and the history surrounding Kubrick’s lifespan. While I, like Bill, admire Kubrick as an artist, I am not a “fan” in the sense that I am “obsessed” with the film as some sort of mirror of my own discontents. Rather, as a historian of modern Germany and Europe, I am interested in the film as one particular artist’s manner of commenting on the major historical tragedies of the Third Reich and the Final Solution. Director Kubrick was a master of indirection and that is what make his films such rich vehicles of thought and expression. That does not mean that anything goes in interpretation. For example, I see no evidence inside or outside of this film that Kubrick faked film of the moon landing.

Hi Geoffrey,

thank you for your thoughtful comment. That’s very interesting, indeed – I think it says much about the film as a whole if it is fostering all of this healthy discussion. Good luck to you, sir.