By Jake Howell jake.howell@utoronto.ca

Routing Cannes 66: A Wrap

In an unprecedented move, the Steven Spielberg-led jury awarded the Palme d’Or to one film and three individuals: Blue is the Warmest Color, by director Abdellatif Kechiche with actresses Adèle Exarchopoulos and Lea Seydoux.

This skirted the festival’s rule of preventing a sweep, as a film in Competition at Cannes cannot win both a major award and an acting prize. A respectable decision, as Blue is the Warmest Color (La Vie d’Adèle) is a cinematic achievement in exceptional performance. Do not miss it.

Remember the name: Adele Exarchopoulos. An actor since 2007 (2007’s Boxes, 2010’s La Rafle), the 19-year-old has managed to secure one of the film world’s most prestigious awards with her staggering role as La Vie d’Adèle’s title protagonist. It’s the biggest, most important film at this festival, filled with life and political relevance. A true opus; one that needed to win, some say, to avoid censorship (the film locks in at a three-hour runtime, avec explicit sex). Ideally, the version shown for Cannes audiences is the same version eventually seen outside of the Croisette (unless Kechiche makes his own trims, as has been rumored).

Remember the name: Adele Exarchopoulos. An actor since 2007 (2007’s Boxes, 2010’s La Rafle), the 19-year-old has managed to secure one of the film world’s most prestigious awards with her staggering role as La Vie d’Adèle’s title protagonist. It’s the biggest, most important film at this festival, filled with life and political relevance. A true opus; one that needed to win, some say, to avoid censorship (the film locks in at a three-hour runtime, avec explicit sex). Ideally, the version shown for Cannes audiences is the same version eventually seen outside of the Croisette (unless Kechiche makes his own trims, as has been rumored).

The other winners are just as fun. The Grand Prix—second place—was given to Inside Llewyn Davis, presumably because of the wonderful Oscar Isaac and the meticulous direction by the unstoppable Coen Brothers. Let it be known that their newest film has cracked my personal top-three list of their work.

The other winners are just as fun. The Grand Prix—second place—was given to Inside Llewyn Davis, presumably because of the wonderful Oscar Isaac and the meticulous direction by the unstoppable Coen Brothers. Let it be known that their newest film has cracked my personal top-three list of their work.

There’s always a surprise at the Cannes awards, and this year’s shocker was the winner of Best Director, Amat Escalante. Heli, Escalante’s third feature, was probably the subject of a political move: poorly-received by most critics (myself excluded), the film’s depiction of Mexico’s tragic drug violence struck a chord with the jury. No matter: Heli is a fine film, regardless of its difficult scenes. (Escalante’s mentor, Carlos Reygadas, won the same prize last year for Post Tenebras Lux.)

There’s always a surprise at the Cannes awards, and this year’s shocker was the winner of Best Director, Amat Escalante. Heli, Escalante’s third feature, was probably the subject of a political move: poorly-received by most critics (myself excluded), the film’s depiction of Mexico’s tragic drug violence struck a chord with the jury. No matter: Heli is a fine film, regardless of its difficult scenes. (Escalante’s mentor, Carlos Reygadas, won the same prize last year for Post Tenebras Lux.)

In third place is Hirokazu Kore-Eda’s Like Father, Like Son, winner of the Jury Prize. The film was an expected favorite, especially given its themes that many thought were sure to please Steven Spielberg, a man of family narratives (as well as a large family). It was a safe bet, too: with great acting across the board (including the kids, who really needed to sell the picture more than anyone else), it seemed impossible it would walk away from the festival empty-handed.

In third place is Hirokazu Kore-Eda’s Like Father, Like Son, winner of the Jury Prize. The film was an expected favorite, especially given its themes that many thought were sure to please Steven Spielberg, a man of family narratives (as well as a large family). It was a safe bet, too: with great acting across the board (including the kids, who really needed to sell the picture more than anyone else), it seemed impossible it would walk away from the festival empty-handed.

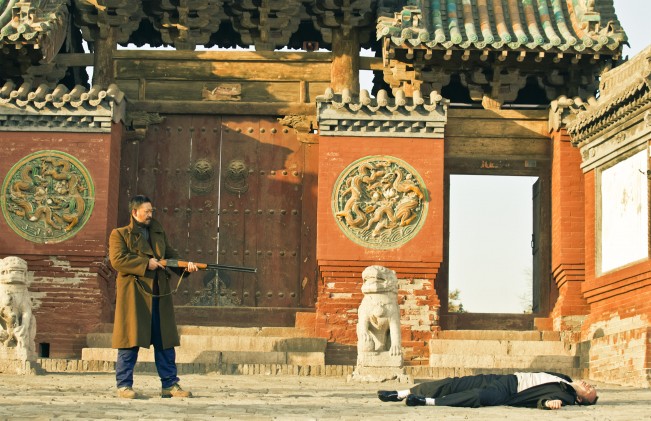

Best Script was given to Jia Zhang-Ke, director of A Touch of Sin. Highly critical of contemporary China, Zhang-Ke’s intertwined quarter of narratives was a violent, broadly appealing film and the most “mainstream” venture in his filmography. A justified win, even though most thought him to win the Best Director prize. Given its boldness, A Touch of Sin had to win something.

Best Script was given to Jia Zhang-Ke, director of A Touch of Sin. Highly critical of contemporary China, Zhang-Ke’s intertwined quarter of narratives was a violent, broadly appealing film and the most “mainstream” venture in his filmography. A justified win, even though most thought him to win the Best Director prize. Given its boldness, A Touch of Sin had to win something.

The Best Actor race was all but sewn up: with fantastic performances from Oscar Isaac (Inside Llewyn Davis) and Matt Damon and Michael Douglas (Behind the Candelabra), the front-runners were clear. But the Jury decided to laud Isaac (and the Coens) with the Grand Prix, thus barring Isaac from the acting prize. Instead, the jury went elsewhere, awarding the sweepstakes to Bruce Dern in Alexander Payne’s Nebraska. Dern does a fine job as Nebraska’s lovable codger.

The Best Actor race was all but sewn up: with fantastic performances from Oscar Isaac (Inside Llewyn Davis) and Matt Damon and Michael Douglas (Behind the Candelabra), the front-runners were clear. But the Jury decided to laud Isaac (and the Coens) with the Grand Prix, thus barring Isaac from the acting prize. Instead, the jury went elsewhere, awarding the sweepstakes to Bruce Dern in Alexander Payne’s Nebraska. Dern does a fine job as Nebraska’s lovable codger.

In truth, Best Actress was one of the hardest awards to call. There were many excellent female performances, including Hadewych Minis (Borgman), Carey Mulligan (Inside Llewyn Davis), Marine Vacth (Jeune et Jolie) , Marion Cotillard (The Immigrant), Kristin Scott Thomas (Only God Forgives) and even June Squibb (Nebraska). The critical front-runners, however, were Bérénice Bejo (The Past), Emmanuelle Seigner (Venus in Fur), and the leads of Blue is the Warmest Color. The finest female performances were indisputably in the latter (leading to a Palme d’Or win), so the jury went for the César-winner Bejo. Asghar Farhadi’s follow-up to A Separation is expectedly very strong, and Bejo’s performance did much for the film’s success.

In truth, Best Actress was one of the hardest awards to call. There were many excellent female performances, including Hadewych Minis (Borgman), Carey Mulligan (Inside Llewyn Davis), Marine Vacth (Jeune et Jolie) , Marion Cotillard (The Immigrant), Kristin Scott Thomas (Only God Forgives) and even June Squibb (Nebraska). The critical front-runners, however, were Bérénice Bejo (The Past), Emmanuelle Seigner (Venus in Fur), and the leads of Blue is the Warmest Color. The finest female performances were indisputably in the latter (leading to a Palme d’Or win), so the jury went for the César-winner Bejo. Asghar Farhadi’s follow-up to A Separation is expectedly very strong, and Bejo’s performance did much for the film’s success.

Finally, I want to thank you for reading, whether it was the neurotic pre-festival write-ups or my reviews as the festival played out. I’m happy to report that somehow, the most impressive movies this year in Competition were given the awards and international press they deserved. One can only hope these highlights find distribution near you very soon.

À la prochaine.

Other winners:

Short Film Palme d’Or: Safe, by Byoung-gon Moon

Short Film special mention: Whale Valley, by Guðmundur Arnar Guðmundsson.

Camera d’Or: Ilo Ilo, by Anthony Chen (playing in the Director’s Fortnight).

Excellent review of the festival. I wonder why there’s a rule to preven a sweep. So Emmanuelle Riva would have not win for “Amour” last year?

Nice job Jake. You called the Palme d’Or the minute the press screening ended.

Gonzalo: I have a feeling last year’s jury gave Amour the Palme d’Or to laud the exquisite performances. The film was carried by Riva and Trintignant, so giving the film the Palme was the same as giving them Best Actress and Best Actor.

Jay: it hit all the right notes. Thanks very much.

Gonzalo,

I think the reason for the ruling is because in 1991, Barton Fink won no less than three. Palme d’Or, Best Director and Best Actor. And most people suspect the reason why it won Best Director was because at the time, the Coens split their credits with Joel directing and Ethan producing. So rather than give one brother an award and ignore the other, they gave them one each. Of course, it helped that Barton Fink is a brilliant film and that year, the only other film that was in serious contention was Jacques Rivette’s La Belle Noiseuse.

I could be wrong, but I suspect that is the reason.