By Ray Pride Pride@moviecitynews.com

Best of 2014: A Top 40

1. Boyhood, Richard Linklater. Linklater is one of the few filmmakers you’d expect to foresee the fact that he would be shooting a period piece in the present: that is, that each year would be seen from a distance of years, and however the present was characterized, through pop culture and other social artifacts, would accrue into simple nostalgia. But Linklater’s better than that, and the ending, the very ending, is open-ended yet also a summation of what so many of his wanderers have been searching for all their on-screen lives. Boyhood is perfectly imperfect, and surely not the last exploration of feature filmmaking as the ideal form to encapsulate duration and unities of location to come from the dogged, invaluable fifty-three-year-old writer-director. Time. Time itself. As much as any of Linklater’s movies, Boyhood fits squarely into the exquisite expanses of one of my favorite poems, my fellow Kentuckian Robert Penn Warren’s “Audubon: a vision”:

1. Boyhood, Richard Linklater. Linklater is one of the few filmmakers you’d expect to foresee the fact that he would be shooting a period piece in the present: that is, that each year would be seen from a distance of years, and however the present was characterized, through pop culture and other social artifacts, would accrue into simple nostalgia. But Linklater’s better than that, and the ending, the very ending, is open-ended yet also a summation of what so many of his wanderers have been searching for all their on-screen lives. Boyhood is perfectly imperfect, and surely not the last exploration of feature filmmaking as the ideal form to encapsulate duration and unities of location to come from the dogged, invaluable fifty-three-year-old writer-director. Time. Time itself. As much as any of Linklater’s movies, Boyhood fits squarely into the exquisite expanses of one of my favorite poems, my fellow Kentuckian Robert Penn Warren’s “Audubon: a vision”:

Tell me a story.

In this century, and moment, of mania,

Tell me a story.

Make it a story of great distances, and starlight.

The name of the story will be Time,

But you must not pronounce its name.

Tell me a story of deep delight.

2. Gone Girl, David Fincher. The hyperbolic, galvanic, filthy-black-funny Gone Girl is multitudes. And it’s one of the most complexly disturbing movies about grownups fucking up sex in all too long. Sex, no, not sex, really, but power. Who has the fucking upper hand and who has the upper hand fucking? (Oh, the music in Rosamund Pike’s voice when her “Amazing Amy” first beds Nick and says, as he tousles his face upon her lap in an act of assured cunnilingus, “Nick Dunne, I really like you.”) And every bit of it is so readily read into, and not limited to various and sundry accusations of misogyny in the narrative. Gone Girl is unreliable narration atop unreliable narration. A second viewing was nearly as unnerving as the first: there’s three sides to every story, yours mine and the cold, hard truth; Fincher and Flynn have their cake, your cake and eat it too, in meta-meta commentary of the modern moment of media and what none dare call “relationships.” Cut at a sweetly punishing clip, Gone Girl refracts so many attitudes about the cupidity of human desire and the rapidity of the fall when attempts to fuck up another person fuck you up in turn.

3. The Immigrant, James Gray. Where Bruno binds Ewa to bed and pulls her to ground, speaking always of cash, Emil climbs in windows through fire escapes, brandishes postcards of the beautiful California seaside (which, cannily, we are not allowed to glimpse) and at one inexplicable moment of implausible, fantasticated beauty, merely levitates. In a world of soot and muck and views warped by crudely annealed, light-bending, feature-distorting window glass, Emil promises life can become lighter than air, where once all that is profaned could become sacred once more. While the locations and panoramas are limited (to effective budgetary and esthetic effect), the ghostly dreaminess of The Immigrant lies in its realization of the state of mind of its characters, each imbued with hope no matter how quickly they become a “soiled dove,” as Bruno coos at Ewa. These are the ones that had a hope that was handed down to generations. And yet we know that when Emil says in one of his performances, “Don’t give up the faith, don’t give up the hope, the American Dream is waiting for you!” it is as much threat as promise, but it is a threat and promise upon which our America, now, is built. It is a brilliant rebuke to the making of myth. Its heart is pure.

3. The Immigrant, James Gray. Where Bruno binds Ewa to bed and pulls her to ground, speaking always of cash, Emil climbs in windows through fire escapes, brandishes postcards of the beautiful California seaside (which, cannily, we are not allowed to glimpse) and at one inexplicable moment of implausible, fantasticated beauty, merely levitates. In a world of soot and muck and views warped by crudely annealed, light-bending, feature-distorting window glass, Emil promises life can become lighter than air, where once all that is profaned could become sacred once more. While the locations and panoramas are limited (to effective budgetary and esthetic effect), the ghostly dreaminess of The Immigrant lies in its realization of the state of mind of its characters, each imbued with hope no matter how quickly they become a “soiled dove,” as Bruno coos at Ewa. These are the ones that had a hope that was handed down to generations. And yet we know that when Emil says in one of his performances, “Don’t give up the faith, don’t give up the hope, the American Dream is waiting for you!” it is as much threat as promise, but it is a threat and promise upon which our America, now, is built. It is a brilliant rebuke to the making of myth. Its heart is pure.

4. The Grand Budapest Hotel, Wes Anderson. Anderson’s everyman-in-no-man’s-land is Gustave H., the concierge of an ocean liner of a wedding-cake deluxe hotel in the fictional duchy of Zubrowka, The Grand Budapest Hotel. He is a man with a job, if not a surname or a notable nationality. Ralph Fiennes invests H. with the brusque panache of both the boulevardier and the comic lights of the stage. Lubitsch’s blithe cosmopolitanism is supplanted by brute snippiness in the person of Fiennes. Speaking faster than he fast-walks, his H. is given to “oh fuck it”s that are the verbal equal of Indiana Jones choosing to take out a pistol and dispatch a scimitar-wielding opponent. (Fiennes is nourished by H.’s bursts of comic filth.) His impatience, his hurry, accelerates the sense that a narrative, an era, is hurtling to a close, as well as setting the tempo for the heist-and-chase design of this lovely, if bittersweet accomplishment.

4. The Grand Budapest Hotel, Wes Anderson. Anderson’s everyman-in-no-man’s-land is Gustave H., the concierge of an ocean liner of a wedding-cake deluxe hotel in the fictional duchy of Zubrowka, The Grand Budapest Hotel. He is a man with a job, if not a surname or a notable nationality. Ralph Fiennes invests H. with the brusque panache of both the boulevardier and the comic lights of the stage. Lubitsch’s blithe cosmopolitanism is supplanted by brute snippiness in the person of Fiennes. Speaking faster than he fast-walks, his H. is given to “oh fuck it”s that are the verbal equal of Indiana Jones choosing to take out a pistol and dispatch a scimitar-wielding opponent. (Fiennes is nourished by H.’s bursts of comic filth.) His impatience, his hurry, accelerates the sense that a narrative, an era, is hurtling to a close, as well as setting the tempo for the heist-and-chase design of this lovely, if bittersweet accomplishment.

5. Love Is Strange, Ira Sachs. Drama seeps in, sensation is suggested. The film’s quietly detailed, lived-in, loved-in feel is both emotionally specific and painterly in its suggestive formal sensations. (Sachs cites the work of American painter Fairfield Porter as a key visual touchstone.) Among his cast, which extends two generations, each figure walks in geometry. Each character has a specific fashion of holding space. Love is Strange is about, yes, love, and about family and about the necessity of generations sharing knowledge and secrets, yet there’s not a line of dialogue that announces this. Love is Strange also bears the acuteness, the precision of the era the characters would have lived through. Buried deep beneath the surfaces, surely there are submerged fragments of Frank O’Hara and his fragrant, antic verse as well as the lore of the painters who frequented and illuminated the interior life of lairs like the Cedar Tavern. The succession of setting and framings are beautiful for their precision and coolness, from strong design rather than a prurient glow.

5. Love Is Strange, Ira Sachs. Drama seeps in, sensation is suggested. The film’s quietly detailed, lived-in, loved-in feel is both emotionally specific and painterly in its suggestive formal sensations. (Sachs cites the work of American painter Fairfield Porter as a key visual touchstone.) Among his cast, which extends two generations, each figure walks in geometry. Each character has a specific fashion of holding space. Love is Strange is about, yes, love, and about family and about the necessity of generations sharing knowledge and secrets, yet there’s not a line of dialogue that announces this. Love is Strange also bears the acuteness, the precision of the era the characters would have lived through. Buried deep beneath the surfaces, surely there are submerged fragments of Frank O’Hara and his fragrant, antic verse as well as the lore of the painters who frequented and illuminated the interior life of lairs like the Cedar Tavern. The succession of setting and framings are beautiful for their precision and coolness, from strong design rather than a prurient glow.

6. We Are The Best!, Lukas Moodysson. What brought Moodysson back to the deliriousness of early movies like Show Me Love (Fucking Åmål)? Love. Love for his wife, Coco. Love for her stories of unstemmable punk girlhood. Punk lives! (and how!).

6. We Are The Best!, Lukas Moodysson. What brought Moodysson back to the deliriousness of early movies like Show Me Love (Fucking Åmål)? Love. Love for his wife, Coco. Love for her stories of unstemmable punk girlhood. Punk lives! (and how!).

7. Ida, Paweł Pawlikowski. There are surely ample footnotes to be made about photographic influence, but what matters is what has been made from influence: a movie that feels like it is a window looking into the distant past, in a format and fashion akin to its era, but which also feels contemporary, timeless and never anachronistic. It is a movie in its moment, but also of its moment: Pawlikowski, and only Pawlikowski, could only have made it in this moment. Shot to shot, each and every element thrills. While the non-actor Agata Trzebuchowska is superb in indicating near-silent acknowledgment of all that swirls around her, Agneta Kulesza, with superlative presence, is the star of the show in every frame she enters or exits, electric with boundless passion, heedless fury, thwarted hope, vital cynicism passed from cigarette end to cigarette end.

7. Ida, Paweł Pawlikowski. There are surely ample footnotes to be made about photographic influence, but what matters is what has been made from influence: a movie that feels like it is a window looking into the distant past, in a format and fashion akin to its era, but which also feels contemporary, timeless and never anachronistic. It is a movie in its moment, but also of its moment: Pawlikowski, and only Pawlikowski, could only have made it in this moment. Shot to shot, each and every element thrills. While the non-actor Agata Trzebuchowska is superb in indicating near-silent acknowledgment of all that swirls around her, Agneta Kulesza, with superlative presence, is the star of the show in every frame she enters or exits, electric with boundless passion, heedless fury, thwarted hope, vital cynicism passed from cigarette end to cigarette end.

8. Calvary, John Michael McDonough. Calvary is, in a very specific way, a “B” movie, by which I mean, “Bergman, Buñuel and Bresson,” Ireland, day: Man walks into a confession booth and tells a priest of terrible things that had been done to him by a priest when he was small. Tells the priest: I’ll get back at the church by killing an innocent priest in one week, and that’s you, get your life in order. Now there’s a set-up. The second feature by writer-director John Michael McDonagh, fills that week full-to-bursting with a raft of idiosyncratic characters and philosophical conflicts and the current crisis in the Church and idiomatic comic dialogue strung along by the script’s thriller-like ticking clock. Brendan Gleeson’s Father James could very well be his best performance in a great career. (Gleeson told me it’s his favorite role.) Graham Greene divided his books into two classes: the novels, which took on spiritual matters, and the lighter ones, which he called “entertainments.” McDonagh’s knack is to combine both the novelistic, spiritual elements of Greene and lighter notes to achieve a high level of gratifying entertainment.

8. Calvary, John Michael McDonough. Calvary is, in a very specific way, a “B” movie, by which I mean, “Bergman, Buñuel and Bresson,” Ireland, day: Man walks into a confession booth and tells a priest of terrible things that had been done to him by a priest when he was small. Tells the priest: I’ll get back at the church by killing an innocent priest in one week, and that’s you, get your life in order. Now there’s a set-up. The second feature by writer-director John Michael McDonagh, fills that week full-to-bursting with a raft of idiosyncratic characters and philosophical conflicts and the current crisis in the Church and idiomatic comic dialogue strung along by the script’s thriller-like ticking clock. Brendan Gleeson’s Father James could very well be his best performance in a great career. (Gleeson told me it’s his favorite role.) Graham Greene divided his books into two classes: the novels, which took on spiritual matters, and the lighter ones, which he called “entertainments.” McDonagh’s knack is to combine both the novelistic, spiritual elements of Greene and lighter notes to achieve a high level of gratifying entertainment.

9. Winter Sleep, Nuri Bilge Ceylan. Ceylan’s usual cinematographer, Gokhan Tiryaki, fixes on landscape in interiors as well as exteriors: he and Ceylan are patient poets of the human face.

9. Winter Sleep, Nuri Bilge Ceylan. Ceylan’s usual cinematographer, Gokhan Tiryaki, fixes on landscape in interiors as well as exteriors: he and Ceylan are patient poets of the human face.

10. Actress, Robert Greene. Life as performance, personality as melodrama, persona as hope. This is the film I’d hoped a filmmaker as intelligent and driven as Robert Greene would make someday, but so soon? His intimate collaboration with his neighbor, actress and mother Brandy Burre is a dazzling singularity, a film to be seen and seen again as much as described to whomever you’re watching it with next.

10. Actress, Robert Greene. Life as performance, personality as melodrama, persona as hope. This is the film I’d hoped a filmmaker as intelligent and driven as Robert Greene would make someday, but so soon? His intimate collaboration with his neighbor, actress and mother Brandy Burre is a dazzling singularity, a film to be seen and seen again as much as described to whomever you’re watching it with next.

11. Citizenfour, Laura Poitras. Edward Snowden’s loquacity in describing the responsibility of a governed citizenry, as well as the elemental passion he expresses for American ideals, stand in stark contrast to the grandstanding of onscreen politicos and spooks, and elevate what could be merely technical talk about “metadata in aggregate” and how billions of conversations could be (and are) siphoned into the data coffers of the government and its contractors each day to something approaching manifesto. The imperturbable calm of the penetrating filmmaking of Citizenfour holds reservoirs of disappointment, anger and finally, wellsprings of hope.

11. Citizenfour, Laura Poitras. Edward Snowden’s loquacity in describing the responsibility of a governed citizenry, as well as the elemental passion he expresses for American ideals, stand in stark contrast to the grandstanding of onscreen politicos and spooks, and elevate what could be merely technical talk about “metadata in aggregate” and how billions of conversations could be (and are) siphoned into the data coffers of the government and its contractors each day to something approaching manifesto. The imperturbable calm of the penetrating filmmaking of Citizenfour holds reservoirs of disappointment, anger and finally, wellsprings of hope.

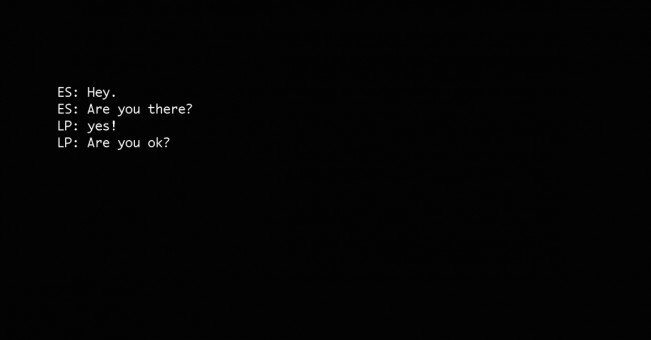

12. The Overnighters, Jesse Moss. Rich with hope and rife with despair, going in as many unexpected directions as life can offer. T. Griffin’s score is elemental to the melancholy of Moss’ mosaic of men in need: it’s as layered as the rest of the assured, compassionate, even brilliant filmmaking.

12. The Overnighters, Jesse Moss. Rich with hope and rife with despair, going in as many unexpected directions as life can offer. T. Griffin’s score is elemental to the melancholy of Moss’ mosaic of men in need: it’s as layered as the rest of the assured, compassionate, even brilliant filmmaking.

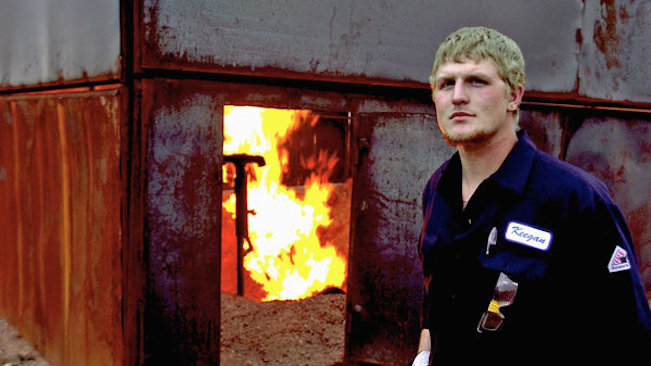

13. Only Lovers Left Alive, Jim Jarmusch. Superficially a vampire story—and one that portrays the soft rush of ingested blood like the hard rush of injected heroin—Only Lovers Left Alive is also a moving meditation on shifting roles in long-term relationships, on “zombie” culture outside the cluttered, cloistered lair, on the eternal promise and disappointment of youth. Keenly, Only Lovers demonstrates the importance of knowing who, in a couple, will be the one to dream and hold fast while the other might flag and despair. It’s also an impeccably furnished paean to cultivated taste in which its practitioners have had centuries to also develop impeccable self-awareness.

13. Only Lovers Left Alive, Jim Jarmusch. Superficially a vampire story—and one that portrays the soft rush of ingested blood like the hard rush of injected heroin—Only Lovers Left Alive is also a moving meditation on shifting roles in long-term relationships, on “zombie” culture outside the cluttered, cloistered lair, on the eternal promise and disappointment of youth. Keenly, Only Lovers demonstrates the importance of knowing who, in a couple, will be the one to dream and hold fast while the other might flag and despair. It’s also an impeccably furnished paean to cultivated taste in which its practitioners have had centuries to also develop impeccable self-awareness.

14. Force Majeure, Ruben Östlund. A ticklish mix of Billy Wilder (visual wit and verbal precision are deployed adroitly), Luis Buñuel (the amazing final scene) and Scandinavian modern exactness, Force Majeure thrills for its biting wit as well as its portrayal of how the smallest choice, the most seemingly minor gesture, can be as dramatically calamitous and emotionally revealing as pitched heights of drama.

14. Force Majeure, Ruben Östlund. A ticklish mix of Billy Wilder (visual wit and verbal precision are deployed adroitly), Luis Buñuel (the amazing final scene) and Scandinavian modern exactness, Force Majeure thrills for its biting wit as well as its portrayal of how the smallest choice, the most seemingly minor gesture, can be as dramatically calamitous and emotionally revealing as pitched heights of drama.

15. Mr. Turner, Mike Leigh. Leigh brings a longtime dream to supple fruition: a robust yet understated, unalloyed two-and-half-hour celebration of the boldly imagined, bracingly colored, late work of the great painter J.M.W. Turner, as well as his curmudgeonly disposition, captured by Timothy Spall in classic dudgeon.

15. Mr. Turner, Mike Leigh. Leigh brings a longtime dream to supple fruition: a robust yet understated, unalloyed two-and-half-hour celebration of the boldly imagined, bracingly colored, late work of the great painter J.M.W. Turner, as well as his curmudgeonly disposition, captured by Timothy Spall in classic dudgeon.

16. Life Itself, Steve James. Chicago’s own Steve James seems like an inspired choice to capture the competitive, complex years of Roger Ebert’s life. Working again with his longtime co-producers, Kartemquin Films, the director of Hoop Dreams and The Interrupters packs seventy years into a swift, swinging two hours, a dense, vivid impression of the Sun-Timesman’s will and destiny to be a newspaperman from the earliest age, but also the many overlapping eras of his eventful (and competitive) life. Editor-in-chief at college, appointed film critic almost by accident at a callow age, the drinking, the rivalry with Gene Siskel, Chaz, the loss of voice alongside the gain of a virtual pulpit, the ornery Midwestern strength in the face of debilitating pain in his final days. There are hundreds of stories to be told and, as has been amply pointed out, at Sundance and elsewhere, hundreds of people have them, their own Roger Ebert story from the late, great everyman’s simple, elemental curiosity. There’s a lot between the covers of Ebert’s fugue-cum-memoir that gives the film its title and some of its territory, but for a movie made in just over a year, it’s a compact feat of determination and legerdemain. Life Itself is a proper, not wholly reverent remembrance. The filmmakers have even provided a place of pride for the immortal line Roger wrote in his screenplay for Russ Meyer’s “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls”: “This is my happening and it freaks me out!”

16. Life Itself, Steve James. Chicago’s own Steve James seems like an inspired choice to capture the competitive, complex years of Roger Ebert’s life. Working again with his longtime co-producers, Kartemquin Films, the director of Hoop Dreams and The Interrupters packs seventy years into a swift, swinging two hours, a dense, vivid impression of the Sun-Timesman’s will and destiny to be a newspaperman from the earliest age, but also the many overlapping eras of his eventful (and competitive) life. Editor-in-chief at college, appointed film critic almost by accident at a callow age, the drinking, the rivalry with Gene Siskel, Chaz, the loss of voice alongside the gain of a virtual pulpit, the ornery Midwestern strength in the face of debilitating pain in his final days. There are hundreds of stories to be told and, as has been amply pointed out, at Sundance and elsewhere, hundreds of people have them, their own Roger Ebert story from the late, great everyman’s simple, elemental curiosity. There’s a lot between the covers of Ebert’s fugue-cum-memoir that gives the film its title and some of its territory, but for a movie made in just over a year, it’s a compact feat of determination and legerdemain. Life Itself is a proper, not wholly reverent remembrance. The filmmakers have even provided a place of pride for the immortal line Roger wrote in his screenplay for Russ Meyer’s “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls”: “This is my happening and it freaks me out!”

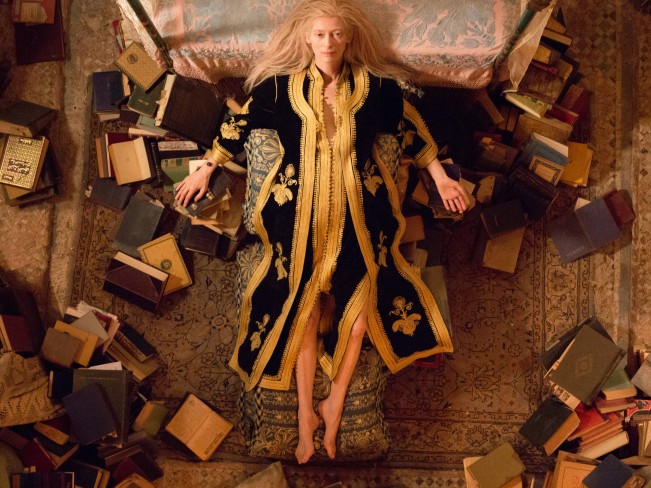

17. Inherent Vice, Paul Thomas Anderson. This one will take a few trips to fully figure. Anderson situates “Inherent Vice,” Thomas Pynchon’s 2009 fractured fairytale of private eyes, lingering love, the power of overlapping narcotics, and the death of the sixties in his birth year of 1970, to fractiously comic but almost militantly melancholy ends. In the novel, Pynchon describes that small moment when radical hopes and stoner joy had punched a hole in the sky as “this little parenthesis of light.” In Anderson’s adaptation, nearly as rife with cross-references and richly oddball dialogue as Pynchon’s prose—liberally invoked both spoken and in narration—comedy and tragedy align in the lovelorn figure of P.I. “Doc” Sportello, a doofus in a daze rendered with the most precise of physical acuity by Joaquin Phoenix in 1970s-era Neil Young drag, replete with a munificence of muttonchops.

17. Inherent Vice, Paul Thomas Anderson. This one will take a few trips to fully figure. Anderson situates “Inherent Vice,” Thomas Pynchon’s 2009 fractured fairytale of private eyes, lingering love, the power of overlapping narcotics, and the death of the sixties in his birth year of 1970, to fractiously comic but almost militantly melancholy ends. In the novel, Pynchon describes that small moment when radical hopes and stoner joy had punched a hole in the sky as “this little parenthesis of light.” In Anderson’s adaptation, nearly as rife with cross-references and richly oddball dialogue as Pynchon’s prose—liberally invoked both spoken and in narration—comedy and tragedy align in the lovelorn figure of P.I. “Doc” Sportello, a doofus in a daze rendered with the most precise of physical acuity by Joaquin Phoenix in 1970s-era Neil Young drag, replete with a munificence of muttonchops.

18. Two Days, One Night, Jean-Pierre Dardenne, Luc Dardenne. Capital aligns worker against worker and a depressed woman must seek the sufferance of her co-workers if she is to keep her job. For their first collaboration with a star actor, the Dardennes have exceptional fortune with the harried but haunting features of Marion Cotillard.

18. Two Days, One Night, Jean-Pierre Dardenne, Luc Dardenne. Capital aligns worker against worker and a depressed woman must seek the sufferance of her co-workers if she is to keep her job. For their first collaboration with a star actor, the Dardennes have exceptional fortune with the harried but haunting features of Marion Cotillard.

19. Selma, Ava DuVernay. Understated yet righteously furious, with moments of bold visual kineticism, Selma kaleidoscopically emphasizes the importance of the group in political action as much as the charismatic leader. (The film’s called Selma, not “King.”) Plus: Voting Rights. Didn’t these marches insure them for the American century to come?

19. Selma, Ava DuVernay. Understated yet righteously furious, with moments of bold visual kineticism, Selma kaleidoscopically emphasizes the importance of the group in political action as much as the charismatic leader. (The film’s called Selma, not “King.”) Plus: Voting Rights. Didn’t these marches insure them for the American century to come?

20. The Disappearance Of Eleanor Rigby: Her/Him, Ned Benson. The delicately astonishing The Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby relates two subtly, tellingly different sides of the aftermath of the sudden detonation of the lives of a married couple with a child, the first from the dreamily subdued perspective of a woman named Eleanor Rigby (Jessica Chastain), and subtitled “Her,” and the second from the more volatile perspective of her estranged husband, Conor (James McAvoy). When the narrative shifts to Conor’s perspective, scenes that were played between Chastain and McAvoy’s characters repeat, but with subtle variations in dialogue and dramatic emphasis. The separate events in their lives, when they are apart, are equally telling: the bruised hush of “Her” rises to confounded masculine disarray as we discover further eddies of grieving in the lives around “Her.” The essential elegance of this structure is how we, as viewers, have to reconstruct our memory of prior events, if only an hour, hour-and-a-half before, the way the characters, her and him, try to reconstruct tragic events of only a few months earlier.

20. The Disappearance Of Eleanor Rigby: Her/Him, Ned Benson. The delicately astonishing The Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby relates two subtly, tellingly different sides of the aftermath of the sudden detonation of the lives of a married couple with a child, the first from the dreamily subdued perspective of a woman named Eleanor Rigby (Jessica Chastain), and subtitled “Her,” and the second from the more volatile perspective of her estranged husband, Conor (James McAvoy). When the narrative shifts to Conor’s perspective, scenes that were played between Chastain and McAvoy’s characters repeat, but with subtle variations in dialogue and dramatic emphasis. The separate events in their lives, when they are apart, are equally telling: the bruised hush of “Her” rises to confounded masculine disarray as we discover further eddies of grieving in the lives around “Her.” The essential elegance of this structure is how we, as viewers, have to reconstruct our memory of prior events, if only an hour, hour-and-a-half before, the way the characters, her and him, try to reconstruct tragic events of only a few months earlier.

21. La jalousie, Philipe Garrel. Later, his mistress says, “I can handle being broke, but not poor,” and later still, she surprises him with the display of a large, bright apartment being restored. “He must love you to give you this,” he says of the other man. “This is nuts. You don’t even deny it!” She’s Gallic savoir-faire through and through. “We’re here to have as full a life as possible.” A man, he’s still elementally a boy: “Imagining you with another guy hurts.” “Don’t imagine it,” she says in her raspy voice, notably off-camera, “Enjoy it when we’re together. Forget it when we’re not. When I’m with you, I want to be.” He stares, struck. “Why are you trying to hurt me? Why do you want to hurt me?” “I don’t want to hurt you,” she says, “I thought you’d be happy.” The floorboards of the unfinished apartment creak. That sound is like the roar of an ice floe breaking off, small, even mouse-tiny, yet it’s like the calving of a glacier. That split-second is cinema. That split-second is the rending of two hearts. Plus, the never-mastered lesson, pride kills. Or pride, at the very least, mixed with a toxic cocktail of self-pity, will make you want to harm yourself.

21. La jalousie, Philipe Garrel. Later, his mistress says, “I can handle being broke, but not poor,” and later still, she surprises him with the display of a large, bright apartment being restored. “He must love you to give you this,” he says of the other man. “This is nuts. You don’t even deny it!” She’s Gallic savoir-faire through and through. “We’re here to have as full a life as possible.” A man, he’s still elementally a boy: “Imagining you with another guy hurts.” “Don’t imagine it,” she says in her raspy voice, notably off-camera, “Enjoy it when we’re together. Forget it when we’re not. When I’m with you, I want to be.” He stares, struck. “Why are you trying to hurt me? Why do you want to hurt me?” “I don’t want to hurt you,” she says, “I thought you’d be happy.” The floorboards of the unfinished apartment creak. That sound is like the roar of an ice floe breaking off, small, even mouse-tiny, yet it’s like the calving of a glacier. That split-second is cinema. That split-second is the rending of two hearts. Plus, the never-mastered lesson, pride kills. Or pride, at the very least, mixed with a toxic cocktail of self-pity, will make you want to harm yourself.

22. The Great Invisible, Margaret Brown. Sober, beautiful, infuriating and utterly essential.

22. The Great Invisible, Margaret Brown. Sober, beautiful, infuriating and utterly essential.

23. Locke, Stephen Knight. As voices punch at him in succession and repetition, perspective blurs and light sources eddy red, white, blue, yellow, guttering like phosphorescent tapers, streaks and flurries of headlamps, tail lights, red and white light elongating from facing directions. Antiquated Panavision lenses add to the bloom and anamorphic splay of light sources in every shot. It’s light as inchoate emotion, light as insensate commentary, a sure, persistent mood. Light plays over the BMW, kaleidoscopic glimmers, a neon tapestry of urban night world that scans across his features as he traverses the motorway, the play of light off other vehicles silently sizzling, relentlessly simmering surfaces infecting his calm. Cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos’ fondness for textures, seen in films like Enduring Love, nests in Locke’s nubby fisherman’s-style sweater, one element in the confines of the car that turn the space cannily domestic. As Locke grows more distressed, that look provides a vital visual-emotional corollary to Michael Mann’s slashing action painting of ineffectual masculinity’s pageantry. But Locke is more than mere sensation. Its great beauty first swims in light, then lies in language, and finally rests in the beating heart of its protagonist. Locke’s dialogue rises to the punchy, pounding, yet ethereal reaches of the spoken beauty of the likes of Abraham Polonsky’s Body & Soul and Force Of Evil. Why does Locke do what he does? A rare, soulful passage amid his patient verbal negotiation with life itself: “You do it for the piece of sky we are stealing with our building. You do it for the air that will be displaced. And most of all you do it for the fucking concrete, because it is delicate as blood.” And what danger does Locke live with? “You make one mistake, one little fucking mistake, and the whole world comes crashing down around you.” That is the film, that is his life.

23. Locke, Stephen Knight. As voices punch at him in succession and repetition, perspective blurs and light sources eddy red, white, blue, yellow, guttering like phosphorescent tapers, streaks and flurries of headlamps, tail lights, red and white light elongating from facing directions. Antiquated Panavision lenses add to the bloom and anamorphic splay of light sources in every shot. It’s light as inchoate emotion, light as insensate commentary, a sure, persistent mood. Light plays over the BMW, kaleidoscopic glimmers, a neon tapestry of urban night world that scans across his features as he traverses the motorway, the play of light off other vehicles silently sizzling, relentlessly simmering surfaces infecting his calm. Cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos’ fondness for textures, seen in films like Enduring Love, nests in Locke’s nubby fisherman’s-style sweater, one element in the confines of the car that turn the space cannily domestic. As Locke grows more distressed, that look provides a vital visual-emotional corollary to Michael Mann’s slashing action painting of ineffectual masculinity’s pageantry. But Locke is more than mere sensation. Its great beauty first swims in light, then lies in language, and finally rests in the beating heart of its protagonist. Locke’s dialogue rises to the punchy, pounding, yet ethereal reaches of the spoken beauty of the likes of Abraham Polonsky’s Body & Soul and Force Of Evil. Why does Locke do what he does? A rare, soulful passage amid his patient verbal negotiation with life itself: “You do it for the piece of sky we are stealing with our building. You do it for the air that will be displaced. And most of all you do it for the fucking concrete, because it is delicate as blood.” And what danger does Locke live with? “You make one mistake, one little fucking mistake, and the whole world comes crashing down around you.” That is the film, that is his life.

24. The LEGO Movie, Phil Lord, Christopher Miller. I have seen bits and pieces of this since its video release as if I were a 10-year-old boy, and even then, I would have believed Everything Is Awesome.

24. The LEGO Movie, Phil Lord, Christopher Miller. I have seen bits and pieces of this since its video release as if I were a 10-year-old boy, and even then, I would have believed Everything Is Awesome.

25. The Babadook, Jennifer Kent. “A bad book,” indeed. For all its primal borrowing from other movies, The Babadook is first and foremost a Jennifer Kent film, and it’s great. She’s burned her influences, and the result is indelible, and toxic and scalding and scarifying and terrific to the touch.

25. The Babadook, Jennifer Kent. “A bad book,” indeed. For all its primal borrowing from other movies, The Babadook is first and foremost a Jennifer Kent film, and it’s great. She’s burned her influences, and the result is indelible, and toxic and scalding and scarifying and terrific to the touch.

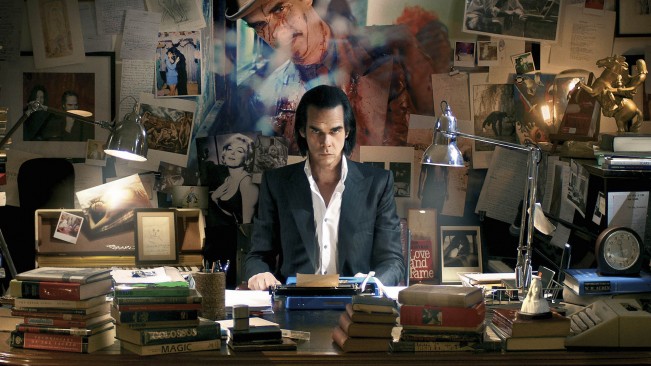

26. 20,000 Days On Earth, Iain Forsyth, Jane Pollard. Forsyth and Pollard’s directorial debut is stellar, a rich, luxuriant, calibrated auto-portrait of Nick Cave, not quite fact, not quite fiction, told as if it were taking place in a single day, in words, music, a first-time psychotherapy session, and personal hallucinations with former musical partners Kylie Minogue and Blixa Bargeld in his car as he drives alongside the sea near his Brighton, England home. It sounds like so much attenuated tosh, but this bold, unique gem is bright, funny, brooding, hopeful, momentarily visionary, a wounded beauty exploring the creative process in a fresh and oft-brilliant fashion. Plus! As you’d expect, Nick Cave sings, and with at least one children’s choir to boot.

26. 20,000 Days On Earth, Iain Forsyth, Jane Pollard. Forsyth and Pollard’s directorial debut is stellar, a rich, luxuriant, calibrated auto-portrait of Nick Cave, not quite fact, not quite fiction, told as if it were taking place in a single day, in words, music, a first-time psychotherapy session, and personal hallucinations with former musical partners Kylie Minogue and Blixa Bargeld in his car as he drives alongside the sea near his Brighton, England home. It sounds like so much attenuated tosh, but this bold, unique gem is bright, funny, brooding, hopeful, momentarily visionary, a wounded beauty exploring the creative process in a fresh and oft-brilliant fashion. Plus! As you’d expect, Nick Cave sings, and with at least one children’s choir to boot.

27. Listen Up Philip, Alex Ross Perry. While Schwartzman and Pryce present their men at their worst, Moss finds a wounded but not fragile grace in her scenes, including near-transcendent bits of behavior near the end. While the tightly composed, handheld camerawork has an in-your-face intensity that should be off-putting, the pacing has drive and punch that compensates. Perry cites Woody Allen’s Husbands and Wives as inspiration for the superficially haphazard look and feel. (The editing is by estimable filmmaker-critic Robert Greene, whose documentaries include Fake It So Real and Actress.)

27. Listen Up Philip, Alex Ross Perry. While Schwartzman and Pryce present their men at their worst, Moss finds a wounded but not fragile grace in her scenes, including near-transcendent bits of behavior near the end. While the tightly composed, handheld camerawork has an in-your-face intensity that should be off-putting, the pacing has drive and punch that compensates. Perry cites Woody Allen’s Husbands and Wives as inspiration for the superficially haphazard look and feel. (The editing is by estimable filmmaker-critic Robert Greene, whose documentaries include Fake It So Real and Actress.)

28. A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night, Ana Lily Amirpour. A confident widescreen, black-and-white Farsi-language all-American debut, a bracing post-punk blend of vampire iconography, the spaghetti western, Kaurismäki-like sorrowfulness, Jarmusch-worthy equipoise, shot in Bakersfield, California, which passes for the nocturnal reaches “Bad City,” Iran. Amirpour’s politically suggestive feature debut is ripe with eye-widening joy from its first frames, its pacing alternately languorous and coiled, the graphic-novel-like imagery emerging and evolving with surrealist stealth.

28. A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night, Ana Lily Amirpour. A confident widescreen, black-and-white Farsi-language all-American debut, a bracing post-punk blend of vampire iconography, the spaghetti western, Kaurismäki-like sorrowfulness, Jarmusch-worthy equipoise, shot in Bakersfield, California, which passes for the nocturnal reaches “Bad City,” Iran. Amirpour’s politically suggestive feature debut is ripe with eye-widening joy from its first frames, its pacing alternately languorous and coiled, the graphic-novel-like imagery emerging and evolving with surrealist stealth.

29. The Rover, David Michôd. The story of The Rover is simple: it’s no tract. “History” is happening elsewhere. Eric (Guy Pearce), a man who alternates between a thousand-yard stare and fire in his eyes, sunburnt and grizzled, is gripped by unexplained pain. Three men steal his car. He wants his car back. That’s what drives him, that’s what he tells everyone he meets. He wants his car back. He’s like Lee Marvin’s Point Blank character, Walker, a man who only wants what he’s earned. “I want my money” was his refrain; Pearce’s “I want my car.” (His monocular quest also evokes Monte Hellman’s Cockfighter” in which Warren Oates’ character refuses to speak until the next time his chicken wins.) The three car thieves were on the run from a botched robbery, where one man’s younger brother, Rey (Robert Pattinson), was left for dead. As in the many Westerns The Rover resembles, new bonds form. Families are shaken, then shaped by tragedy. The robustly twitchy Pattinson and Pearce make combustible alliance in search of Rey’s brother. At moments, under burnished yet offhanded light, The Rover is literary machismo of a high order. And at others? We’re watching Michelangelo Antonioni’s Mad Max. (This is not a bad thing.) Michôd and cinematographer Natasha Braier emphasize masculine determination and ineffectuality by fixing repeatedly on the roll of men’s shoulders, face turned to the horizon, spiritual burden expressed in a hitch of step and pitch of the male frame.

29. The Rover, David Michôd. The story of The Rover is simple: it’s no tract. “History” is happening elsewhere. Eric (Guy Pearce), a man who alternates between a thousand-yard stare and fire in his eyes, sunburnt and grizzled, is gripped by unexplained pain. Three men steal his car. He wants his car back. That’s what drives him, that’s what he tells everyone he meets. He wants his car back. He’s like Lee Marvin’s Point Blank character, Walker, a man who only wants what he’s earned. “I want my money” was his refrain; Pearce’s “I want my car.” (His monocular quest also evokes Monte Hellman’s Cockfighter” in which Warren Oates’ character refuses to speak until the next time his chicken wins.) The three car thieves were on the run from a botched robbery, where one man’s younger brother, Rey (Robert Pattinson), was left for dead. As in the many Westerns The Rover resembles, new bonds form. Families are shaken, then shaped by tragedy. The robustly twitchy Pattinson and Pearce make combustible alliance in search of Rey’s brother. At moments, under burnished yet offhanded light, The Rover is literary machismo of a high order. And at others? We’re watching Michelangelo Antonioni’s Mad Max. (This is not a bad thing.) Michôd and cinematographer Natasha Braier emphasize masculine determination and ineffectuality by fixing repeatedly on the roll of men’s shoulders, face turned to the horizon, spiritual burden expressed in a hitch of step and pitch of the male frame.

30. Obvious Child, Gillian Robespierre. Robespierre’s canny, taut debut, a distinctly contemporary comedy, is rich in people talk and how some people swear and how modern audiences laugh, shocked, with gratitude. And lead actress Jenny Slate? Here comes a great comedy star in a smart, conversational, bluntly funny, certainly subversive romcom.

30. Obvious Child, Gillian Robespierre. Robespierre’s canny, taut debut, a distinctly contemporary comedy, is rich in people talk and how some people swear and how modern audiences laugh, shocked, with gratitude. And lead actress Jenny Slate? Here comes a great comedy star in a smart, conversational, bluntly funny, certainly subversive romcom.

31. Edge Of Tomorrow, Doug Liman. Repeated fractions of action setpieces, with key variations in choreography, maximize the substantial production value, but the editing of the intricate battle scenes must have been a mathematical affliction. There are splendidly weird details throughout, rich with resourceful zip, including plainly lunatic dialogue that sounds the plot but also rings as terse spoken poesy, as a matter of life and breath: “I do this to avoid doing that”; “Never asked, don’t care”; “Come find me when you wake up”; “The Omega has the ability to control time”; “This is a perfectly formed world-conquering organism!” and “I watched him die three-hundred times.” Plus, the verity of “I haven’t lived this day. I don’t know what’s going to happen.”

31. Edge Of Tomorrow, Doug Liman. Repeated fractions of action setpieces, with key variations in choreography, maximize the substantial production value, but the editing of the intricate battle scenes must have been a mathematical affliction. There are splendidly weird details throughout, rich with resourceful zip, including plainly lunatic dialogue that sounds the plot but also rings as terse spoken poesy, as a matter of life and breath: “I do this to avoid doing that”; “Never asked, don’t care”; “Come find me when you wake up”; “The Omega has the ability to control time”; “This is a perfectly formed world-conquering organism!” and “I watched him die three-hundred times.” Plus, the verity of “I haven’t lived this day. I don’t know what’s going to happen.”

32. Maps To The Stars, David Cronenberg. The fluent severity of Cronenberg’s frames (shot, as customary, by Peter Suschitzky) matches elegantly to the linguistically bedizened, behaviorally fetid prose of his good friend, novelist Bruce Wagner. It’s not the Hollywood satire some have taken it for, but a four-hankie dry weep for the soul of a society where sensation high and low cannot match urge and habit. (Incest; pistols; endangered pets; fire that burns but does not yet physically consume; Klonopin, Romeo + Juliet; fame! O fame; “deathless American icons,” self-delusion; the lurid as quotidian.)

32. Maps To The Stars, David Cronenberg. The fluent severity of Cronenberg’s frames (shot, as customary, by Peter Suschitzky) matches elegantly to the linguistically bedizened, behaviorally fetid prose of his good friend, novelist Bruce Wagner. It’s not the Hollywood satire some have taken it for, but a four-hankie dry weep for the soul of a society where sensation high and low cannot match urge and habit. (Incest; pistols; endangered pets; fire that burns but does not yet physically consume; Klonopin, Romeo + Juliet; fame! O fame; “deathless American icons,” self-delusion; the lurid as quotidian.)

33. Whiplash, Damien Chazelle. A musical, an accomplished short story, like a boxing film, a horror show, a forceful suspense thriller, a bold and bracing memento mori of the will to greatness, male ego, control, arrogance, talent, douchiness, selfishness, desire, hope, transcendence.

33. Whiplash, Damien Chazelle. A musical, an accomplished short story, like a boxing film, a horror show, a forceful suspense thriller, a bold and bracing memento mori of the will to greatness, male ego, control, arrogance, talent, douchiness, selfishness, desire, hope, transcendence.

34. Snowpiercer, Bong Joon-ho. The oppressed of the farthest reaches of the tail of the train are prepared to revolt, to make their way to the front of the train, to…? They know no other world, not even sunlight glinted off the expanses of barren snow and frozen cities they circuit past. Cinematic intelligence and Bong’s unwavering class-consciousness offer up a fierce fable for our end times.

34. Snowpiercer, Bong Joon-ho. The oppressed of the farthest reaches of the tail of the train are prepared to revolt, to make their way to the front of the train, to…? They know no other world, not even sunlight glinted off the expanses of barren snow and frozen cities they circuit past. Cinematic intelligence and Bong’s unwavering class-consciousness offer up a fierce fable for our end times.

35. Stranger By The Lake, Alain Guiraudie. Classically constructed, as rigid in its construction of suspense as any recent thriller, Stranger by the Lake is a masterful work, uncluttered yet lush, formally regimented, yet always surprising. (Call it full-frontal Hitchcock.) It also takes its location, its construction of sexuality, as commonplace. Guiraudie’s movie is assuredly part and parcel of queer cinema, but also of the cinema of the quotidian, of the everyday.

35. Stranger By The Lake, Alain Guiraudie. Classically constructed, as rigid in its construction of suspense as any recent thriller, Stranger by the Lake is a masterful work, uncluttered yet lush, formally regimented, yet always surprising. (Call it full-frontal Hitchcock.) It also takes its location, its construction of sexuality, as commonplace. Guiraudie’s movie is assuredly part and parcel of queer cinema, but also of the cinema of the quotidian, of the everyday.

36. The Duke Of Burgundy, Peter Strickland. A post-Tears Of Petra Von Kant delineation of the psychology of the dominant-submissive relationship told as a dusty, cloistered, hothouse relationship between two women who study butterflies and each other. With sound, image, implication, and obstinate psychological observation, Strickland is a talent that can only grow more venturesome. When Radley Metzger met Joseph Losey met… Strickland has the gift of seeming sui generis even when intellectually aware of a thousand influences in his mind and quiver.

36. The Duke Of Burgundy, Peter Strickland. A post-Tears Of Petra Von Kant delineation of the psychology of the dominant-submissive relationship told as a dusty, cloistered, hothouse relationship between two women who study butterflies and each other. With sound, image, implication, and obstinate psychological observation, Strickland is a talent that can only grow more venturesome. When Radley Metzger met Joseph Losey met… Strickland has the gift of seeming sui generis even when intellectually aware of a thousand influences in his mind and quiver.

37. Leviathan, Andrey Zvyagintsev. Tempers simmer, imbibe, combust, with righteously apocalyptic fury. Did I mention that it might also be the year’s most accomplished black comedy? A gurgling in the darkness that leads only to truest blackness? Leviathan is one lovingly tooled blunderbuss.

37. Leviathan, Andrey Zvyagintsev. Tempers simmer, imbibe, combust, with righteously apocalyptic fury. Did I mention that it might also be the year’s most accomplished black comedy? A gurgling in the darkness that leads only to truest blackness? Leviathan is one lovingly tooled blunderbuss.

38. Blue Ruin, Jeremy Saulnier. In Saulnier’s work as a cinematographer only, like Matt Porterfield’s I Used To Be Darker, nuanced lighting is used to gently drape quiet drama, whereas in Blue Ruin, a revenge thriller, the work is behaviorally nuanced, vitally designed, framed and cut, blue-to-bruise blue-to-beyond-bruise and even at its leanest moments, rocking with brooding unease. Dwight goes about the particulars of his day, and no matter how quotidian, they sing with the potential of malice. The suspense comes from how soon, how exponentially, he might further fuck things up. Blue Ruin does not disappoint in that regard, either. Saulnier ditches the patter and deals out the splatter.

38. Blue Ruin, Jeremy Saulnier. In Saulnier’s work as a cinematographer only, like Matt Porterfield’s I Used To Be Darker, nuanced lighting is used to gently drape quiet drama, whereas in Blue Ruin, a revenge thriller, the work is behaviorally nuanced, vitally designed, framed and cut, blue-to-bruise blue-to-beyond-bruise and even at its leanest moments, rocking with brooding unease. Dwight goes about the particulars of his day, and no matter how quotidian, they sing with the potential of malice. The suspense comes from how soon, how exponentially, he might further fuck things up. Blue Ruin does not disappoint in that regard, either. Saulnier ditches the patter and deals out the splatter.

39. L For Leisure, Whitney Horn, Lev Kalman. The soul of drifting. The drifting of soul. Genteel music taking you for granted.

39. L For Leisure, Whitney Horn, Lev Kalman. The soul of drifting. The drifting of soul. Genteel music taking you for granted.

.

.

40. Interstellar, Christopher Nolan. Not for my experience of a single viewing of the film in IMAX, but for two pieces of writing that Nolan inspired. Aaron Stewart-Ahn: “Let’s make a giant leap. I believe the most profound inversion is the very identity of ‘they’: the offscreen, mysterious, never seen transdimensional observers that influence events in the story. Alluded to as beings with access to an atemporal, fifth dimensionally liberated view of time, creators of a wormhole, with mastery over space, time and gravity, by the film’s end we learn that ‘they’ is ‘us'” evolutionarily and technologically advanced humans far into the future. From Hideaki Anno’s ‘End of Evangelion’: footage of viewers watching the movie for the first time were intercut into the movie. I theorize that Interstellar actually makes you one of those beings. It is us, literally. The deus ex machina in the story is you, the observer watching the movie, and science tells us that to watch something is to change it. Let me explain…” And Bilge Ebiri: “Interstellar has never really been about science; any science in it has always been at the service of Nolan’s more poetic ambitions. And here, the film abandons any pretense to physics and enters a strange, wonderful netherworld between dreamy metaphor and literal-minded fantasy… Memories and moments–repeated, obsessed over–have always held a privileged place in Nolan’s filmography. And so, not unlike Cobb’s dreams of the room in which his wife killed herself in Inception, Coop finds himself back in one of Nolan’s memory chambers. This tesseract here at the end of Interstellar, supposedly created by humans who have mastered five dimensions, is sort of like one of Nolan’s movies, a place of hazy emotions and hard angles; the surfaces may be tough, but at heart, the director’s always been a softie. (That’s why I’ve never bought the criticism that his films are ‘nihilistic”; if anything, they’re unabashedly earnest.)”

And more, alphabetical:

Art and Craft

Big Hero 6

Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance)

Captain America: The Winter Soldier

Cheap Thrills

Closed Curtain

Coherence

Enemy

Farewell to Language

The Fault in Our Stars

Finding Vivian Maier

Guardians of the Galaxy

The Guest

Jeune & Jolie

Joe

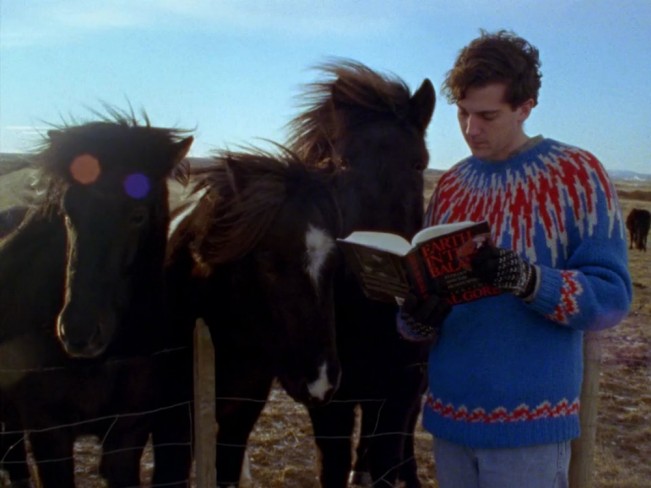

Land Ho!

Last Days Of Vietnam

The Last Of The Unjust

A Most Violent Year

National Gallery

Nightcrawler

Nymphomaniac Vol. I

Palo Alto

Starred Up

Top Five

Tracks

Under The Skin

The Unknown Known

Wild

Among many, many others to catch up with in 2015

Beyond the Lights; The Grim Sleeper; John Wick; The Life Of Riley; Lucy; Maidan; Memphis; Mommy; Norte, The End of History; The Skeleton Twins; Still Alice; The Story Of My Death; The Tale of the Princess Kaguya; Wild Tales

While I’m sure much of this piece is well-written, I wanted to commend you on the poetic economy employed in your intelligent and thoughtful summary of your feelings toward ‘Inherent Vice’.

Thanks… There’s a lot beneath the paving stones.