Movie City Indie Archive for December, 2013

Best Of 2013: Features

The twenty-five films that follow all possess a “wow” factor. There’s a wealth of disparate, eye-widening goodness. Movies, large and small alike, are going interesting places. Then, alphabetically, thirty-three more samples of 2013’s bounty. Some I saw during on the regular reviewing beat—there are links to most films from reviews at MCN and Newcity—and others at Sundance and fantastic smaller festivals like True/False, the Thessaloniki International Film Festival, the Sarasota Film Festival and EbertFest. (The first iteration of 2013 list-making: my indieWIRE poll ballot. Second iteration: Newcity’s Top 5 Of Everything: Film.)

1. Inside Llewyn Davis, Joel Coen, Ethan Coen. Zen Coen.

1. Inside Llewyn Davis, Joel Coen, Ethan Coen. Zen Coen.

2. Her, Spike Jonze. In a softly lit, given-to-orange-red Los Angeles, Theodore (muted, damped Joaquin Phoenix) procrastinates on finalizing his divorce while thinking of what went wrong with his wife, while having a warm, platonic friendship with his neighbor, a married documentary-maker and programmer. His sentiments shift when he buys an operating system for his computer, an intuitive entity that listens to you, that understands you, which dubs itself Samantha and has a chipper, flirtatious, intimate, slightly husky voice: Scarlett Johansson. A.I.-yi-yi: she’s got the emotional intelligence of a lover and a mother. The conceit sounds awful from outside, but inside Her, it’s supertragicmagicdelicious: Spike Jonze and his collaboroators really, really make it work.

2. Her, Spike Jonze. In a softly lit, given-to-orange-red Los Angeles, Theodore (muted, damped Joaquin Phoenix) procrastinates on finalizing his divorce while thinking of what went wrong with his wife, while having a warm, platonic friendship with his neighbor, a married documentary-maker and programmer. His sentiments shift when he buys an operating system for his computer, an intuitive entity that listens to you, that understands you, which dubs itself Samantha and has a chipper, flirtatious, intimate, slightly husky voice: Scarlett Johansson. A.I.-yi-yi: she’s got the emotional intelligence of a lover and a mother. The conceit sounds awful from outside, but inside Her, it’s supertragicmagicdelicious: Spike Jonze and his collaboroators really, really make it work.

3. Before Midnight, Richard Linklater. This very literary accomplishment, as in all of Linklater’s best work, is unassuming, coming through action, behavior, character. And what characters! Their persistent aggravation with each other indicates so much time spent together, so much intimacy and so little self-knowledge. (They misunderstand each other so well.) “We’re not fighting, we’re negotiating,” she says, and surely not for the last time. They stand near the sea, timeless beauty, endless vista, and an iPhone text message goes plunk. Antiquity, meet modernity: so much in the simplest sound.

3. Before Midnight, Richard Linklater. This very literary accomplishment, as in all of Linklater’s best work, is unassuming, coming through action, behavior, character. And what characters! Their persistent aggravation with each other indicates so much time spent together, so much intimacy and so little self-knowledge. (They misunderstand each other so well.) “We’re not fighting, we’re negotiating,” she says, and surely not for the last time. They stand near the sea, timeless beauty, endless vista, and an iPhone text message goes plunk. Antiquity, meet modernity: so much in the simplest sound.

4. Gravity, Alfonso Cuarón. Ninety minutes plus ninety million, a hundred, whatever they spent: this is a taut thriller built for audiences but also one of the most expensive experimental movies ever made.

4. Gravity, Alfonso Cuarón. Ninety minutes plus ninety million, a hundred, whatever they spent: this is a taut thriller built for audiences but also one of the most expensive experimental movies ever made.

5. Something In The Air, Olivier Assayas. Dreamily paced, serenely elliptical and seldom less than beautiful, Something In The Air looks back at Assayas’ own coming to awareness, but also engages in a serious conversation with the late work of French master Robert Bresson, including his L’argent, Four Nights of a Dreamer and especially, The Devil, Probably. There is an implacable, concrete beauty to those films, where objects and colors and young faces, especially young male faces, are presented as mute forces of manmade nature. (The ending of this film, however, impresses a female face onto the protagonist and the film watcher alike: a fantastic, phosphorescent image in a film about a film that loses its boundaries and becomes the film itself, pointing Gilles emphatically toward his vocation.)

5. Something In The Air, Olivier Assayas. Dreamily paced, serenely elliptical and seldom less than beautiful, Something In The Air looks back at Assayas’ own coming to awareness, but also engages in a serious conversation with the late work of French master Robert Bresson, including his L’argent, Four Nights of a Dreamer and especially, The Devil, Probably. There is an implacable, concrete beauty to those films, where objects and colors and young faces, especially young male faces, are presented as mute forces of manmade nature. (The ending of this film, however, impresses a female face onto the protagonist and the film watcher alike: a fantastic, phosphorescent image in a film about a film that loses its boundaries and becomes the film itself, pointing Gilles emphatically toward his vocation.)

6. A Touch Of Sin, Jia Zhangke. I can’t imagine a comparable American movie, militating passionately, lyrically over on the economic inequities of American life. It just isn’t done.

6. A Touch Of Sin, Jia Zhangke. I can’t imagine a comparable American movie, militating passionately, lyrically over on the economic inequities of American life. It just isn’t done.

7. The Grandmaster, Wong Kar-wai. Everything that seems truncated or abrupt in the American cut is explained, lengthened and deepened in the Chinese original. That version is a masterpiece of melancholy—Dr. Zhivago meets kung fu, as Wong himself describes it—while the American Grandmaster is a beautiful selection of setpieces that comes to a wholly different ending than Wong’s original cut. To be fair, Wong defends this version as his own, and most of his films have a range of international versions. But the 130-minute edition? It is to swoon. Even the buttons on a fine coat are given the emphasis of the whoosh of a blade, the crack of a bone or the scrape and grind and rush of a locomotive. Nothing is relative: all is memory. A dream.

7. The Grandmaster, Wong Kar-wai. Everything that seems truncated or abrupt in the American cut is explained, lengthened and deepened in the Chinese original. That version is a masterpiece of melancholy—Dr. Zhivago meets kung fu, as Wong himself describes it—while the American Grandmaster is a beautiful selection of setpieces that comes to a wholly different ending than Wong’s original cut. To be fair, Wong defends this version as his own, and most of his films have a range of international versions. But the 130-minute edition? It is to swoon. Even the buttons on a fine coat are given the emphasis of the whoosh of a blade, the crack of a bone or the scrape and grind and rush of a locomotive. Nothing is relative: all is memory. A dream.

8. Bastards, Claire Denis. Calculation always cuts both ways: against the victim and the avenging. Elliptical, as one expects of Denis, but also implacable in the forces that drive the cold passions of its hurt adults. Plus: digital wreaks marvelous dark in the hands of Denis and Agnès Godard.

8. Bastards, Claire Denis. Calculation always cuts both ways: against the victim and the avenging. Elliptical, as one expects of Denis, but also implacable in the forces that drive the cold passions of its hurt adults. Plus: digital wreaks marvelous dark in the hands of Denis and Agnès Godard.

9. Drug War, Johnnie To. It’s a joy to see such assured, efficient professionalism in latter-day action filmmaking, such dynamic alacrity in each and every visual element of the storytelling. And of course, the story, co-written with his customary collaborator, Wai Ka-Fai, of a meth cartel deep inside China that may be brought down over the course of seventy-two hours in a sting run by a detective and a turncoat criminal is filled with turns and burns and ooh-and-ah-worthy details and policier-style legerdemain. A key setpiece, set in daylight in early morning in the middle of a yet-to-be-populated industrial nowhere, accompanied by sulfurous fog that rolls in to the crack of gunfire from dozens of officers and criminals, is a blunt vision of the farther reaches of modern-day China. It’s also a tableau of hell that grows, compounding in a way that even a visionary filmmaker like Elem Klimov might appreciate. What the hell: Drug War is a taut, minor masterpiece. It felt like watching early Walter Hill for the first time—The Driver, Southern Comfort—and that is a very good feeling indeed. The cast is a joy to watch in motion, and especially, in strategic repose.

9. Drug War, Johnnie To. It’s a joy to see such assured, efficient professionalism in latter-day action filmmaking, such dynamic alacrity in each and every visual element of the storytelling. And of course, the story, co-written with his customary collaborator, Wai Ka-Fai, of a meth cartel deep inside China that may be brought down over the course of seventy-two hours in a sting run by a detective and a turncoat criminal is filled with turns and burns and ooh-and-ah-worthy details and policier-style legerdemain. A key setpiece, set in daylight in early morning in the middle of a yet-to-be-populated industrial nowhere, accompanied by sulfurous fog that rolls in to the crack of gunfire from dozens of officers and criminals, is a blunt vision of the farther reaches of modern-day China. It’s also a tableau of hell that grows, compounding in a way that even a visionary filmmaker like Elem Klimov might appreciate. What the hell: Drug War is a taut, minor masterpiece. It felt like watching early Walter Hill for the first time—The Driver, Southern Comfort—and that is a very good feeling indeed. The cast is a joy to watch in motion, and especially, in strategic repose.

10. Computer Chess, Andrew Bujalski. Computer Chess‘ deep-ecology tech comedy is completely under control, but never sacrifices its innate, lovely weirdness. Even the furnishings echo down the years, and not always to nostalgic joy: dinky digital watches, overhead projectors, brand names like Commodore and Zenith, the hard, plastic, hollow report of ancient keyboards clacking, worn and witnessed lumpish lads in Sansabelts, many with suspect mustaches. The men onscreen aren’t just “nerds” from a safe distance, historically, esthetically, they’re a dozen kind of so-male duffers and bluffers and mopers and dopers. They’re clever but not wise. The loopy existential comedy of Computer Chess reaches a blissful climax that only the film’s ugly, longhaired mash-faced stoner of a cat that wanders the motel’s creepy corridors could have predicted. By the end, it seems not only to have swallowed its own tail but also to have invented itself whole with but a C: prompt and a blinking cursor.

10. Computer Chess, Andrew Bujalski. Computer Chess‘ deep-ecology tech comedy is completely under control, but never sacrifices its innate, lovely weirdness. Even the furnishings echo down the years, and not always to nostalgic joy: dinky digital watches, overhead projectors, brand names like Commodore and Zenith, the hard, plastic, hollow report of ancient keyboards clacking, worn and witnessed lumpish lads in Sansabelts, many with suspect mustaches. The men onscreen aren’t just “nerds” from a safe distance, historically, esthetically, they’re a dozen kind of so-male duffers and bluffers and mopers and dopers. They’re clever but not wise. The loopy existential comedy of Computer Chess reaches a blissful climax that only the film’s ugly, longhaired mash-faced stoner of a cat that wanders the motel’s creepy corridors could have predicted. By the end, it seems not only to have swallowed its own tail but also to have invented itself whole with but a C: prompt and a blinking cursor.

11. The Unspeakable Act, Dan Sallitt. There’s a scene shot in a single extended take, where Jackie (the vital Tallie Medel)  and Matthew (Sky Hirschkron) have peeled off from a group of friends, leaning into each others backs while sitting on a park bench. The light under leafy green trees is gentle, and the sounds of the city and the night precisely present, hush of traffic, a commenting insect. “This is such a perfect night,” Jackie says. “It’s what I wish life could always be like. I know, it’s just a fantasy but it’s very sweet.” A pause. Matthew says, “Maybe it wouldn’t be much fun if it weren’t a fantasy.” “Well, we’ll never know, will we?” Jackie says, and Medel’s little uptick is everything. A pause. “Since when did you get so resigned to your fate?” She has the words, as she often does: “What makes you say that? All my life I’ve known there’s no solution, I don’t have any expectation of us having a life together. I never have.” She pauses. A child’s voice, raised nearby. She continues: “I’m not talking about the unmentionable act, I don’t think that’s such a big deal. I think that’s just a matter of logistics.” He rolls his words wryly: “Or, an unmentionable act that gets mentioned a lot.” “Ahh, ha, don’t that make you uncomfortable? Come on! You like it! You’d be sad if I lost interest. The phase were over. You’d feel abandoned.” These words are good on the page, but spoken aloud, performed, inhabited, murmured and slightly slurred, they are fantastic.

and Matthew (Sky Hirschkron) have peeled off from a group of friends, leaning into each others backs while sitting on a park bench. The light under leafy green trees is gentle, and the sounds of the city and the night precisely present, hush of traffic, a commenting insect. “This is such a perfect night,” Jackie says. “It’s what I wish life could always be like. I know, it’s just a fantasy but it’s very sweet.” A pause. Matthew says, “Maybe it wouldn’t be much fun if it weren’t a fantasy.” “Well, we’ll never know, will we?” Jackie says, and Medel’s little uptick is everything. A pause. “Since when did you get so resigned to your fate?” She has the words, as she often does: “What makes you say that? All my life I’ve known there’s no solution, I don’t have any expectation of us having a life together. I never have.” She pauses. A child’s voice, raised nearby. She continues: “I’m not talking about the unmentionable act, I don’t think that’s such a big deal. I think that’s just a matter of logistics.” He rolls his words wryly: “Or, an unmentionable act that gets mentioned a lot.” “Ahh, ha, don’t that make you uncomfortable? Come on! You like it! You’d be sad if I lost interest. The phase were over. You’d feel abandoned.” These words are good on the page, but spoken aloud, performed, inhabited, murmured and slightly slurred, they are fantastic.

12. The Spectacular Now, James Ponsoldt. Ponsoldt isn’t romanticizing a thing, although his perfectly measured moment of his young couple’s first headlong flirtation that contains a kiss is an exquisitely calibrated thing, a long talk, a long take, full of teasing exchanges and cheek-flushing bravado, captured with bravura directness. The low of late summer crickets accompanies them until it doesn’t, and she says, “I don’t have any ex-boyfriends.” (The camera, which had been moving forward, moves back toward them, cocking to one side ever so slightly: gravity gives.) As in every scene they’re in, Miles Teller and Shailene Woodley are, well, awesome.

13. Blue Is the Warmest Color, Abdellatif Kechiche. Adèle Exarchopoulos be thy name. Kechiche’s camera fixates on Exarchopoulos, and she’s a stand-in, not only for a lesbian character but also for anyone, any youthful first immersion into the physical world of another person. Kechiche captures a staggeringly intense amount of orality: kissing, smoking, talking, spitting, fucking and eating, oh, such eating. As his game gamine, Adèle Exarchopoulos is sexual, and sexualized, but her embodiment of oral desire is ravishing. (She reminds me of a good friend whose efficiency, dispatch and grace at table both amazes and wounds in the same lovely instant.)

13. Blue Is the Warmest Color, Abdellatif Kechiche. Adèle Exarchopoulos be thy name. Kechiche’s camera fixates on Exarchopoulos, and she’s a stand-in, not only for a lesbian character but also for anyone, any youthful first immersion into the physical world of another person. Kechiche captures a staggeringly intense amount of orality: kissing, smoking, talking, spitting, fucking and eating, oh, such eating. As his game gamine, Adèle Exarchopoulos is sexual, and sexualized, but her embodiment of oral desire is ravishing. (She reminds me of a good friend whose efficiency, dispatch and grace at table both amazes and wounds in the same lovely instant.)

14. Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, David Lowery. Deliquescent images: Ruth’s simple white dress in an early scene, lightly cinched with thin rope, barelegged in boots with the tongues nearly loose; a second-story view of a street corner at dawn, similar to a quietly haunting shot in Badlands; a sandwich in wax paper folded just so; fingers tickling the dark under a bar counter, finding, of course, a sawed-off double barrel; shadows as deep as daylight is bright, the warmth of particular shadows that fall to black just past faces. What scenes are not shot at golden hour are shot, boldly, in the hours just beyond. It’s the same commonplace rustication as in his rich, minimal first feature, St. Nick, the story of two children on the run. Spaces and places feel as warmly worn and lived-in as an old man’s boots.

14. Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, David Lowery. Deliquescent images: Ruth’s simple white dress in an early scene, lightly cinched with thin rope, barelegged in boots with the tongues nearly loose; a second-story view of a street corner at dawn, similar to a quietly haunting shot in Badlands; a sandwich in wax paper folded just so; fingers tickling the dark under a bar counter, finding, of course, a sawed-off double barrel; shadows as deep as daylight is bright, the warmth of particular shadows that fall to black just past faces. What scenes are not shot at golden hour are shot, boldly, in the hours just beyond. It’s the same commonplace rustication as in his rich, minimal first feature, St. Nick, the story of two children on the run. Spaces and places feel as warmly worn and lived-in as an old man’s boots.

15. 12 Years A Slave, Steve McQueen. The soundtrack sings with a chorus of the elevated chirr of cricket song, and its rise and fall is matched by the moments McQueen chooses to focus on a telling visual element for a beat or three longer than usual: three blackberries that could yield ink; a forbidden letter’s last, silk-thread-like embers ebbing against blackness; a close-in shot of the industrial churn of the paddlewheel of boat laden with slaves that rises to reveal the eddy and chop of water left behind, still surging, but falling in moments off to nothing. The widescreen tableaux capture the mute beauty of the Louisiana swamps and bayous, but its ugliness, too, as in one of the film’s longest takes, when Solomon is left tangling from a tree branch, inches, inches from suffocation, and life among the slaves must go on around him. (After Solomon wakes in shackles in a shaft of punishing white light, the camera rises, rises along the brick building, up several stories, and stops at the horizon of Washington, the U. S. Capitol in the distance, near but so very far away.)

15. 12 Years A Slave, Steve McQueen. The soundtrack sings with a chorus of the elevated chirr of cricket song, and its rise and fall is matched by the moments McQueen chooses to focus on a telling visual element for a beat or three longer than usual: three blackberries that could yield ink; a forbidden letter’s last, silk-thread-like embers ebbing against blackness; a close-in shot of the industrial churn of the paddlewheel of boat laden with slaves that rises to reveal the eddy and chop of water left behind, still surging, but falling in moments off to nothing. The widescreen tableaux capture the mute beauty of the Louisiana swamps and bayous, but its ugliness, too, as in one of the film’s longest takes, when Solomon is left tangling from a tree branch, inches, inches from suffocation, and life among the slaves must go on around him. (After Solomon wakes in shackles in a shaft of punishing white light, the camera rises, rises along the brick building, up several stories, and stops at the horizon of Washington, the U. S. Capitol in the distance, near but so very far away.)

16. The Great Beauty, Paolo Sorrentino. Can there be such a thing as boisterous lethargy? Tragicomic torpor? Energetic ennui? Sì, sì and sì: in Paolo Sorrentino’s extravagant, confident, magnificent epic, Rome is front and center in all its decaying beauty and insurgent energy, its “disenchantment and cynicism,” with Sorrentino’s protagonist, the journalist Jep Gambardella (Toni Servillo) lending his sad eyes to reflect all of society in front of him.

16. The Great Beauty, Paolo Sorrentino. Can there be such a thing as boisterous lethargy? Tragicomic torpor? Energetic ennui? Sì, sì and sì: in Paolo Sorrentino’s extravagant, confident, magnificent epic, Rome is front and center in all its decaying beauty and insurgent energy, its “disenchantment and cynicism,” with Sorrentino’s protagonist, the journalist Jep Gambardella (Toni Servillo) lending his sad eyes to reflect all of society in front of him.

17. Upstream Color, Shane Carruth. Resistant symbols recur and bloom, as blood and parasite and flora. The largely plein air cinematography (by Carruth) is specific and contemporary and near peerless. But above all it is a sensational accumulation of the resoundingly concrete and gorgeous and specific: that bob of hair above Seimetz’s keenly lost features once her character has given herself over to simple paranoiac reactivity; basins of ice cubes; sheets of inscribed stave paper or of corporate hoo-ha cascading from a bridge down to a river and from a elevated walkway to an emptied lobby; multiple occurrences of the drape of lank fabrics on Seimetz’s form (like each physical detail, the costume design is simple yet exemplary); flexing hands or flexing feet; a woman’s black tights shredded at the toes as toes worry, worry; a plump pale grub sluggish yet undulant against a tan palm, its lines as prominent as the veins on the back of leaf; a hand pocketing a phial of hotel shampoo at waist height; a fearful couple retracting into a cluttered bathroom, embracing, clothed, in the bathtub with an oversize wood axe at hand.

17. Upstream Color, Shane Carruth. Resistant symbols recur and bloom, as blood and parasite and flora. The largely plein air cinematography (by Carruth) is specific and contemporary and near peerless. But above all it is a sensational accumulation of the resoundingly concrete and gorgeous and specific: that bob of hair above Seimetz’s keenly lost features once her character has given herself over to simple paranoiac reactivity; basins of ice cubes; sheets of inscribed stave paper or of corporate hoo-ha cascading from a bridge down to a river and from a elevated walkway to an emptied lobby; multiple occurrences of the drape of lank fabrics on Seimetz’s form (like each physical detail, the costume design is simple yet exemplary); flexing hands or flexing feet; a woman’s black tights shredded at the toes as toes worry, worry; a plump pale grub sluggish yet undulant against a tan palm, its lines as prominent as the veins on the back of leaf; a hand pocketing a phial of hotel shampoo at waist height; a fearful couple retracting into a cluttered bathroom, embracing, clothed, in the bathtub with an oversize wood axe at hand.

18. Fruitvale Station, Ryan Coogler. While pumping gas, Oscar sees a stray dog on the apron of the station and plays with it. After he turns away, we hear the sound of it being hit by a car, and Oscar yells after the hit-and-run driver. He holds the bloodied dog in his arms. Sudden, shocking, senseless: no one hears Oscar’s cries for help. He returns to his car, the moment held in a wide long shot. Was that rank symbolism? What happens next is the true punch: behind the station, we see now there are elevated tracks, as we hear the harsh whisper-rush of a BART train entering, then exiting the frame. That’s where I just stopped breathing for a moment: potentially blunt dramaturgy turns to something profound (and not perfumed) in implication. The fatedness is not limited to the train, to another train that will take he and his friends and his girlfriend to Fruitvale Station in a few hours, it’s everywhere. Every cop. Every corner.

19. Frances Ha, Noah Baumbach. As her roommate and best friend from college, Sophie, Mickey Sumner is somnolent but coiled, snappish but attentive, precisely sour. She makes Sophie an ideal counterpoint to the innately dorky Frances, bristling if not precisely hostile to her friend’s teeming Frances-ness. There are men, too, foils and acolytes but none of them the motor of the movie or her prepossessed life.

19. Frances Ha, Noah Baumbach. As her roommate and best friend from college, Sophie, Mickey Sumner is somnolent but coiled, snappish but attentive, precisely sour. She makes Sophie an ideal counterpoint to the innately dorky Frances, bristling if not precisely hostile to her friend’s teeming Frances-ness. There are men, too, foils and acolytes but none of them the motor of the movie or her prepossessed life.

20. Enough Said, Nicole Holofcener. Oh, Julia Louis-Dreyfus. Oh, James Gandolfini. Enough Said, as with earlier Holofcener titles, like Please Give and Friends With Money, seems hardly to qualify as a title, more like a designation, or a Post-It with a provisional squiggle on it. But, even more than Woody Allen’s often-lackadaisical monikers, once the credits roll, her titles punch and hug and hold.

20. Enough Said, Nicole Holofcener. Oh, Julia Louis-Dreyfus. Oh, James Gandolfini. Enough Said, as with earlier Holofcener titles, like Please Give and Friends With Money, seems hardly to qualify as a title, more like a designation, or a Post-It with a provisional squiggle on it. But, even more than Woody Allen’s often-lackadaisical monikers, once the credits roll, her titles punch and hug and hold.

21. Spring Breakers, Harmony Korine. “Fugue” was a word I wrote down too many times on first exposure at Toronto 2012: an impression not of a sustained, traditional narrative, but of a gallery installation of a loop, or at an immense electronic music show, something that could be playing on four walls at once, brightness and color bouncing off one screen, another, another. Dialogue’s treated the same way, another texture among waves of texture. But part of Korine’s thrust is first to take the obvious, then repeat it—can the most earnest of the girls be unironically named “Faith”?—to thrive on mixed messages.

21. Spring Breakers, Harmony Korine. “Fugue” was a word I wrote down too many times on first exposure at Toronto 2012: an impression not of a sustained, traditional narrative, but of a gallery installation of a loop, or at an immense electronic music show, something that could be playing on four walls at once, brightness and color bouncing off one screen, another, another. Dialogue’s treated the same way, another texture among waves of texture. But part of Korine’s thrust is first to take the obvious, then repeat it—can the most earnest of the girls be unironically named “Faith”?—to thrive on mixed messages.

22. Stray Dogs, Tsai Ming-liang. Long takes, lustrous gloom, and obsessive and hypnotic compositions that make Taiwan seem like another planet. One scene is captured in a take as lengthy as the opening shot of Gravity of a man eating a huge, head-sized cabbage after practicing a terrible thing to the sound of never-ending rain. His images are both terrible and beautiful.

22. Stray Dogs, Tsai Ming-liang. Long takes, lustrous gloom, and obsessive and hypnotic compositions that make Taiwan seem like another planet. One scene is captured in a take as lengthy as the opening shot of Gravity of a man eating a huge, head-sized cabbage after practicing a terrible thing to the sound of never-ending rain. His images are both terrible and beautiful.

23. The Sun Don’t Shine, Amy Seimetz. A gem of concision and dreaminess, of dread and threat, Seimetz’s Central Florida neo-noir is fluid, fluent and tactile. The human mystery has nuance in every life and transaction, but Seimetz manages to work through and beyond the often-limited range of the murder drama, and find further portent in the relentless freakishness that is Florida. There’s a joyful dank in almost every moment, in all its swampy glory and prickly paranoia. Sun Don’t Shine is like a slow long freight train you hear in the distance on a semi-sleepless summer night; it never comes closer, it never goes farther, it does not end, the sound does not end.

23. The Sun Don’t Shine, Amy Seimetz. A gem of concision and dreaminess, of dread and threat, Seimetz’s Central Florida neo-noir is fluid, fluent and tactile. The human mystery has nuance in every life and transaction, but Seimetz manages to work through and beyond the often-limited range of the murder drama, and find further portent in the relentless freakishness that is Florida. There’s a joyful dank in almost every moment, in all its swampy glory and prickly paranoia. Sun Don’t Shine is like a slow long freight train you hear in the distance on a semi-sleepless summer night; it never comes closer, it never goes farther, it does not end, the sound does not end.

24. Behind The Candelabra, Steven Soderbergh. Soderbergh-ian to a fare-the-well. Side Effects has virtues, too, but what may be the protean filmmaker’s most influential project of the year is embedded below after # 25.

25. The World’s End, Edgar Wright. Gary King is stuck in place because of his stunted nostalgia, looking for the final moment to weep over “all that promise and fucking optimism.” The low and high merge bumptiously at any given moment, and the swearing, while comic and calibrated, is near ubiquitous and tilting with verbal splendor. Gary’s greeting to his mates, arriving late at the train station, is quintessential King: “Look at these —-s!”

25. The World’s End, Edgar Wright. Gary King is stuck in place because of his stunted nostalgia, looking for the final moment to weep over “all that promise and fucking optimism.” The low and high merge bumptiously at any given moment, and the swearing, while comic and calibrated, is near ubiquitous and tilting with verbal splendor. Gary’s greeting to his mates, arriving late at the train station, is quintessential King: “Look at these —-s!”

State of Cinema: Steven Soderbergh from San Francisco Film Society on Vimeo.

And, alphabetically, thirty-five more entertainments.

All Is Lost. J. C. Chandor. “Fuck!”

American Hustle, David O. Russell. Jennifer Lawrence, just getting started. Sweet hopping Jesus.

The Bling Ring, Sofia Coppola. Selfie-knowledge: this based-on-fact fairytale is very much like her four earlier fairytales, sharing one keen characteristic. Aloneness: Coppola’s great subject. To be among others and yet so very alone. (Like any proper reader of fairytales as well.) One of the loveliest and most disturbing scenes in a robbery that takes place in a two-story glass box of a home in the Hollywood Hills, with the camera watching from higher up as the delinquents move from room to room, turning lights on and off, tiny figures we cannot hear, but there are helicopters in the distance, a siren a mile away, and yes, that was a coyote over there. There’s a darkened pool in the foreground, and then the guttering gleam of the basin’s lights on the horizon far below beneath a chalk-to-bone-gray night sky. It’s architectural-topographical comedy. But also, in that tranquil, composed scene, the film demonstrates that the world, the city, the culture around them is oblivious. They’re another small, unnoticed activity on the desert floor, not paparazzi bait, but scavengers on the level of that coyote.

Blue Jasmine, Woody Allen. For Cate Blanchett’s roaring appetite, a few sweet moments with Louis C. K. and Allen’s capacity to make San Francisco look like a proper slum.

Berberian Sound Studio, Peter Strickland. The clammy production design, swaddling in shadow, manages to be both rubicund and cloacal, and the apocryphal film being mixed sounds like a brilliant replica of a barrel-scraping Giallo movie of the time, down to a gorgeous, trashy title sequence.

Drinking Buddies/All The Light In The Sky, Joe Swanberg. Measures of unflurried naturalism.

The East, Zal Batmanglij. We could use a new Pakula or two.

Fill The Void, Rama Burshtein. One heart-stopping moment blocked and acted and refracted in a matter of millimeters: A man and a woman, alone, on a path at night, forbidden to touch, speak, confront, describe passion: the man moves closer. That’s all. The smallest of moves, infinitesimal motion. The world tilts on its axis.

Gloria, Sebastián Lelio. Paulina Garcia is golden.

Hannah Arendt, Margarethe von Trotta. Barbara Sukowa, ja.

Hors Satan (2011, U. S. release 2013), Bruno Dumont. Dumont’s final feature with the late David Dewaele is as hypnotic as their collaboration in Hadewijch, another lucid hallucination splendid with sex, demons and landscapes that could have been painted centuries ago.

How I Live Now, Kevin Macdonald. Ordinary life, that’s what’s endangered by catastrophe, not politics or privilege, the film demonstrates with quiet assurance. We get only glimpses of damage, glimmers of ruin, including marshmallows around the fire being disturbed by sounds from distant, distant, so distant London, followed quickly by pillowy ash piling from the sky and whitening the setting’s verdant embrace.

The Hunt, Thomas Vinterberg. Charlotte Bruus Christensen’s lighting is slightly misty, often shooting toward light sources, a halation effect that quietly captures impermanence, the events playing like a memory that remains unfixed.

I Used To Be Darker, Matt Porterfield. Most every music cue in Darker comes from an onscreen source: sometimes the most practical notion is the most fruitfully aleatory. Jeremy Saulnier’s summer-spent cinematography is gentle and nothing shy of exquisite.

I’m So Excited!, Pedro Almodóvar. The reigning raunchiness elevates the brute cynicism of the film’s disappointed politics.

The Immigrant, James Gray. As Andrew Sarris would have said, a subject for further research. It’ll be a shame if this dreamy apparition of collective memory doesn’t see the big screen, with adequate projection.

Laurence Anyways, Xavier Dolan. Dolan’s style can appear overheated, flamboyant, baroque, immature, indulgent, extravagant, but it is what it is and what it is, at his keenest moments, is fabulous.

Lore, Cate Shortland. This is what movies can look like, with casting, color, composition, tempo: they can be tactile, empathetic, empathic, detailed, suggestive, bold, fragile and altogether a thing of life and dream at once. The blue of inked numerals on forearm effaced by tugging down a deep blue wool sleeve; glisten of child’s blue eyes above rudely blushing mouth; ants prickling at vinous red darkened onto a bloodied thigh; figurines emblematic of innocence crushed with grown-ups’ finality: painterly yet photographic conjuring.

Nebraska, Alexander Payne. The third-generation Greek-American filmmaker’s most Greek film ever. The native Omahan’s features show respect for multiple generations merely by paying attention to them, as well as how they refract one another. The ceaseless verbal belittling is very Greek, indeed. And the old man and the middle-aged man returning to the village each with their own idea of what “the past” means is a story that Greece’s best-known filmmaker, the late, great Theo Angelopoulos returned to more than once, in movies like Voyage to Cythera. Angelopoulos used that journey, both physical and psychic, to capture the return to the homeland that is innocence, to which, of course, there is no return. For Payne and Angelopoulos alike, there are legends and landscapes and a succession of ruins.

Only Lovers Left Alive, Jim Jarmusch. What goes around goes around. And goes around.

Pacific Rim, Guillermo del Toro. The set of determined faces is matched by marvelous costume design that brings it all to human, textural level. Fabrics feel weathered, worn, timeless, classic, wonders of sensation. The slightest tweaking of a seam along the shoulder of a young man’s sweater; the wool-to-linen burst along the hard, pressed crease of Stacker Pentecost’s blue gabardine-ish suit jackets; shoes. Shoes that suit the scenes. Shoes that suit the characters. Little red shoes that make the past explode into the shared memories of two Jaeger pilots. There’s so much onscreen, so much suggested but not explored or explained, almost like jam-packed Harvey Kurtzman panels from classic MAD magazines, detailed by the likes of a Romanek or a Tarsem. It’s joyous even as cities are leveled by the pure malevolence of the Kaiju.

The Past, Asghar Farhadi. Life’s only a matter of perspective, but the perspective is ever-shifting. Every element is relentlessly, restlessly suggestive: so many windows, so many frames filling the film’s décor: voices raised but muted behind windows in an airport; the view through wrought-iron fences; the gridding of safety mesh on an overpass; low, unexpected sets of stairs; hands in the pass between a dining room and a kitchen; smoking at a French door open to a balcony by night; faces peering through just-opened doors; a hoarding on a wet street shimmering a blank red; the clatter of overlapping empty picture frames lined up in front of a window in a frame-builder’s workshop.

The Place Beyond The Pines, Derek Cianfrance. Ben Mendelsohn remains the silkiest, most magnetic of contemporary character actors: gentle, louche, ever-threatening. Brilliant blue eyes chill: Cooper’s are lit blue-to-emerald and while corners of scenes drop to shadow or shade, Gosling, Cooper and Mendelsohn’s eyes gleam cold and proud and perhaps just a little fearful. The young actors of the third panel of the triptych have their own evolution of the essential conflicts: the ghost of Nicholas Ray cocks an eyebrow with great interest.

Post Tenebras Lux, Carlos Reygadas. Beauty and debasement: it’s Reygadas’ stock in trade, along with blighted naturalism and subtropical maladies that pass for elusive cultural critique.

Prince Avalanche, David Gordon Green. Tim Orr’s cinematography is rustic and dreamy at once: there’s no barrier between the present and the lingering memories of the still-scorched forest. Between here and now and memory and limbo. You never know, when miracles happen.

Prisoners, Denis Villeneuve. An amorality tale, dotted with beating and shooting and torture and swearing, but also with a pang of melancholy, shame for the potential of ignominy in good intentions, all of ours. Two more words: Roger Deakins.

The Selfish Giant, Clio Bernard.

The sky is gray and low by day and night seems limitless. Once-industrial lands have grown over, industry has gone and grass and greenery grow wild. The landscape is dotted with railway tracks, electrical transmission towers, triads of disused power station cooling towers stand like ancient altars no longer used for sacrifice, swaddled in eggshell-to-gray fogs; sheep graze, simply. The small shaggy horse with its cart is tinier still in landscape, another way of scaling the world against these lost boys.

Short Term 12, Destin Cretton. Fierce, honest, reflecting her character’s substantial conflicts, suggestive of deeper and deeper currents, Brie Larson offers the kind of performance that actors beg for but nearly never find in larger, more costly movies.

Simon Killer, Antonio Campos. Campos’ Paris by night shares some of the crazy stylized palette of Michael Chapman’s work on Taxi Driver. And the sound design is exemplary: we often hear the music in his earbuds, Simon’s subjective choice, rather than the sound of the street. Much is unexplained, yet it’s exhilarating to have character implied by the soundscape rather than text.

Stranger By The Lake, Alain Guiraudie. A “documentary thriller,” and a kind of full-frontal Hitchcock: The choreography, the unacknowledged dance of desire as the characters arrive, peruse, transact, mimics other forms of attraction, repulsion, human interactions. The characters situate themselves in the landscape in hope of sexual exchange, but also as figures in the landscape, like figures in a painting. Across the ten days of the story, the setting establishes itself as its own “normality.”

To The Wonder, Terrence Malick. The film’s most tender moment, even aside from caresses in chaste nudity that are new to Malick, is between Neil and Jane. In a too-brief passage, Jane, who appears to be a horse rancher, finds herself and Neil brushing against each other in a large field against empty horizon right up next to a herd of brown bison amid rustling grasses, as if grass were ever still when a camera is directed its way. The wind buffets Jane’s loose hair, she and Neil kiss, and a single, ready tear trembles on her cheek, matching a pearl earring to the side of her face, the side of the frame. “I love you,” she whispers and all is good, before Malick is quickly back to God, wind, sun, murmuring.

Vic + Flo ont vu un our. Denis Côté. Denis Côté, murderer of genre.

Wadjda, Haifaa Al-Mansour. Ten-year-old Wadjda is a kind of supergirl, an unstemmable entrepreneur, who even masters the Koran for a competition among other schoolgirls, her eyes always on the prize: the gleaming symbol of self, that majestic shiny green and white ride. The good and hopeful ending will get you.

What Maisie Knew, Siegel/McGhee. The eyes of a child. The forgiving of adults. The look of how lives inhabit certain spaces.

When Evening Falls on Bucharest or, Metabolism, Corneliu Porombui. How dry can dry get? Dry. Delirious understatement from a minimalist master.

The Wolf Of Wall Street, Martin Scorsese. Willful Wolf leaves us as one more mark: this particular image is only a few seconds long, but it provides a savage silence, a pall is cast, and oh-so-quickly, in a fine coup de théâtre, a moral moment has passed.

Anticipating: Can A Song Save Your Life?, Closed Curtain, Club Sandwich, The Counselor, The Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby, The Double, Enemy, A Field In England, Joe, Mud, Pain & Gain, The Selfish Giant, The Strange Little Cat, Top of the Lake, Viola, We Are The Best, The Wind Rises, You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet.

Ted Sarandos, Netflix Chief Content Officer

Scorsese’s IT’S JUST NOT YOU, MURRAY (1964) (15’41”)

Plus, Scorsese and Schoonmaker in the edit suite, for Life Lessons, with Michael Powell.

Trailering SOIGNE TA DROITE with J.-L. Godard et Les Rita Mitsouko (3’07”)

[V. @tnyfrontrow]

THE MAN WHO PLANTED TREES (30’06”) (1987) RIP Frédéric Back

On The Pale, Pastel Colors Of INSIDE LLEWYN DAVIS

[American Cinematographer, January 2014.]

Wes Anderson Offers Up The Cast Of THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL (1’35”)

Joseph O. Holmes’ “A tribute to the projection booth” (12’02”)

[Details.]

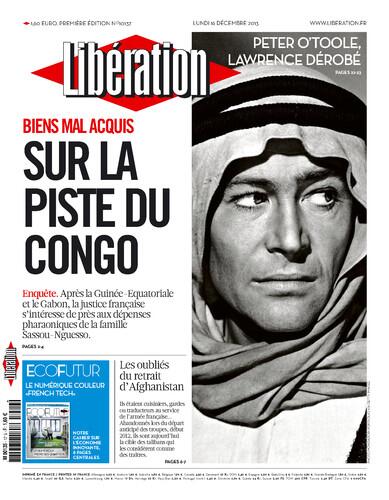

Peter O’Toole in “Jeffrey Bernard Is Unwell” (2’03″22′)

The complete performance of Keith Waterhouse’s 1989 play, at the Old Vic Theatre, London.

1 Comment »