Movie City Indie Archive for January, 2015

TIFF 2014 Panel On Hou Hsiao-hsien With Good Dr. Bordwell, Bart Testa, James Udden (88 minutes)

George Lucas And Robert Redford Talk “Power Of Story” With Leonard Maltin (113 minutes)

Sundance Seen Part 1

Three girl ghosts at dusk.

Infernal. Everyday sight if you get around town, or if you just like sitting in traffic. (Or don’t take a taxi, or don’t like to say, “We’ll Uber it” or “That your Uber,” two of the more common phrases this year.

Never an empty rack: is no one picking up the Reporter?

Up the hill on Main Street, wildposting is done in the proper place for Slamdance in front of the Treasure Mountain Inn. (Chicago filmmaker Michael Olenick, left.)

A promotion at the International Documentary Association’s fete for the fine, compassionate screengrab-of-our-moment doc by Jill Bauer and Ronna Gradus.

Don’t ask what happened here. It can’t be unseen.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning Jonathan Gold, food critic of the Los Angeles Times and subject of Land Of Gold, has a moment with Film Quarterly editor Ruby B. Rich in the Mariott headquarters hallway.

Breezing past the nineteenth century children’s cemetery.

And in between movies, slices of the Utah sky.

Pop-ups everywhere in Park City for the ten days of Sundance. Not all of them connected to Evel Knievel.

On Main Street, Kevin Smith is smodded by fans outside a popup Tim Horton’s somehow in support of his later-in-the year Yoga Hosers. “I never saw myself making a kid’s movie,” he told me, “but I think it came out kinda good.”

RIP Continuity Supervisor Jane Randall; Projects Including THE SHINING (3’47”)

With behind-the-scenes photos.

Trailering Assayas’ CLOUDS OF SILS MARIA (2’23”)

In theaters April 10.

Scorsese Directs De Niro And DiCaprio In Two Casino Commercials (2 x 1’00”)

… with more on the way.

Best of 2014: A Top 40

1. Boyhood, Richard Linklater. Linklater is one of the few filmmakers you’d expect to foresee the fact that he would be shooting a period piece in the present: that is, that each year would be seen from a distance of years, and however the present was characterized, through pop culture and other social artifacts, would accrue into simple nostalgia. But Linklater’s better than that, and the ending, the very ending, is open-ended yet also a summation of what so many of his wanderers have been searching for all their on-screen lives. Boyhood is perfectly imperfect, and surely not the last exploration of feature filmmaking as the ideal form to encapsulate duration and unities of location to come from the dogged, invaluable fifty-three-year-old writer-director. Time. Time itself. As much as any of Linklater’s movies, Boyhood fits squarely into the exquisite expanses of one of my favorite poems, my fellow Kentuckian Robert Penn Warren’s “Audubon: a vision”:

1. Boyhood, Richard Linklater. Linklater is one of the few filmmakers you’d expect to foresee the fact that he would be shooting a period piece in the present: that is, that each year would be seen from a distance of years, and however the present was characterized, through pop culture and other social artifacts, would accrue into simple nostalgia. But Linklater’s better than that, and the ending, the very ending, is open-ended yet also a summation of what so many of his wanderers have been searching for all their on-screen lives. Boyhood is perfectly imperfect, and surely not the last exploration of feature filmmaking as the ideal form to encapsulate duration and unities of location to come from the dogged, invaluable fifty-three-year-old writer-director. Time. Time itself. As much as any of Linklater’s movies, Boyhood fits squarely into the exquisite expanses of one of my favorite poems, my fellow Kentuckian Robert Penn Warren’s “Audubon: a vision”:

Tell me a story.

In this century, and moment, of mania,

Tell me a story.

Make it a story of great distances, and starlight.

The name of the story will be Time,

But you must not pronounce its name.

Tell me a story of deep delight.

2. Gone Girl, David Fincher. The hyperbolic, galvanic, filthy-black-funny Gone Girl is multitudes. And it’s one of the most complexly disturbing movies about grownups fucking up sex in all too long. Sex, no, not sex, really, but power. Who has the fucking upper hand and who has the upper hand fucking? (Oh, the music in Rosamund Pike’s voice when her “Amazing Amy” first beds Nick and says, as he tousles his face upon her lap in an act of assured cunnilingus, “Nick Dunne, I really like you.”) And every bit of it is so readily read into, and not limited to various and sundry accusations of misogyny in the narrative. Gone Girl is unreliable narration atop unreliable narration. A second viewing was nearly as unnerving as the first: there’s three sides to every story, yours mine and the cold, hard truth; Fincher and Flynn have their cake, your cake and eat it too, in meta-meta commentary of the modern moment of media and what none dare call “relationships.” Cut at a sweetly punishing clip, Gone Girl refracts so many attitudes about the cupidity of human desire and the rapidity of the fall when attempts to fuck up another person fuck you up in turn.

3. The Immigrant, James Gray. Where Bruno binds Ewa to bed and pulls her to ground, speaking always of cash, Emil climbs in windows through fire escapes, brandishes postcards of the beautiful California seaside (which, cannily, we are not allowed to glimpse) and at one inexplicable moment of implausible, fantasticated beauty, merely levitates. In a world of soot and muck and views warped by crudely annealed, light-bending, feature-distorting window glass, Emil promises life can become lighter than air, where once all that is profaned could become sacred once more. While the locations and panoramas are limited (to effective budgetary and esthetic effect), the ghostly dreaminess of The Immigrant lies in its realization of the state of mind of its characters, each imbued with hope no matter how quickly they become a “soiled dove,” as Bruno coos at Ewa. These are the ones that had a hope that was handed down to generations. And yet we know that when Emil says in one of his performances, “Don’t give up the faith, don’t give up the hope, the American Dream is waiting for you!” it is as much threat as promise, but it is a threat and promise upon which our America, now, is built. It is a brilliant rebuke to the making of myth. Its heart is pure.

3. The Immigrant, James Gray. Where Bruno binds Ewa to bed and pulls her to ground, speaking always of cash, Emil climbs in windows through fire escapes, brandishes postcards of the beautiful California seaside (which, cannily, we are not allowed to glimpse) and at one inexplicable moment of implausible, fantasticated beauty, merely levitates. In a world of soot and muck and views warped by crudely annealed, light-bending, feature-distorting window glass, Emil promises life can become lighter than air, where once all that is profaned could become sacred once more. While the locations and panoramas are limited (to effective budgetary and esthetic effect), the ghostly dreaminess of The Immigrant lies in its realization of the state of mind of its characters, each imbued with hope no matter how quickly they become a “soiled dove,” as Bruno coos at Ewa. These are the ones that had a hope that was handed down to generations. And yet we know that when Emil says in one of his performances, “Don’t give up the faith, don’t give up the hope, the American Dream is waiting for you!” it is as much threat as promise, but it is a threat and promise upon which our America, now, is built. It is a brilliant rebuke to the making of myth. Its heart is pure.

4. The Grand Budapest Hotel, Wes Anderson. Anderson’s everyman-in-no-man’s-land is Gustave H., the concierge of an ocean liner of a wedding-cake deluxe hotel in the fictional duchy of Zubrowka, The Grand Budapest Hotel. He is a man with a job, if not a surname or a notable nationality. Ralph Fiennes invests H. with the brusque panache of both the boulevardier and the comic lights of the stage. Lubitsch’s blithe cosmopolitanism is supplanted by brute snippiness in the person of Fiennes. Speaking faster than he fast-walks, his H. is given to “oh fuck it”s that are the verbal equal of Indiana Jones choosing to take out a pistol and dispatch a scimitar-wielding opponent. (Fiennes is nourished by H.’s bursts of comic filth.) His impatience, his hurry, accelerates the sense that a narrative, an era, is hurtling to a close, as well as setting the tempo for the heist-and-chase design of this lovely, if bittersweet accomplishment.

4. The Grand Budapest Hotel, Wes Anderson. Anderson’s everyman-in-no-man’s-land is Gustave H., the concierge of an ocean liner of a wedding-cake deluxe hotel in the fictional duchy of Zubrowka, The Grand Budapest Hotel. He is a man with a job, if not a surname or a notable nationality. Ralph Fiennes invests H. with the brusque panache of both the boulevardier and the comic lights of the stage. Lubitsch’s blithe cosmopolitanism is supplanted by brute snippiness in the person of Fiennes. Speaking faster than he fast-walks, his H. is given to “oh fuck it”s that are the verbal equal of Indiana Jones choosing to take out a pistol and dispatch a scimitar-wielding opponent. (Fiennes is nourished by H.’s bursts of comic filth.) His impatience, his hurry, accelerates the sense that a narrative, an era, is hurtling to a close, as well as setting the tempo for the heist-and-chase design of this lovely, if bittersweet accomplishment.

5. Love Is Strange, Ira Sachs. Drama seeps in, sensation is suggested. The film’s quietly detailed, lived-in, loved-in feel is both emotionally specific and painterly in its suggestive formal sensations. (Sachs cites the work of American painter Fairfield Porter as a key visual touchstone.) Among his cast, which extends two generations, each figure walks in geometry. Each character has a specific fashion of holding space. Love is Strange is about, yes, love, and about family and about the necessity of generations sharing knowledge and secrets, yet there’s not a line of dialogue that announces this. Love is Strange also bears the acuteness, the precision of the era the characters would have lived through. Buried deep beneath the surfaces, surely there are submerged fragments of Frank O’Hara and his fragrant, antic verse as well as the lore of the painters who frequented and illuminated the interior life of lairs like the Cedar Tavern. The succession of setting and framings are beautiful for their precision and coolness, from strong design rather than a prurient glow.

5. Love Is Strange, Ira Sachs. Drama seeps in, sensation is suggested. The film’s quietly detailed, lived-in, loved-in feel is both emotionally specific and painterly in its suggestive formal sensations. (Sachs cites the work of American painter Fairfield Porter as a key visual touchstone.) Among his cast, which extends two generations, each figure walks in geometry. Each character has a specific fashion of holding space. Love is Strange is about, yes, love, and about family and about the necessity of generations sharing knowledge and secrets, yet there’s not a line of dialogue that announces this. Love is Strange also bears the acuteness, the precision of the era the characters would have lived through. Buried deep beneath the surfaces, surely there are submerged fragments of Frank O’Hara and his fragrant, antic verse as well as the lore of the painters who frequented and illuminated the interior life of lairs like the Cedar Tavern. The succession of setting and framings are beautiful for their precision and coolness, from strong design rather than a prurient glow.

6. We Are The Best!, Lukas Moodysson. What brought Moodysson back to the deliriousness of early movies like Show Me Love (Fucking Åmål)? Love. Love for his wife, Coco. Love for her stories of unstemmable punk girlhood. Punk lives! (and how!).

6. We Are The Best!, Lukas Moodysson. What brought Moodysson back to the deliriousness of early movies like Show Me Love (Fucking Åmål)? Love. Love for his wife, Coco. Love for her stories of unstemmable punk girlhood. Punk lives! (and how!).

7. Ida, Paweł Pawlikowski. There are surely ample footnotes to be made about photographic influence, but what matters is what has been made from influence: a movie that feels like it is a window looking into the distant past, in a format and fashion akin to its era, but which also feels contemporary, timeless and never anachronistic. It is a movie in its moment, but also of its moment: Pawlikowski, and only Pawlikowski, could only have made it in this moment. Shot to shot, each and every element thrills. While the non-actor Agata Trzebuchowska is superb in indicating near-silent acknowledgment of all that swirls around her, Agneta Kulesza, with superlative presence, is the star of the show in every frame she enters or exits, electric with boundless passion, heedless fury, thwarted hope, vital cynicism passed from cigarette end to cigarette end.

7. Ida, Paweł Pawlikowski. There are surely ample footnotes to be made about photographic influence, but what matters is what has been made from influence: a movie that feels like it is a window looking into the distant past, in a format and fashion akin to its era, but which also feels contemporary, timeless and never anachronistic. It is a movie in its moment, but also of its moment: Pawlikowski, and only Pawlikowski, could only have made it in this moment. Shot to shot, each and every element thrills. While the non-actor Agata Trzebuchowska is superb in indicating near-silent acknowledgment of all that swirls around her, Agneta Kulesza, with superlative presence, is the star of the show in every frame she enters or exits, electric with boundless passion, heedless fury, thwarted hope, vital cynicism passed from cigarette end to cigarette end.

8. Calvary, John Michael McDonough. Calvary is, in a very specific way, a “B” movie, by which I mean, “Bergman, Buñuel and Bresson,” Ireland, day: Man walks into a confession booth and tells a priest of terrible things that had been done to him by a priest when he was small. Tells the priest: I’ll get back at the church by killing an innocent priest in one week, and that’s you, get your life in order. Now there’s a set-up. The second feature by writer-director John Michael McDonagh, fills that week full-to-bursting with a raft of idiosyncratic characters and philosophical conflicts and the current crisis in the Church and idiomatic comic dialogue strung along by the script’s thriller-like ticking clock. Brendan Gleeson’s Father James could very well be his best performance in a great career. (Gleeson told me it’s his favorite role.) Graham Greene divided his books into two classes: the novels, which took on spiritual matters, and the lighter ones, which he called “entertainments.” McDonagh’s knack is to combine both the novelistic, spiritual elements of Greene and lighter notes to achieve a high level of gratifying entertainment.

8. Calvary, John Michael McDonough. Calvary is, in a very specific way, a “B” movie, by which I mean, “Bergman, Buñuel and Bresson,” Ireland, day: Man walks into a confession booth and tells a priest of terrible things that had been done to him by a priest when he was small. Tells the priest: I’ll get back at the church by killing an innocent priest in one week, and that’s you, get your life in order. Now there’s a set-up. The second feature by writer-director John Michael McDonagh, fills that week full-to-bursting with a raft of idiosyncratic characters and philosophical conflicts and the current crisis in the Church and idiomatic comic dialogue strung along by the script’s thriller-like ticking clock. Brendan Gleeson’s Father James could very well be his best performance in a great career. (Gleeson told me it’s his favorite role.) Graham Greene divided his books into two classes: the novels, which took on spiritual matters, and the lighter ones, which he called “entertainments.” McDonagh’s knack is to combine both the novelistic, spiritual elements of Greene and lighter notes to achieve a high level of gratifying entertainment.

9. Winter Sleep, Nuri Bilge Ceylan. Ceylan’s usual cinematographer, Gokhan Tiryaki, fixes on landscape in interiors as well as exteriors: he and Ceylan are patient poets of the human face.

9. Winter Sleep, Nuri Bilge Ceylan. Ceylan’s usual cinematographer, Gokhan Tiryaki, fixes on landscape in interiors as well as exteriors: he and Ceylan are patient poets of the human face.

10. Actress, Robert Greene. Life as performance, personality as melodrama, persona as hope. This is the film I’d hoped a filmmaker as intelligent and driven as Robert Greene would make someday, but so soon? His intimate collaboration with his neighbor, actress and mother Brandy Burre is a dazzling singularity, a film to be seen and seen again as much as described to whomever you’re watching it with next.

10. Actress, Robert Greene. Life as performance, personality as melodrama, persona as hope. This is the film I’d hoped a filmmaker as intelligent and driven as Robert Greene would make someday, but so soon? His intimate collaboration with his neighbor, actress and mother Brandy Burre is a dazzling singularity, a film to be seen and seen again as much as described to whomever you’re watching it with next.

11. Citizenfour, Laura Poitras. Edward Snowden’s loquacity in describing the responsibility of a governed citizenry, as well as the elemental passion he expresses for American ideals, stand in stark contrast to the grandstanding of onscreen politicos and spooks, and elevate what could be merely technical talk about “metadata in aggregate” and how billions of conversations could be (and are) siphoned into the data coffers of the government and its contractors each day to something approaching manifesto. The imperturbable calm of the penetrating filmmaking of Citizenfour holds reservoirs of disappointment, anger and finally, wellsprings of hope.

11. Citizenfour, Laura Poitras. Edward Snowden’s loquacity in describing the responsibility of a governed citizenry, as well as the elemental passion he expresses for American ideals, stand in stark contrast to the grandstanding of onscreen politicos and spooks, and elevate what could be merely technical talk about “metadata in aggregate” and how billions of conversations could be (and are) siphoned into the data coffers of the government and its contractors each day to something approaching manifesto. The imperturbable calm of the penetrating filmmaking of Citizenfour holds reservoirs of disappointment, anger and finally, wellsprings of hope.

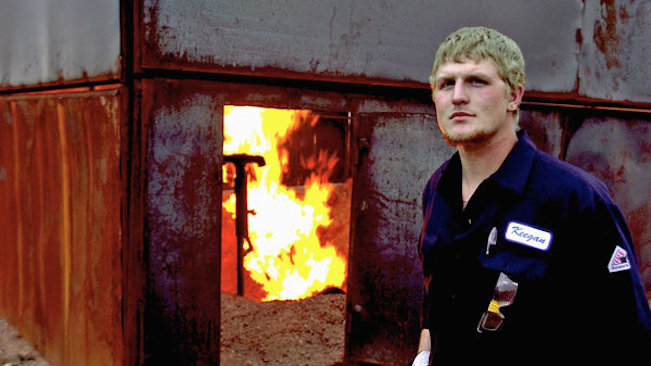

12. The Overnighters, Jesse Moss. Rich with hope and rife with despair, going in as many unexpected directions as life can offer. T. Griffin’s score is elemental to the melancholy of Moss’ mosaic of men in need: it’s as layered as the rest of the assured, compassionate, even brilliant filmmaking.

12. The Overnighters, Jesse Moss. Rich with hope and rife with despair, going in as many unexpected directions as life can offer. T. Griffin’s score is elemental to the melancholy of Moss’ mosaic of men in need: it’s as layered as the rest of the assured, compassionate, even brilliant filmmaking.

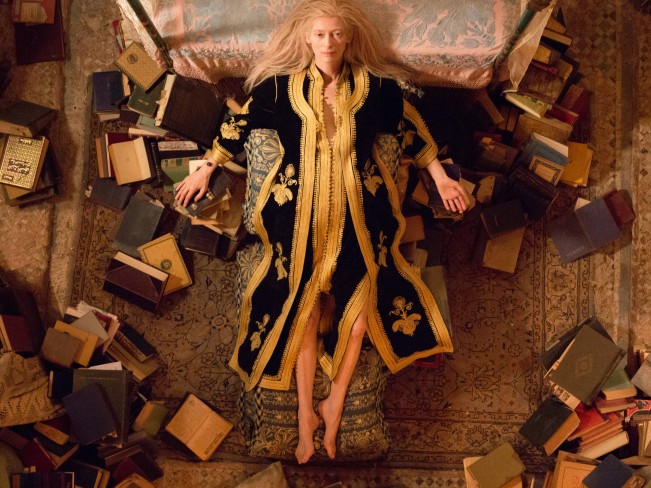

13. Only Lovers Left Alive, Jim Jarmusch. Superficially a vampire story—and one that portrays the soft rush of ingested blood like the hard rush of injected heroin—Only Lovers Left Alive is also a moving meditation on shifting roles in long-term relationships, on “zombie” culture outside the cluttered, cloistered lair, on the eternal promise and disappointment of youth. Keenly, Only Lovers demonstrates the importance of knowing who, in a couple, will be the one to dream and hold fast while the other might flag and despair. It’s also an impeccably furnished paean to cultivated taste in which its practitioners have had centuries to also develop impeccable self-awareness.

13. Only Lovers Left Alive, Jim Jarmusch. Superficially a vampire story—and one that portrays the soft rush of ingested blood like the hard rush of injected heroin—Only Lovers Left Alive is also a moving meditation on shifting roles in long-term relationships, on “zombie” culture outside the cluttered, cloistered lair, on the eternal promise and disappointment of youth. Keenly, Only Lovers demonstrates the importance of knowing who, in a couple, will be the one to dream and hold fast while the other might flag and despair. It’s also an impeccably furnished paean to cultivated taste in which its practitioners have had centuries to also develop impeccable self-awareness.

14. Force Majeure, Ruben Östlund. A ticklish mix of Billy Wilder (visual wit and verbal precision are deployed adroitly), Luis Buñuel (the amazing final scene) and Scandinavian modern exactness, Force Majeure thrills for its biting wit as well as its portrayal of how the smallest choice, the most seemingly minor gesture, can be as dramatically calamitous and emotionally revealing as pitched heights of drama.

14. Force Majeure, Ruben Östlund. A ticklish mix of Billy Wilder (visual wit and verbal precision are deployed adroitly), Luis Buñuel (the amazing final scene) and Scandinavian modern exactness, Force Majeure thrills for its biting wit as well as its portrayal of how the smallest choice, the most seemingly minor gesture, can be as dramatically calamitous and emotionally revealing as pitched heights of drama.

15. Mr. Turner, Mike Leigh. Leigh brings a longtime dream to supple fruition: a robust yet understated, unalloyed two-and-half-hour celebration of the boldly imagined, bracingly colored, late work of the great painter J.M.W. Turner, as well as his curmudgeonly disposition, captured by Timothy Spall in classic dudgeon.

15. Mr. Turner, Mike Leigh. Leigh brings a longtime dream to supple fruition: a robust yet understated, unalloyed two-and-half-hour celebration of the boldly imagined, bracingly colored, late work of the great painter J.M.W. Turner, as well as his curmudgeonly disposition, captured by Timothy Spall in classic dudgeon.

Read the full article »