Immigration has become such a hot-button topic in America, it’s almost impossible now to convince those who think everything is political that a drama about immigrants needn’t also takes sides. If a threat of deportation isn’t clear and present – or an uninvited guest in our country isn’t gorging himself on tax dollars — some critics simply will dismiss your movie as unrealistic or naïve.

Immigration has become such a hot-button topic in America, it’s almost impossible now to convince those who think everything is political that a drama about immigrants needn’t also takes sides. If a threat of deportation isn’t clear and present – or an uninvited guest in our country isn’t gorging himself on tax dollars — some critics simply will dismiss your movie as unrealistic or naïve.

This came as a surprise to Kenyan-born filmmaker Christopher Zalla, whose debut feature, Sangre de Mi Sangre (Blood of My Blood) won the 2007 Grand Jury Prize at Sundance and was nominated for a Goya as Best Spanish Language Foreign Film

“I didn’t intend to make a statement on immigration … the political debate wasn’t even on my radar when I began writing the screenplay,” insisted the 33-year-old Zalla, who spent his formative years in various African and South American countries. “I wanted to make a movie about how immigrants live in New York. Naturally, for these people, there’s always a threat of deportation, but it wasn’t a motivating factor for the characters … it merely raised the stakes for the audience.”

As Sangre de Mi Sangre (a.k.a. “Padre Nuestro”) opens, Juan, a grifter in his late teens, is running through the streets of a generic border town, where the fence isn’t very formidable. After making the leap across the border with several other youths – as did a half-dozen real illegals during the shoot — June takes refuge in the trailer of an 18-wheeler about to hit the road for New York.

Inside the trailer, Juan (Armando Hernández) makes the acquaintance of another border hopper, Pedro (Jorge Adrián Espíndola), en route to Brooklyn to reunite with the father he barely knows. Near the end of the journey, Juan steals an envelope that contains information about the whereabouts of his companion’s father and a trinket given to him by his mother to convince the man of his identity.

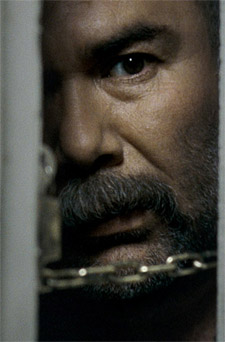

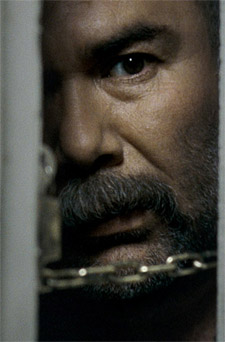

Cast adrift in the big city with no money and only the vaguest recollection of an address, Pedro struggles simply to survive from one day to the next. Meanwhile, Juan makes contact with the distrustful older man, Diego (Jesús Ochoa), a career dishwasher who is unable to see through the ruse.

While Diego is away at work, Juan spends his time loafing around Brooklyn and sniffing out the treasure everyone back home thinks is hidden in the old man’s threadbare apartment. Pedro finds occasional work as a day laborer, but, after befriending a junkie hooker, Magda (Paola Mendoza), spends most of his time either looking for Diego or keeping his new girlfriend from killing herself.

As if having Pedro’s identity stolen weren’t punishment enough, Zalla finds numerous occasions for near-misses with Juan and Diego. Our optimism for a happy resolution builds as the concentric circles grow ever smaller. Having already witnessed Juan’s skill with a knife, so, too, does the tension.

The inevitable confrontation at the end includes theatrical elements that have endured since Shakespeare’s days. The possibility for tragedy is omnipresent, of course, but the mistaken-identity through-line – especially as Diego slowly grows to accept Juan as his son — yields several uproarious moments, as well. Zalla doesn’t tip his hand until the very end.

“Some critics say they saw what happens coming,” said Zalla, who honed his filmmaking skills at Columbia University. “But the audiences with whom I watched the movie all gave out a collective gasp that seemed to combine laughter, shock and relief.”

Several critics have argued that such plot devices make Sangre de Mi Sangre feel contrived and manipulative, and, therefore, aren’t in keeping with the indie spirit. Even of one buys that premise, though, would it be a bad thing? One can only endure so many small, personal dramas or comedies about dysfunctional families – such as those shown repeatedly at Sundance — before crying out for a narrative that is full of surprises, odd coincidences and compassion.

Shakespeare wrote plays that were built on such contrivances, and no one has held it against them. For better or worse, Hollywood hasn’t been reluctant to manipulate audiences, either. If a studio had taken a chance on Zalla’s screenplay, the young border-jumpers might have played by Diego Luna and Gael Garcia Bernal, Diego would have been far more buffoonish, and the movie might have ended with all three men being sworn in as American citizens.

Sangre de Mi Sangre was a big hit in Mexico, where the immigration issue is seen from a completely different perspective. They recognized the characters and their dilemmas, but were unburdened by politics. Then, too, box-office was enhanced by the presence of actors who had established themselves in telenovelas and other home-grown entertainments. Ochoa, who plays the bellicose father, has won several of Mexico’s top acting awards, and another prominent character is portrayed by Eugenio Derbez, one of the country’s most popular comedians.

“There are real differences between classical conventions and those of Hollywood and indies,” said Zalla. “I wanted this movie to be about New York and about fathers and sons tearing down walls, and people who experience profound transformations in life. I didn’t have to make a big statement on immigration, because it’s already understood that there wouldn’t be a movie if Pedro simply could have gone to cops to ask for help.”

In fact, all immigrant groups have faced similar problems and enjoyed certain advantages by choosing to stay in New York, instead of Chicago, Iowa or Los Angeles. The characters could easily have been Dominicans, Nigerians, Chinese or Bosnian. Their stories would be the same.

“I decided on Mexicans because I’m fluent in Spanish,” Zalla explained. “They comprise one of the youngest immigrant groups in New York, but can be found working in restaurants all over New York.”

Zalla says he began working on the screenplay immediately after the attacks of 9/11. In addition to witnessing the horror and its lingering aftermath first-hand, he saw the true fiber of New York and its residents.

“New York represents hope for rest of the world,” he said. “There’s nowhere else that people from so many different places live together peacefully and in such close proximity.”

May 23, 2008

– Gary Dretzka

Immigration has become such a hot-button topic in America, it’s almost impossible now to convince those who think everything is political that a drama about immigrants needn’t also takes sides. If a threat of deportation isn’t clear and present – or an uninvited guest in our country isn’t gorging himself on tax dollars — some critics simply will dismiss your movie as unrealistic or naïve.

Immigration has become such a hot-button topic in America, it’s almost impossible now to convince those who think everything is political that a drama about immigrants needn’t also takes sides. If a threat of deportation isn’t clear and present – or an uninvited guest in our country isn’t gorging himself on tax dollars — some critics simply will dismiss your movie as unrealistic or naïve.