GONE GIRL (Three and a Half Stars)

U.S.: David Fincher, 2014

I. The Two Sides of the Story

Murder and murder mysteries are sometimes a game. A game for two.

Nick and Amy Dunne, the unhappily married couple trapped at the dark heart of the classy new movie thriller Gone Girl, are a pretty/witty movie pair who lost their jobs in the New York City magazine world thanks to the recession and the Internet — and then lost New York City when Nick’s mother was stricken with cancer, and the couple wound up in Flyover country (Nick’s old home town of North Carthage, Missouri). There, things begin to disintegrate. Nick cares for his mom, and opens a bar with Amy’s trust fund money, and the two of them, despite all good intentions (including the ones that pave the road to Hell), have been sliding ever since inexorably into a no-exit swamp of small town alienation, funk, and disaffection.

Now — courtesy of the bone-chilling narrative skills of novelist-screenwriter Gillian Flynn (who wrote the original novel of “Gone Girl”) and filmmaker David Fincher (who directed the movie from Flynn’s script) — the Dunnes are about to make a double entry into a Hell marked “His” and “Hers” Amy disappears. And Nick will soon be the prime suspect in what may have been her murder.

Even if you’ve never read the book or seen the movie (which may well be the case), you probably think you sort of know what’s going to happen next. But you probably don’t. Gone Girl, which Flynn has cunningly imagined and craftily, stunningly written, and which Fincher has visualized with all the eerie expertise that usually marks his high-style crime movies (including Fight Club, Se7en, The Game, Zodiac, Panic Room, and even The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo), is, like many another thriller of its type, dependent on how far we’re willing to suspend disbelief. But, in the realms of bestseller-turned-moviedom, Gone Girl is a cut or two above and definitely better than most — full of not always guessable tricks and twists, told in a tense, taut, racy, mostly engrossing style and boasting a lot of tangy, sharply drawn characters, very well played by a very good cast.

True, the central plot — much more complex than most books of this type — falls apart when you examine it afterwards. But then so, in a way, do most of mystery queen Agatha Christie’s triple-reverse doozies, like “The Murder of Roger Ackroyd“ or “Crooked House” or “And Then There Were None“ — at least if you try to reconcile them with something like the real world. While we’re reading Flynn’s book, or Christie’s, or some other murder mystery puzzle-plotmeister‘s, we tend to accept all these whoppers and implausibilities (exactly what tougher, more realistic writers like Chandler and Hammett tried to rescue crime and mystery writing from) because we want to immerse ourselves, temporarily at least, in the self-contained mystery-story puzzle-plot worlds the author creates. We want to play with her/him the narrative games and follow the rules she or he sets up — which is pretty much what happens here. Flynn’s impressively convoluted plot may not be too believable, but it doesn’t really have to be.

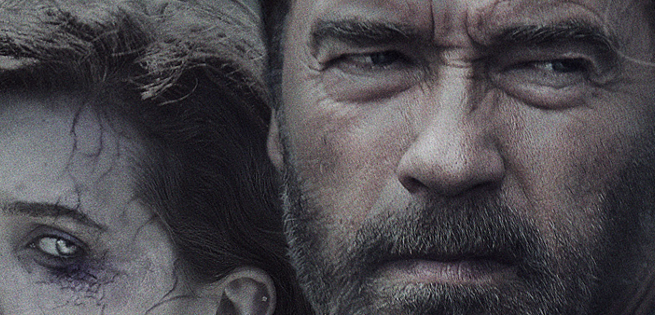

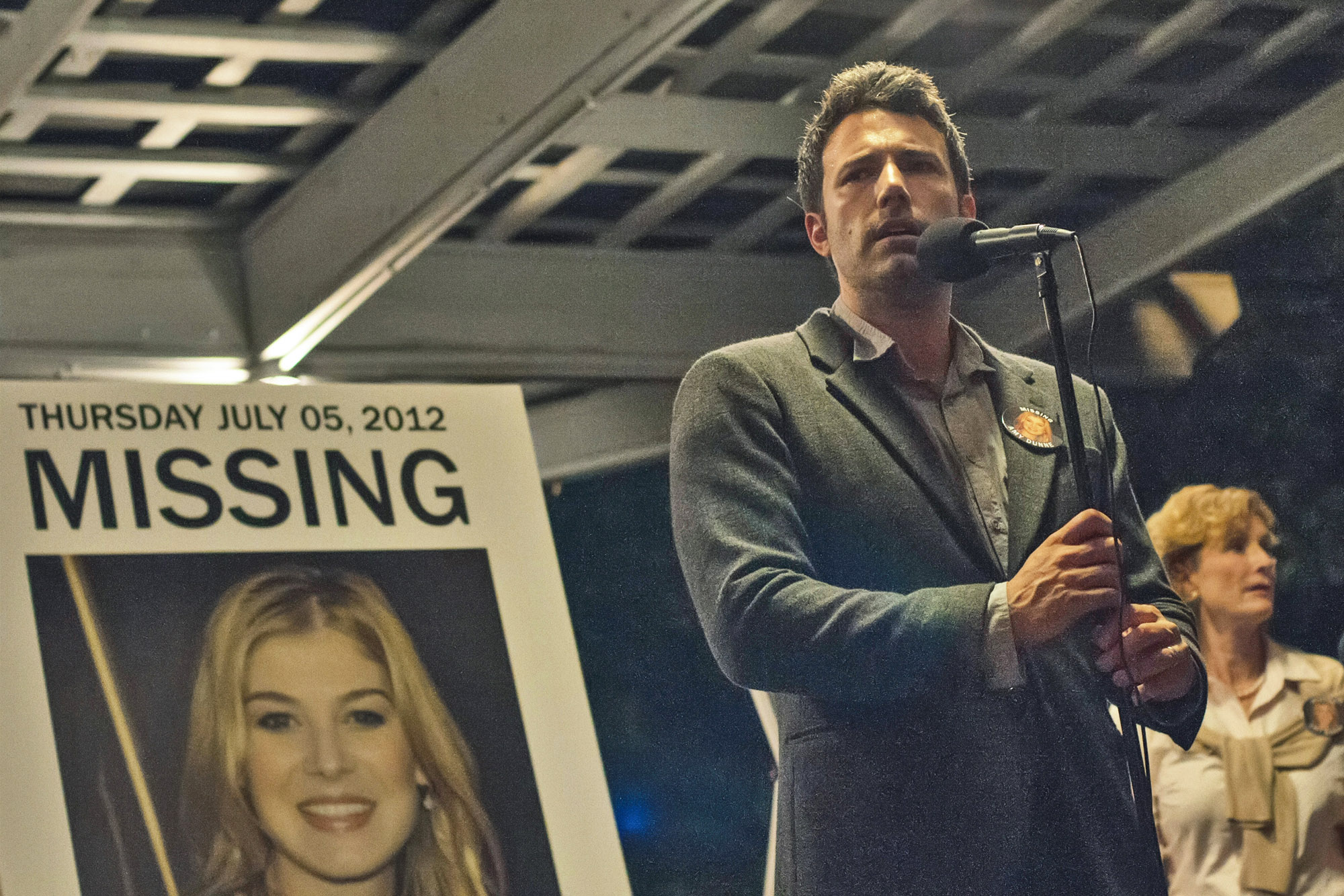

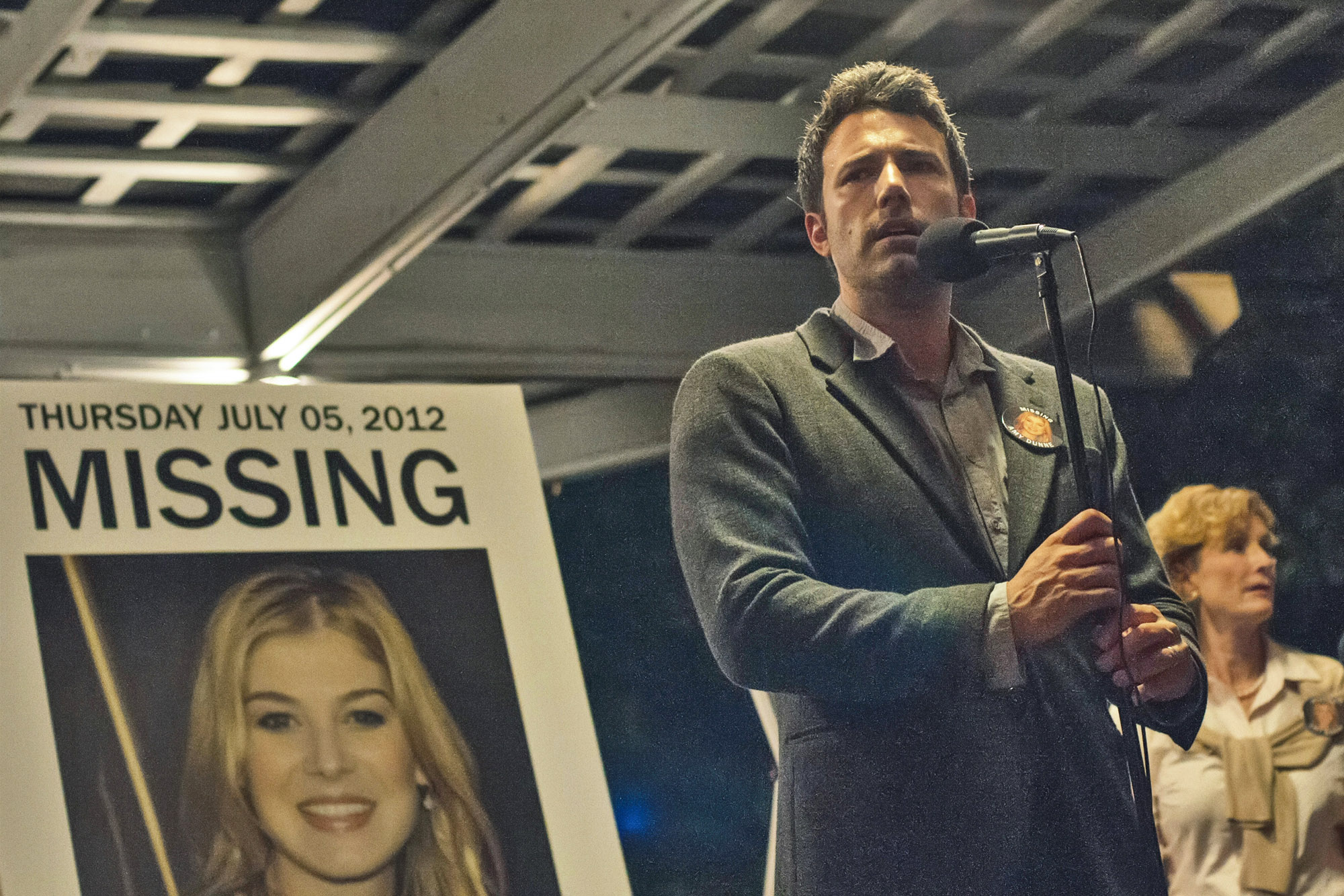

So, we start the ride on the morning of Nick and Amy’s fifth wedding anniversary, which they always celebrate with games and a treasure hunt, and Amy (played prettily and enigmatically by Rosamund Pike) is suddenly gone. And Nick (played with ambivalence and sharp skill by Ben Affleck) ruminates oddly about opening up his wife’s skull, and then reacts oddly to her disappearance, as if all the scenes he finds of a struggle, violence and possible abduction in their home were not the troubling tell-tales they seem to us. Eventually, he calls his best friend and twin sister Margo a.k.a. “Go” (played about as well as she could possibly be played by Carrie Coon), and he welcomes the police, represented by a keen-eyed, unbullable lady cop, Detective Rhonda Boney (played terrifically well by Kim Dickens) and her skeptical fellow officer Jim Gilpin (played discreetly by Patrick Fugit of the Cameron Crowe rock nostalgia classic Almost Famous).

Investigating the disappearance, these latter two keep unearthing clue after clue, most of which — almost all of which — point straight at Nick. The unemotional hubby, we soon see, is in big trouble. There are some messy complications and motive-suppliers, including part-time teacher Nick’s secret affair with his student-turned-mistress, the aptly-named small town doll Andie Hardy (Emily Ratajkowski); a self-confident sexpot with whom he has been sleeping for over a year. And there’s a big fat valuable life insurance policy payable on Amy’s death, or proof of death.

We get all this predominantly from Nick’s viewpoint, as his world crumbles around him. But, from the very beginning, the story is proceeding on two tracks: Hers — or what we learn from a diary that Amy wrote, dating back to their original courtship and describing how they met, wooed, and how the marriage fell apart. And His: telling the story from the present, beginning with Amy’s disappearance, and describing how Nick quickly becomes Suspect Number One and the tabloid demon hubby of the entertainment-crazed news media. Finally, the two tracks merge, and this tale of a messed-up marriage and a maybe murder races to its shocking climax.

And its even more shocking middle. Gone Girl’s now famous mid-novel switcheroo plunges us, at least for the rest of this review, into the limbo-land of Spoiler Alert. It doesn’t necessarily hurt to know what’s going to happen (as many of you now undoubtedly do). But for those who like to be tricked and teased and kerplopped into Shocksville as you watch a thriller, here‘s where you bail out. Happy landings.

SPOILER ALERT

II. Til’ Death Do Us Part, Dude

Now, as for me, I read the book before I saw the movie, so I knew all the film’s surprises before they happened. Yet I enjoyed the show anyway That’s largely due to all those sharply drawn characters and all those highly talented actors — and all the ways they become enmeshed in Flynn’s implausible but engrossing plot-web and Fincher‘s eye-catching cinematic horror-maze. It’s also due to the fact that this is, thanks to Fate and Flynn and David Fincher, a movie about and intended for adults, and not primarily targeted at wish-fulfilling teens and the big, largely Asian foreign audience. The fact that the movie comes from a successful, well-written novel (and one that’s been adapted by the novelist herself) helps the story keep its tight structure, as does the fact that Fincher respects his writer, Flynn, and doesn’t fool around over-much with her plot.

Anyway… That seeming dream couple Nick and Amy, as we learn from the two sides of the story, in truth have a horrible marriage and a horrific conjugation — yet why and what makes it a horror story aren’t all that obvious at first. As Nick’s nightmare grows, and as we keep getting Amy’s increasingly disturbing side of the story, we‘re torn giddily between the two. It’s hard not to feel sympathy of a sort for both of them at times, hard also not to be repelled by what has happened to them — the destruction of that champagne-fizzy rom-commy wooing and joking and coupling we see in Amy’s New York City diary scenes, and what happened, according to Amy (and what Nick confesses to), before the beginning of her vanishing, and Nick‘s nightmare.

Flynn juggles the dual perspective and the fractured chronology deftly, and Fincher keeps it all cold and focused and as sharp and smooth as ice on Scotch. One of the book‘s attractions — it’s also a kind of red herring — is the author’s amusingly cynical, inside look at the media world to which she used to belong. (Flynn was once an Entertainment Weekly critic/writer, until, like Amy and Nick — or, for that matter, me — she was found expendable.) Because she knows what’s going on in that world, and because she apparently doesn’t owe too many favors, the writer is able to spin a nasty, funny web to entrap Nick and then torment him — leaving him up shit creek with the lame-sounding explanation that Amy may have been kidnapped and/or killed by some old, vengeful boyfriend and that someone is framing him.

Soon, in Nick’s side of the story, Amy’s parents show up — Rand and MaryBeth Elliot (David Clennon and Lisa Banes), psychologist authors who used their daughter as the model for their amazingly popular “Amazing Amy” series of inspirational story-books for young girls and later, young adults. Also, helping or messing around in various ways, are nosy neighbor and Amy’s “best friend” Noelle (Casey Wilson), various media attackers or observers (Missi Pyle as TV’s Ellen Abbott, whom a lot of reviewers have compared to abrasive TV legal pundit Nancy Grace) or media pontificators (Sela Ward as the more Barbara Walters-ish Sharon Scheiber), and Taylor Bolt, a notorious defense lawyer, legendary for winning unwinnable cases (a part played brilliantly by, I swear to God, Tyler Perry.)

The smooth, cooler than cool, relentlessly savvy defense attorney Bolt, along with Margo, is probably the best-written role in both the book and the movie. And best played too. Perry, who often gets knocked by movie critics for the many showcase movies he writes, directs and stars in, is so good as this slick, knowing legal-gunslinger-for-hire — a part he plays to perfection — that this movie may have single-handedly rehabilitated his rep, at least among his usual non-constituency. Perry’s is not the only excellent performance in Gone Girl — Coon’s Margo and Dickens’ Detective Rhonda are almost as good and Affleck and Pike almost as good as them, and so is Lola Kirke as a raunchy motel pool gal and Scoot McNairy as a broken man from Amy‘s past. But Perry’s slick, shrewdly played turn is perhaps the most surprising and gratifying thing in the movie, especially if you only know him from a Madea dragfest or two.

The only major performance here that I couldn’t buy, in fact, was from the usually right-on Neil Patrick Harris, in the role of Amy‘s rich, mother-dominated, sexually fixated childhood beau, Desi Collings, a very unsympathetic if badly treated character (in the book), whom Harris, for some reason, has chosen to play at least partly (if not mostly) sympathetically. But it doesn’t work — at least for me. (He‘s culled some raves from other critics.) Desi, a creep and an obsessive chaser with a family bankroll behind him, is not the kind of guy movie audiences take a shine to, unless he’s played humorously, like Robert Walker in Strangers on a Train — an approach among several that the sometimes acidly funny Harris could certainly have used, and probably done very well.

Coon, as the good twin, and Dickens as the good cop, are probably the two most likable characters in the film, and both actresses are so good in these parts, that I think they together shoot down the suggestion from nay-sayers that both the movie and book are somehow anti-woman. Actually, Flynn has supplied her story with something in which most movies and most best-sellers are sadly deficient these days: a lot of well-written, well-played female characters, some sympathetic, some not, but most realized with psychological depth, smarts and sometimes salty wit.

The spur for those charges of misogyny — and the reason for that seemingly premature reader’s warning up above… (And are all you Spoiler Alert people, properly gone and honorably not reading this, or are a few of you still sneaking around, trying to pick up premature clues? For shame! Scoot!)…

SPOILER ALERT REPRISED (Again!!! We mean it.)

III. Vanishing Act

— as I was saying, the reasons for those misogyny indictments Fincher and Flynn have received, and the Spoiler Alert flag earlier on, is the fact, which we discover midway through, that Amy has not been killed by Nick, that she hasn’t in fact been killed at all, but that she’s staged everything, planted every anti-Nick clue including a phony pregnancy, faked the murder, composed a spurious diary, and that she’s now on the road, incognito and planning the ultimate coup de grace: a suicide that she will carefully disguise as a murder by Nick. All this is revealed about halfway through the story, when Amy’s Point-of-View segments stop being the faked diary and turn into a subjective narrative of what’s really happening to her. And maybe you needn’t worry overmuch if you ignored (twice!) those clearly marked Spoiler Alert signs I left up above, which you probably did. The industriously plotty Ms. Flynn has plenty more surprises left to spring after that, including an ending that may make susceptible males in her audience sort of queasy. (That’s probably part of why Flynn gives her book a fulsome, loving dedication to her husband.)

That double switcheroo at midpoint makes the roles of Nick and Amy, and the performances by Affleck and Pike, more complicated, and more admirably multi-layered, than they may first appear. They’re actually double roles, in which we see Amy as she is and as she’d like the world to perceive her, and Nick, who’s leading a double life of his own, as he is both really and not, and both of them as they are behind their masks or without them.

Affleck, a very solid actor, is very good here. He’s always been a classic likable leading man type, with a bracing touch of ego, and an actor who isn’t afraid — as Paul Newman wasn’t — to sacrifice some of that likeability and play partly-bad or fallible characters. So we keep following Nick and not totally condemning him, somewhat, even when it appears, as it does for much of the first part of the story, that he’s both a cheater and a wife-killer, and when we know that he’s been lying to Amy, and the world, and Margo, and the police, and everybody.

Affleck very carefully doesn’t use his leading man boyishly bemused killer smile overmuch in Gone Girl. In fact, up until the scene where he’s hornswoggled into posing with a pushy, flirty media-troller (Kathleen Rose Perkins) for a “selfie” that will wind up in the tabloids, I can barely recall him smiling at all, even when he‘s courting Amy. (Of course, the New York Nick isn‘t Nick at all, but the “Nick“ Amy has created to lynch him.) Rather strangely, Nick isn’t shown, at least enough for me to remember, with any or many close male friends (though this may have been just the time for his old buddy Matt Damon to show up for a little cameo, perhaps as a sharp-talking local bartender.) Instead, Taylor Bolt becomes something like Nick’s best buddy for the movie, or something close to it. Affleck makes that believable too, or somewhat believable:

What Nick is ultimately, is a smart, macho-looking guy, surrounded by women who are sometimes smarter or more macho than him — a somewhat talented but largely mediocre dude who has gotten by on his above-average smarts and looks and isn’t really in his brainy wife’s league, except perhaps as a better, less maniacal person.

What Amy is is a monster. All those years of being the human model for a beloved storybook character, her parents’ “Amazing Amy,” mixed with her disappointment with Nick and her rage at his infidelity, have seemingly stripped the real live Amy (she thinks) of any obligation to be real, or humane, or truthful, or good, or to consider any of the people around her as anything but gulls or suckers or schnooks. She accepted Nick as the charming, smart, good-looking guy that he, not completely accurately, purported to be. Then — when she was betrayed by Nick (who latched on to another, younger version of the “cool girl” Amy pretended to be to hook him), and by her parents (who got into s financial fix, reneged and took back her trust fund), and by the bigwigs who screwed up the economy, killed their jobs, and sent them back to North Carthage — she fought back. Viciously. Horrendously.

Pike, a Britisher with an interesting resume ( The World’s End, An Education, the James Bond movie Die Another Day, and Jane in the more recent film of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice), plays this scary, double-edged role with a gleaming, quiet, girlishness and opacity that keeps what she thinks mostly hidden. Pike’s Amy is like Tom Ripley in the films made from Patricia Highsmith’s “The Talented Mr. Ripley” by directors Rene Clement and Anthony Minghella: a psychopath with many masks playing such a complex deadly game that no one (or actually, almost no one) can keep up with her. (Minghella’s Ripley, by the way, was played by Matt Damon.) Pike gives the movie everything that the role needs, and I hope she and her admirers won’t take it amiss if I say that, good as she was, I would have liked to see Amy Adams in the part. Actually, I’d like to see Amy Adams in almost any part, including Franklin Delano Roosevelt or Tarzan.

IV. I Love you, I Hate You, Get Out of My Life

David Fincher makes tense, often ingenious, finely crafted, extremely good-looking movies that are full of psychological kinks and quirks, and that unroll with the dark inevitability of a death sentence into the well-organized nightmares that often entrap his characters. I wouldn’t necessarily call him a highly personal director or an auteur (in the French sense), except that there are certain kinds of stories he likes to tell and he has some unmistakable stylistic signatures, such as his cool palette, his classical editing, his brilliant shock tactics and his propensity for tales of people on the edge, serial killers and media types.

He’s a director with highly-honed skills and real cinematic bravura and bravado, as he demonstrates best in his masterpiece Fight Club. But he can also tell someone else’s story in a workmanlike, highly professional, almost self-effacing way, as he does here. Gone Girl is not really among his best. (That would be Fight Club or Zodiac or The Social Network), or his worst (Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, I suppose, though I rather liked it — even though I read Steig Larsson’s book first, and then saw the Swedish movie, and so it too didn’t have one damned surprise left for me, except the fact that they cast Rooney Mara in the title role instead of Noomi Rapace.)

Anyway, he did a good, sometimes great job again, here. Movies are sometimes at their best, when they aren’t necessarily personal (for the director) but when they bring together a highly gifted ensemble under the hand of a highly talented filmmaker, and when everyone gives their best to a good, or better than good, piece of material, as John Huston or Sidney Lumet almost always did. Gone Girl is no masterpiece. But it’s a good movie, well done on almost every level, a good story well-told (even if it‘s implausible), a good damned nightmare enveloping you in fear and loathing and shredded nerves and chaos and the dark. It squeezes every drop of juice, or every drop of poison, out of its plot. It rocks, at least part of the time. It also has a message. Don’t be fooled by appearances — or disappearances. And remember your wife’s anniversary.

END OF SPOILER (I SWEAR)